This week we will take a look at the works of Ophelia Settle Egypt.

In the late 1920s, Ophelia Settle Egypt conducted some of the first and finest interviews with former slaves, setting the stage for the Works Progress Administration’s (WPA) massive project ten years later. Born Ophelia Settle in 1903, she was a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and a researcher for the black sociologist Charles Johnson at Fisk University in Nashville.

Over the course of her career Settle helped expose the infamous Tuskegee study of syphilis among black sharecroppers, and played a leading role in Charles Johnson’s “Shadow of the Plantation” study of the sharecropper system. As the Depression wore on, she left Fisk to assist with relief efforts in St. Louis. She accepted a scholarship from the National Association for the Prevention of Blindness to study medicine and sociology at Washington University, where, as a black woman, she was required to receive all her lessons from a tutor. She also became head of social services at a hospital in New Orleans, and five years later conducted research for James Weldon Johnson, about whom she wrote a children’s book. Egypt was a social worker in southeast Washington, D.C., and for eleven years was the director of the community’s first Planned Parenthood clinic, which was named for her in 1981.

Ophelia Settle Egypt died in Washington, D.C. in 1984. She was 81.

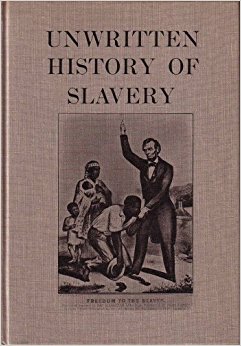

It was in the 1930s, that she helped Dr. Charles S. Johnson to interview 100 former slaves in West Tennessee. The research was the basis of the 1968 publication Unwritten History of Slavery: Autobiographical Accounts of Negro Ex-Slaves, as well as several articles. Her research would show that slaves were far more rebellious than previously known.

The following excerpt is also based on the research and is from an unpublished manuscript in the Ophelia Settle Egypt Papers at the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University:

In addition to the newspapers, biographies and autobiographies among which is the story of Harriet Tubman, the famous conductor of the Underground Railroad, there is an untapped source of unwritten history – the story of slavery as told by those who lived through it to experience the freedom about which many of them had dreamed. Most of these ex-slaves have now passed irrevocably into history, but they left behind a vivid picture of life in bondage as they remembered it. Granted that there is a high degree of subjectivity in the remembered material, there is historical value in seeing slavery through the eyes of the slave.

During l929-30, as a member of the Staff of the Social Science Institute at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, I interviewed more than l00 ex-slaves living for the most part in Tennessee and Kentucky. The oldest of these men and women had been exposed to slavery for 46 years while the youngest was only eight years old when the Civil War ended. Their intimate personal stories reveal attitudes and patterns of behavior about all aspects of plantation life. However, the area selected for emphasis here is that dealing with the slaves who refused to fit themselves into the role required of them.

This group of ex-slaves knew personally fifty slaves who “wouldn’t take a whippin.” Thirty-five of these ran away in protest, often after a fight with an overseer; nine fought back and succeeded in thrashing the overseer or master; three others killed the overseer and one slave pulled his pursuer into the river to drown with him. Another committed suicide by jumping into a vat of melting iron because he was about to be caught and whipped.

A woman who was about to be sold away from her two children because she “wouldn’t be whipped” killed her children and herself on the eve of the pending separation. Another woman threatened to commit suicide because she had been whipped severely; after climbing down into a well, she refused to let herself be drawn up until the master promised not to whip her again. One master warned his overseer not to attempt to whip a slave called Henry Halfacre. When he tried, Henry knocked him unconscious. He was sold but “they sneaked him back again when the overseer was changed.” In one case an overseer was killed in an unpremeditated group project, according to a Franklin, Tennessee ex-slave who at that time was old enough to be a regular field hand:

“I remember during slavery a bunch of slaves were piling leaves up and burning them, and the old overseer was standing with his back to the big fire with a big whip in his hand. Don’t you know they knocked him over in that fire and burned that old white man to death! Nobody never did know what happened to him; they just burnt him up.”