Good Morning POU!

This week, as we head into the most revered horse race in the USA, The Kentucky Derby, we will feature African Americans who are lost legends in the world of thoroughbred racing – not only jockeys, but trainers and grooms as well.

(You can also check out our previous week long feature on The History of Black Jockeys from 2013 – just search “Black Jockeys” on the site’s search function).

The names and stories of the men and women who were primary caregivers to thoroughbreds, whether great champions or hard-working horses who ran on local racetracks, are largely unknown. Since many of these people were perceived as menial workers employed in the stables of the wealthy, they were overlooked by turf writers and the general public. However, even though fragmentary, a few stories of thoroughbreds and the men who loved them have come down to us from the past.

One such narrative fragment concerns Will Harbut and the legendary Man O’ War.

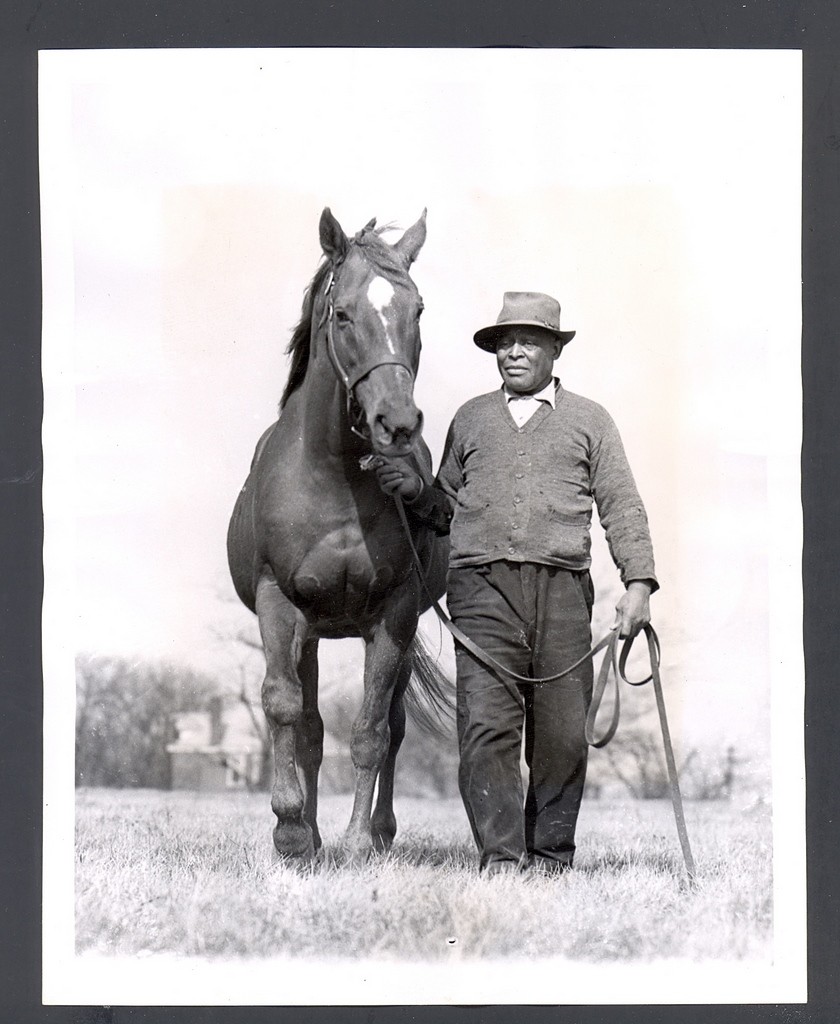

Will Harbut

The thoroughbred Man O’ War is considered by every expert and every racing aficionado as THE greatest thoroughbred ever in the history of horse racing. Written accolades of this Triple Crown winner inevitably will list the owner, trainer and jockey, and after retiring to stud, his breeder, but it may surprise you to learn that the closest person to the legendary horse was his groom.

A groom or stable boy is a person who is responsible for some or all aspects of the management of horses. The term most often refers to a person who is the employee of a stable owner. The groom is the person who provides daily care for these horses, everything from cleaning out the four stalls, to leading the horse over to the races on race day. While the groom is often thought of as a menial position, the relationship born between Will Habut and Man O’ War was so significant, that according to Man O’War’s owner, Samuel Riddle, the horse simply refused to allow anyone to handle him except Harbut.

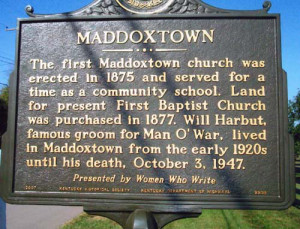

Will Harbut was born in 1885 and as a young man, moved to Maddoxtown, where he built one of its first houses on the land he purchased. Maddoxtown was one of many “free towns” that sprung up in Kentucky after the Civil War where freed men and women could settle, farm and raise their families.

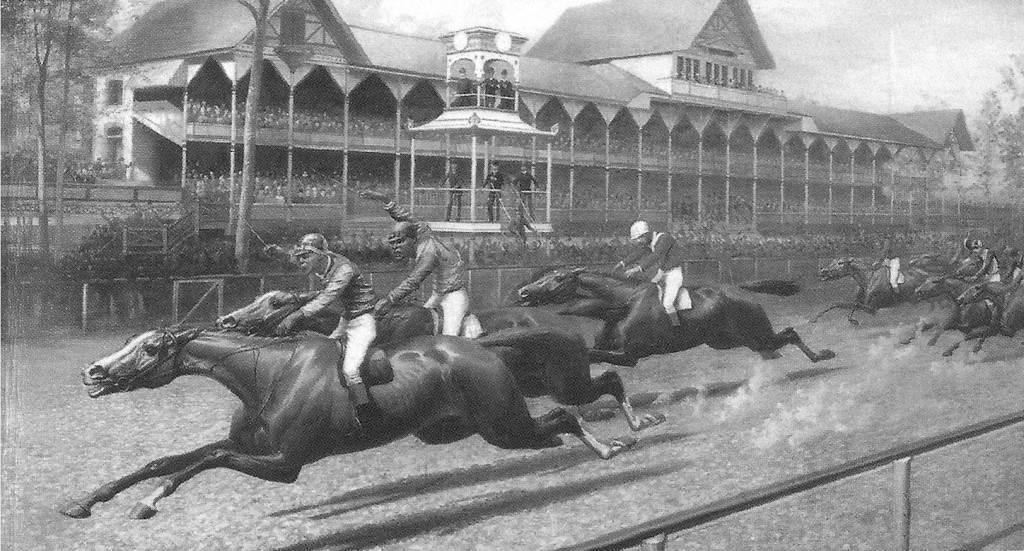

The residents of Maddoxtown also worked on the horse farms of the Bluegrass. As such, they were simply continuing a tradition of long-standing, since African American men had cared for and ridden Kentucky thoroughbreds during the slavery era. Their contribution to thoroughbred history had been essential to its very existence: 12 of the 15 jockeys who rode in the very first Kentucky Derby were African-Americans and thoroughbreds carrying African-American riders would wear the roses 15 times over the next 28 years. Men from the free towns around Lexington also served as trainers, as well as grooms, passing on their thoroughbred expertise from father-to-son.

Will Harbut’s Maddoxtown home, where he and his wife, Mary, raised their 12 children, faced out onto the rolling pastures of the world’s thoroughbred heartland. On any given morning, Will could stand on his porch and watch bands of thoroughbreds grazing and rollicking in the lush bluegrass. By the time he was hired by farm manager Harry Scott, Will Harbut had already gotten the reputation for being a fine horseman and, some said, a horse whisperer. And when Scott was asked to run the operations at Faraway Farm in 1930, he took Will with him.

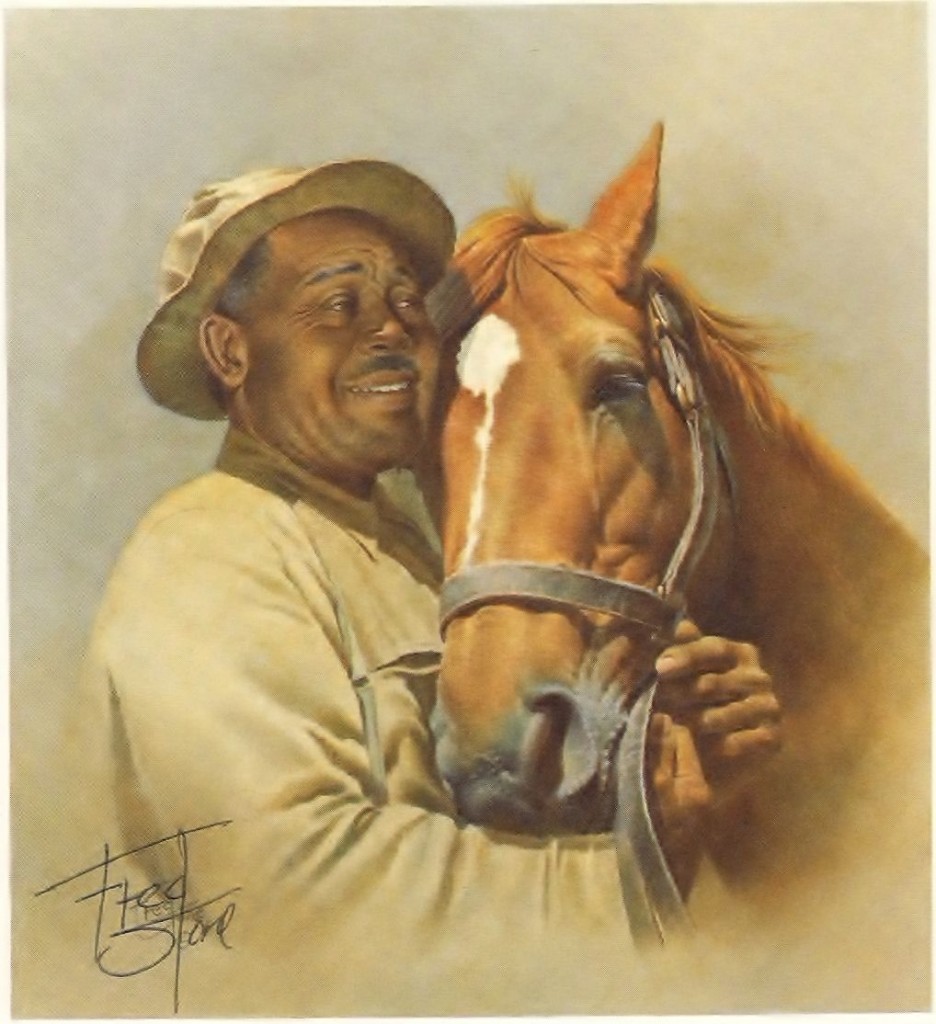

Will Harbut had a rich, melodic voice and wide, smooth hands. According to Will’s son, Tom Harbut, it wasn’t long before his father and Man O’ War became as one. Of his father, Tom had this to say when interviewed by D. Cameron Lawrence for an article published in the October 2006 issue of Kentucky Humanities, ” He was well respected and I admired him for his accomplishments because for one thing, he was closer to the slave era. At that time, he wasn’t allowed to read or write. And to get where he did was amazing.”

Will was Man O’ War’s everything, the first face he saw in the morning and the last he saw at night. Will fed him, bathed him, mucked out his stall, groomed him, hand-walked him, brought him water and turned him out into his paddock. It was Will who brought him to the breeding shed or led him out to meet the steady stream of admirers who came to visit. And it was Will who reminded him to be gentle with the children that brought him a carrot or a lump of sugar and Will who admonished him to behave himself, which he did by snapping the shank and demanding, “Stand still, Red” or “Stop fidgeting, Red” or “Stop messin’ around, Red.”

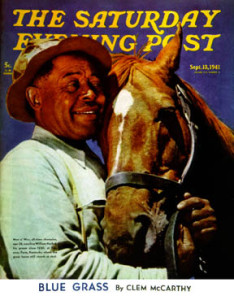

Having a best friend like Will Harbut also assured the champion some privacy and respect. Samuel Riddle was most generous in allowing fans access to Man O’ War, for Faraway Farm was open to visitors every day from 9 a.m. – 4 p.m. Although he greeted over a million visitors, Will refused to wake the stallion up if visitors arrived when the horse was napping, telling them rather curtly, ” When Man O’ War wants to get up, he get up. And when he wants to lie down, he lie down.” If it was time for Man O’ War to be fed, Will would shoo people away and ask them to wait. If the stallion was out in his paddock and if Red appeared to be inviting company, Will might take one or two people right up to him. Although dignitaries from all walks of life, including film star Jeanette MacDonald, Henry M. Leland (founder of Cadillac Co.), Lord Halifax and government officials visited on a regular basis, Will never distinguished between famous and average folks. Everyone was treated with the same respect and everyone was made to understand that the only dignitary at Faraway was Man O’ War himself.

In Dorothy Ours’ book Man o’ War: A Legend Like Lightning, Ours writes about the visit from Lord Halifax of Britain, who never took his eyes off the groom “who was unrolling the long glories of Man o’ War and his sons and daughters … like Tennyson on the passing on King Arthur.”

That, Lord Halifax was reported to have said, “was worth coming halfway ’round the world to hear.”

Tom smiles at this. Still, pictures of the stern father Tom knew and the horse he loved still hold high hallowed places in Tom’s life.

His father had come up from nothing, says Tom, and had made so much of himself. He had a certain pride which he instilled in his children. That they could do what they set their minds to. That they were good enough. That God mattered and work mattered.

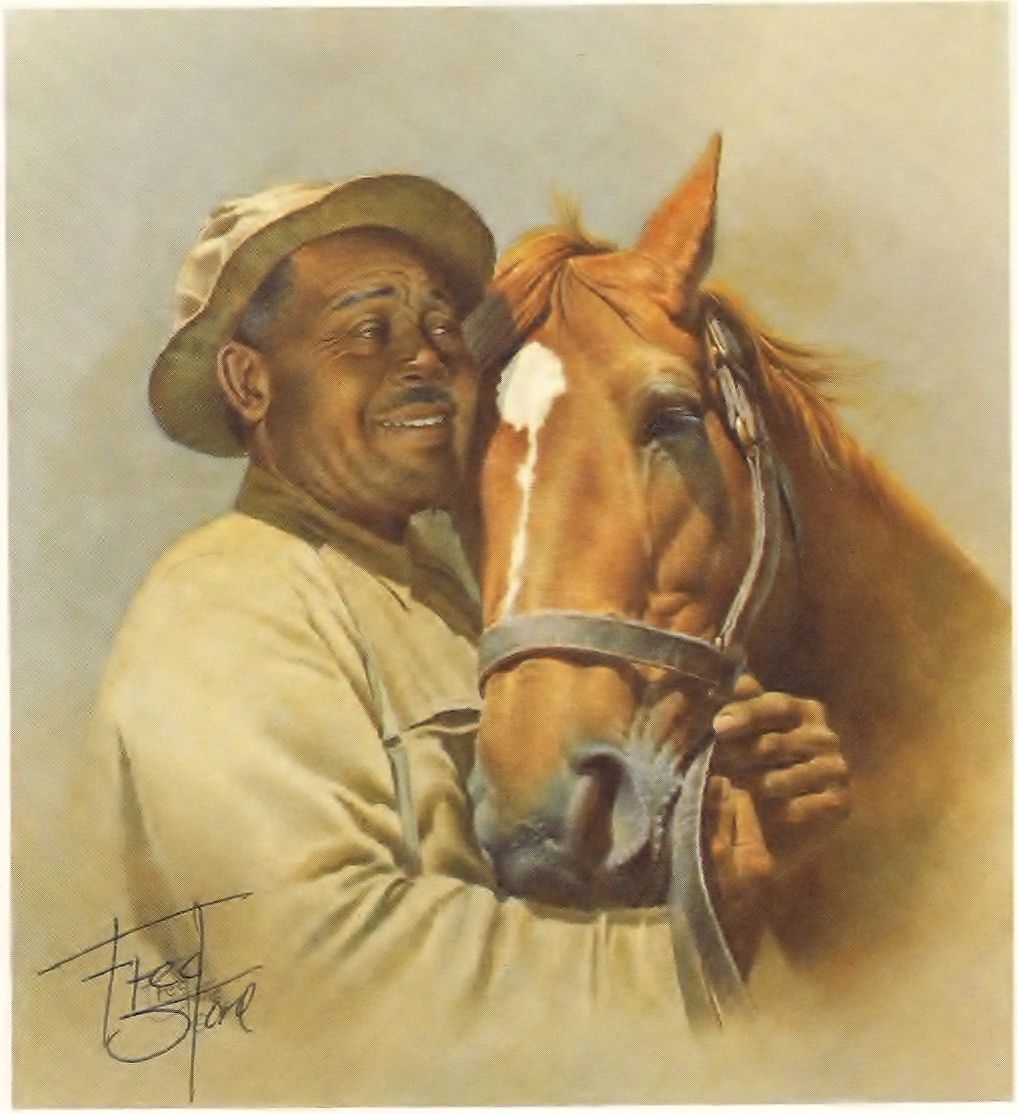

The famous cover shot would also inspire equine artist, Fred Stone, whose collectors’ plate, “Forever Friends” remains one of his most popular. The most famous photographers, artists and sculptors of the day immortalized the champion, who stood for sittings patiently because Will was almost always at his side.

Even though Man O’ War, unlike most thoroughbreds, found the love of his life after retirement, there came a day when Will did not come to Faraway Farm. In 1946, Red’s best friend was the victim of a stroke that left him partially paralyzed and blind. Joe Palmer, writing of Big Red’s upcoming birthday that year, began this way, “When Man O’ War celebrates his next birthday here the party will have already been spoiled. Will Harbut, the groom who tended the big red stallion for nearly 20 years, was stricken with an attack which has at least temporarily deprived him of his sight as well as his powers of motion.” He went on to say, talking about Will’s legendary stories of Man O’ War’s exploits, “…It was, indeed, a full-blown and well-flavored narrative, now apparently never to be told again, for Will’s chances of complete recovery seem slight…It has for years been a half-jesting comment in Lexington that neither Man O’ War nor Will Harbut would be able to live without the other, and the jest is now getting a little bitter…”

Palmer’s observations proved prophetic.

Will Harbut died on October 3, 1947. His obituary in The Blood Horse listed among his survivors his wife, six sons, three daughters and Man O’ War.

Less than a month later, as photographer James W. Sames recounted to The Blood-Horse, he visited Faraway Farm at the request of farm manager, Patrick O’Neill, to take some pictures of Man O’ War. Little did he know that the last photo he took, in color, would be the final image of a legend. When his new groom, Cunningham Graves, affectionately known as Bub, took Man O’ War back to his stall, the stallion balked. His head held high, he looked out and down the driveway, perhaps searching for a familiar figure. Finally, Man O’ War entered his stall at Faraway Farm and lay down.

He never got up again. Man o’ War died on 1 November 1947 at age 30 of an apparent heart attack, but observers say, was a broken heart.