Good Morning POU!

Inexorably as whites fled Harlem during the early 1900s, blacks took over street after street, fanning out in all directions. On the one hand, the move into Harlem appeared to finally answer the black quest for a stable, unified neighborhood. One that both Philip Payton and John Nail had envisioned.

But the growth of black Harlem coincided with another massive wave of European immigrants coming into the city, this time from the Mediterranean region. By the turn of the century, only 20,395 black males were gainfully employed, a mere 18 for every 1,000 blacks in the city. As one black businessman wrote, immigrants “occupy every industry that was confessedly the Negroes”.

Italians, Sicilians and Greeks “have the bootblack stands, the newsstands, barber shops, waiters situations, restaurants, janitorships, catering business, steamboat work and other situations once occupied by Negroes.” Blacks had become an even less significant factor in New York’s economic life.

The influx of blacks into Harlem combined with the lack of work, exorbitant rents that landlords realized they could charge along with the negligence of providing repairs and services, along with the congestion, all contributed to an incredible death rate among New York City’s Harlem blacks at this time: 28.9 for every 1,000 – twice that of the white death rate.

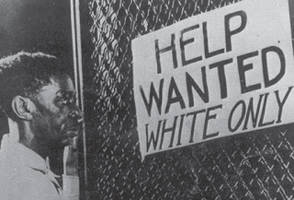

Nevertheless, Harlem continued to be a magnet for blacks from the Carolinas, Georgia and Virginia. Harlem’s attraction reached a feverish pitch during World War I. Because of the war, the massive European emigration to America came to an abrupt halt and seemed to foreshadow increased job opportunities for blacks. But whites worked hard to keep black Harlemites confined to the bottom.

Entering an apartment house, it was not unusual to find that the “indoor aviator” – the elevator operator – had a doctorate. It was a common thing, a Ph.D. who couldn’t get work. All Americans were experiencing a job crisis in the 1930s, but in Harlem the problem was exacerbated by continuing large scale discrimination. The traffic manager of the New York Telephone Company freely acknowledged that none of Manhattan’s 4500 operators were black. Similarly, the New York Edison Company had 10,000 workers, but only 65 were black, all of them worked as porters, cleaners and hall men. The same was true of the Consolidated Gas Company, only 213 of its 10,000 workers were black, and all of them were porters. Among the 10,000 employees of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company, 580 black messengers, subway porters and cleaners.

Oddly enough, as blacks moved in, another fantasy took hold, prompted by fanciful, optimistic and erroneous estimates made by blacks themselves. They believed they owned virtually all of Negro Harlem; that 3/4s of the area’s real estate was in black hands. As a result, blacks got the impression that they controlled their own community. In truth, blacks owned less than 20% of Harlem’s businesses. As reality surfaced, Harlemites became increasingly frustrated at the lack of employment opportunities in white owned stores and businesses…and Harlem was becoming a vast slum. There was the crowding, families struggling to make ends meet, despair over lack of opportunity and the daily obsession with playing the numbers game hoping to strike it rich.

.jpg)

It bothered Harlemites that few blacks owned the stores they patronized. Of 12,000 retail stores operating in Harlem in 1930, only 391 were owned by blacks and 172 of them were grocery stores. There was one black owned cinema, and 75 black owned saloons. Otherwise, black enterprises were limited to small grocers, insurance agencies, hair salons and funeral parlors. One writer cynically quipped that “the only businesses which are left to the Negro are pruning himself and burying himself”. There was however, one flourishing industry that was unlisted: the numbers game, which whites called “the nigger pool” or “nigger pennies.”

On the other hand, the 1920s was also the era of the Harlem Renaissance, when writers and poets such as Claude McKay, Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes gave blacks throughout the United States a sense of their history and traditions and voiced their yearnings. The Negro, as Hughes put it, “was in vogue.” These writers, as well as artists and photographers of the Renaissance, concerned themselves with esthetic and cultural matters rather than political goals. Those were left to militant black nationalists such as Marcus Garvey who, exasperated by the inequalities, advocated black independence. Black pride and self-reliance became catchwords.

The 1920s were also the Jazz Age and jazz reigned supreme in Harlem. By day, Harlem was a poor working person’s community, but at night it was a playground for whites, or in the words of Collier’s magazine, “a national synonym for naughtiness” and “a jungle of jazz.” White men and women cabbed up to see the lavish shows at nightclubs such as the Cotton Club, where blacks were barred and the only ones to be seen on the premises were either in the chorus line or the band.

By 1930 and the start of the Depression, when whites started to decline in “slumming” in Harlem, the Renaissance had run its course. Appraising it realistically, Langston Hughes said “All of us knew that the gay and sparkling life, was not so gay and sparkling beneath the surface.” Hughes acknowledged that he had had a “swell time while it lasted. But I thought it wouldn’t last long. For how long could a large and enthusiastic number of people be crazy about Negroes forever?” Besides which he added, “ordinary blacks hadn’t heard of the Negro Renaissance. And if they had, it hadn’t raised their wages any.”

There was one event that could tie together the class divisions of Harlem – north of Seventh Avenue “The Great Black Way.” There, on a Sunday, the Harlemite, whether well off or poverty stricken, uneducated or classically trained, promenaded. Promenaded, not walked, as James Weldon Johnson put it. A promenade was an adventure:

One puts on one’s best clothes and fares forth to pass the time pleasantly with friends and acquaintances and, most important of all, the strangers he is sure of meeting. One saunters along, he hails this one, exchanges a word or two with that one, stops for a short chat with the other one. He takes part in the joking, the small talk and gossip, is introduced to two or three pretty girls, who have just come to Harlem.

Early 20th century Harlem was indeed a study in contrasts. The bubbling night life, with music filtering into the avenues where cabs carried zoot-suited hipsters, differed sharply from the humdrum daily life of most of its citizens. The wide, open-sky vistas were marred by the silhouettes of rundown tenements. And for every beaming smile and burst of laughter, there were a dozen frowns. To live in Harlem was to navigate between joy and pain.

To Walker Smith, who was born and raised in the 1920s in rural West Virginia, where Jim Crow rules, Harlem was a place where he could feel “comfortable,”.

The sight of a police officer named Lacy “a big black giant” who directed traffic at the intersection of 125th Street and 7th Avenue, “making white folks stop and go at his bidding” was symbolic of the sense of empowerment blacks experienced in Harlem, however small. Many residents had come from places where “there was no black authority or authoritative figures who commanded respect.”

For those born and bred in Harlem, there was even a feeling of superiority. Foster Palmer was “led to think that we were special because we came from New York – superior to everybody else.”

To those who lived there, Harlem was ultimately, a state of mind.