Good Morning POU!

Today’s feature comes to us from a 2011 column in the Lexington Herald-Leader.

Kentucky is hoping to add another thread to the increasingly colorful tapestry of the history of the state’s horse industry.

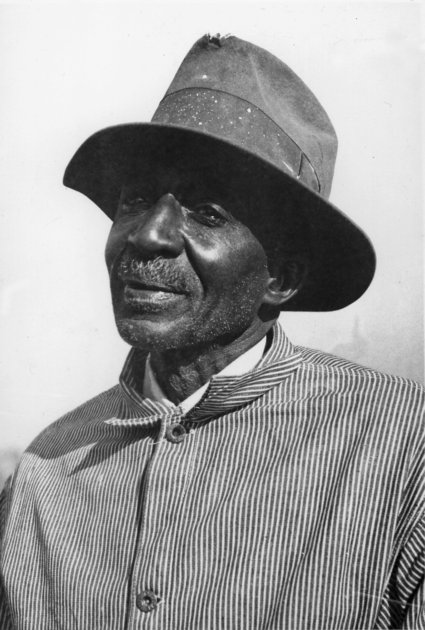

The state has applied to have a house at 547 Breckenridge Street added to the National Register of Historic Places because of its link to a largely forgotten African-American horse trainer named Courtney Mathews.

Mathews came onto the racing scene near the end of the Golden Era for black jockeys and horse trainers in America and raised a generation of equine greatness, including 1902 Kentucky Derby winner Alan-a-Dale, four Kentucky Oaks winners, and the 1912 American Horse of the Year, The Manager.

Mathews was born on a farm in Jessamine County in 1868. At 16, he went to work handling one of the major sires of the day, a stallion named Deceiver. Sandford C. Lyne imported Deceiver from England for breeding after the horse won a $20,000 purse at Epsom. At Larchmont Farm in Woodford County, Lyne soon entrusted his youngest son, Lucien, as well as his horses to Mathews.

According to a fascinating 1938 interview with Mathews in The Blood-Horse, he helped future jockey Lucien Lyne get his start riding ponies in Kentucky’s county fair circuit. Sandford Lyne also gave Mathews and young Lucien some Thoroughbreds to race.

After early successes under Mathews’ watchful eye, Lucien Lyne became a top American jockey, and then moved to England and Europe, where he went on to greater success. In 1907, Lyne rode for a season for Lord Carnarvon, who that same year hired an archaeologist named Howard Carter to further his hobby of exploring Egypt. (Together, Carter and Lord Carnarvon would discover King Tut’s tomb in 1922 in Egypt.)

In 1908, Lyne moved to Belgium and invited Mathews to come as well.

By that time, Mathews was working for Ashland Stud in Lexington breaking and training yearlings for Major Thomas Clay McDowell, Henry Clay’s great-grandson.

Mathews had become an acknowledged expert at prepping yearlings for prestigious auction sales, particularly at Saratoga Springs in New York every summer.

Eventually, by 1914, Mathews was persuaded. “Lucien had written me to come to Belgium,” Mathews said in the 1938 interview. “I had planned on going right after the sale of Major McDowell’s yearlings at Saratoga, and was going to cable Lucien from Saratoga.”

But World War I intervened. On June 28, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated in Sarajevo. And the world began to gear up for war.

On July 29, Lyne won the Ostend Derby riding for a Count Ribancourt; within days, the Germans invaded Belgium and Lyne swiftly sailed for home.

“When the war broke out, Lucien beat me back to Kentucky,” Mathews said.

After the war, Lyne went back to Europe to ride exclusively for King Alfonso of Spain but Mathews stayed in Lexington, where he had become a horseman of rare stature.

Return home boosts career

Mathews went to work for McDowell in 1897, when McDowell sent Mathews to Latonia in Covington to train and race a filly named Bracegirdle.

At the turn of the last century, Latonia was one of the top racetracks in the United States, drawing 100,000 spectators a year and top horses from around the world. At one time, winning the Latonia Derby was considered a more impressive feat than winning the Kentucky Derby at Churchill Downs in Louisville.

In going to Latonia, Mathews could have trained alongside other top black trainers and jockeys of the day, who were then as famous, if not more so, as any top professional athlete today.

But the most famous, Isaac Murphy, was not among them. Murphy had died in the winter of 1896 at his home in Lexington at age 34 or 35. Renowned in his time as the most honest of riders, Murphy had problems with weight and possibly alcohol that cut short his life and brilliant riding career. In his time, Murphy won the Latonia Derby five times and the Kentucky Derby three times.

In any event, Mathews’ time at Latonia was short: The 4-year-old Bracegirdle had bowed a tendon the year before and promptly re-injured her leg the first time she attempted a fast workout.

The pair came home to Ashland, where Bracegirdle would go on to foal several top racehorses. Mathews was assigned to break yearlings, and the first crop he handled included Rush, who went on to win the 1899 Kentucky Oaks.

Ashland had become an agricultural showplace and raised Thoroughbreds and Standardbreds for harness racing.

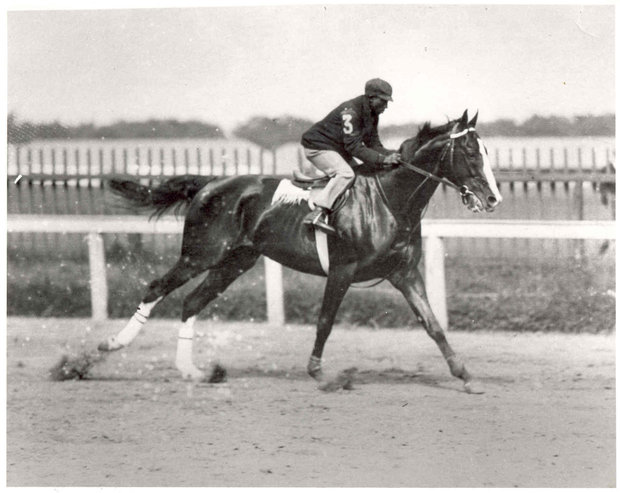

In 1900, Mathews was given a distinguished crop of yearlings to raise and prepare for racing. Among them was Bracegirdle’s first foal, The Rival, and another named Alan-a-Dale. Both horses were fast but Alan-a-Dale had troublesome legs and someone had the idea to train him while pulling a buggy or harness-racing sulky rather than with a rider up to preserve his legs. They would use a jockey only for timed trials.

Jimmy Winkfield on Alan-a-Dale

McDowell decided both homebred horses would represent Ashland in the Kentucky Derby in 1902. As the horses were being prepped, the great black rider Jimmy Winkfield rode them both in timed workouts to see how fast they were. Winkfield, who had won the Kentucky Derby the year before aboard His Eminence, thought Alan-a-Dale, a son of 1895 Derby winner Halma and a great-grandson of 1881 winner Hindoo, was the better horse and devised a strategy to ensure he would get to ride him in the big race.

For more than a month, Winkfield later said, he deliberately rode Alan-a-Dale slightly slower than The Rival. McDowell gave white jockey Nash Turner, a prominent rider from the Northeast, first pick and, going off the times, Turner chose The Rival.

Winkfield also knew that the racetrack at Churchill was covered with deep sand during the off-season that was scraped to the outside of the track during races.

During the Derby, which had only four runners that year, Winkfield would repeatedly maneuver the other horses to the outside and edge them out into the sand to slow them down. Alan-a-Dale went lame in the stretch but hung on to win anyway, and The Rival came in third.

McDowell reportedly gave the two jockeys $1,000 each for the race. It was Winkfield’s last Derby win; the next year he came in second and left for Russia, where he would enjoy unparalleled success until revolution forced him to flee.

Did he train Alan-a-Dale?

No records have been found of what Mathews earned but the house on Breckenridge Street indicates that he must have been paid well in his time. The house, built about 1905, is made of carved sandstone blocks and originally had a slate roof. None of the others in the neighborhood were so grand as the two-story edifice with its maple floors and double-sided fireplaces. It had at least five bedrooms upstairs and a grand double foyer.

In 1928, when Mathews and his wife, Louisa, bought the home with a $3,000 mortgage, there was only one other African-American family in the neighborhood.

There are other clues to Mathews’ stature, including the 1938 interview itself, which referred to him as “an expert horseman whose judgment of Thoroughbreds and knowledge of breeding and caring for horses is respected by all who know him.”

That interview includes a revealing incident in Mathews’ 38-year career at Ashland. At some point Mathews and McDowell had a disagreement over wages. Mathews left, and promptly returned to Larchmont Stud and “Pops” Lyne.

After a month and eight days, McDowell conceded, called for Mathews at Larchmont and rehired him. Mathews stayed with Ashland until shortly after McDowell’s death.

Years later, Mathews was magnanimous about it. “You can say this for me,” he said in 1938, “there never was a finer man ever lived than the Major. And he was a real horseman; knew how to train a horse, too.”

That leads to a curious question: Who really trained Alan-a-Dale?

The trainer of record listed by Churchill Downs is McDowell, and Ashland is proud that he is one of very few owner/breeder/trainers to win the Kentucky Derby. An illustration of the day shows McDowell in the sulky behind Alan-a-Dale. And, at one point, McDowell would train professionally for William Kissam Vanderbilt.

But the 1938 story, a look-back from a grand old man of the sport, reports that Mathews “broke and trained Alan-a-Dale, which won the Kentucky Derby in 1902.”

In the same paragraph, writer Brownie Leach wrote that Mathews gave “Woodlake, winner of the Latonia Derby, etc., his first lessons as a race horse. Other good racehorses that started out under his careful direction were The Manager, Lady Madcap, King’s Daughter, Ellen-a-Dale, Distinction, The Minute Man, Star Jasmine, St. Augustine, Waterblossom and Distinction.”

Such plaudits open the door for a much greater role for Mathews in the training of Ashland’s vaunted stable than just “overseer,” as a contemporary city directory lists him.

And the house that he bought in 1928 was just a block from the city’s racetrack, the Kentucky Association track that preceded Keeneland. Mathews would have been conveniently located to oversee horse training, particularly since by that time much of Ashland, beginning with what is now Hanover Avenue, had been developed and the farm no longer had its own training track. In fact, McDowell had moved his Thoroughbred breeding operation to Buck Pond Farm in Woodford County, where it would have made more sense for Mathews to be living instead of downtown Lexington.

Accomplishments difficult to verify

The historical record can be murky on the achievements of horsemen of color.

There certainly were plenty of prominent African-American trainers, including Edward Dudley “Brown Dick” Brown, who was born a slave, became a jockey (he won the 1870 Belmont aboard Kingfisher, who was trained by fellow black trainer Raleigh “Rolla” Colston) and then a Derby-winning trainer himself (he trained 1877 Kentucky Derby winner Baden-Baden).

But it also would not have been unheard of for an employee’s efforts to be downplayed in favor of a more famous farm owner, and in the early 1900s, there was no Kentucky blood bluer than that of Henry Clay’s descendants.

Leon Nichols, who is CEO of the Project to Preserve African-American Turf History, has found that restoring these men to their rightful place in history can take a lot of digging.

“Our whole point is to get the recognition they deserve,” Nichols said. He’s heard of Mathews but only of his association with Ashland.

Based on the evidence of the 1938 interview, Nichols surmises that Mathews would have been both highly skilled and well paid but filling in the blanks might be difficult.

“A lot of what they attained stayed within the African-American community,” Nichols said “They were highly respected in the community but they didn’t get much widespread recognition.”

In part, that’s what makes the 1938 interview so extraordinary. It shows that Mathews was an expert, with anecdotes and knowledge that a mainstream horse industry publication wanted to preserve.

It also tells that after McDowell’s death in 1935, Mathews went to work for Leslie Combs II’s Spendthrift Farm, where horses under his care were thriving.

Mathews died in 1940 at age 79, and obituaries were published in both The Blood-Horse and Thoroughbred Times, as well as the Lexington Leader’s “Colored Notes.” The turf publications memorialized him thusly: “There was nothing connected with the routine on a Thoroughbred farm of which he was not a master.”

His funeral was at the house on Breckenridge Street, and he was buried in Greenwood Cemetery, which is now known as Cove Haven, among other prominent black horsemen.

Eric Brooks, curator at Ashland, the Henry Clay Estate in Lexington, said that there is little more in the estate’s records about Mathews, despite his long history with the farm.

“I don’t know what the real reality is,” Brooks said of Mathews’ roles. “Ashland Stud would have been considered one of the preeminent studs in the world at the time.”

Marty Perry with the Kentucky Heritage Council, which nominated the house for the National Register of Historic Places, said that he is hoping the intriguing information that sheds light on African-American history will help the house get the recognition the state believes it deserves. But he wishes more were known about the man himself.

“There is kind of an empty story here,” Perry said. The state has submitted the application and expects to hear something in a month or two.

House might have played other role in city history

Most of what is known about the Breckenridge Street home was pieced together by Sarah McCartt-Jackson, a Western Kentucky University graduate student who wrote the National Register application.

She became interested because her sister and brother-in-law, Melissa and Philip Smyth, bought the house and wanted to know the history of it. They had heard some interesting rumors in the neighborhood, including that the home might have also been a boardinghouse, a theory supported by numbered doors found stored in the basement.

Lexington historian Yvonne Giles thinks that might add another intriguing layer to the house’s history. She believes that after Mathews’ death, the house became the Brown Hotel. When major big bands would play Lexington’s all-white hotels such as the Phoenix, black musicians stayed at the Brown, Giles said.

Mathews’ story, and that of his house, add new dimensions to Lexington’s equine and social history, which is slowly being restored through finds such as the African Cemetery No. 2 on Seventh Street, where Isaac Murphy’s grave was rediscovered.

Current home owner Philip Smyth said he knew none of this when he bought the house at auction nearly 10 years ago for $68,000 plus fees. He knew of the unusual-looking house because his mother lives on Castlewood Drive nearby and he would walk through the neighborhood on his way to classes at the University of Kentucky.

The house is presently still divided into a duplex, but Smyth said he hopes to restore the structure to its previous glory. The house still has an air of grandeur, with seven hipped dormer windows, three original sandstone chimneys, and an unusual set of cut-stone box gutters.

But there is no sign of the role its former occupant once played in Kentucky’s signature industry.

Even those who have studied the state’s African-American history say Mathews’ story is new to them.

“Hearing about this revelation makes me all the more hopeful that this information will continue pushing to the surface,” said Anne Butler, a Kentucky State University historian, “This sounds like a very accomplished horseman