Descendants of an Election Day massacre reflect 100 years later

In 1920, a mob burned a Black community in Ocoee, Florida, because an African American man tried to vote. Today their families are still fighting for voter rights.

ON THE NIGHT of the 1920 election, the Bells, a Black family in Ocoee, Florida, heard that the Ku Klux Klan planned to incite violence in the town. They quickly decided to follow through with a desperate plan: The children would navigate the thick, swampy woods around Ocoee alone and meet their parents in a church in a neighboring town. With gunshots and flames in the distance, 18-year-old Allen Bell guided his six younger siblings through the wet brush while praying the group wouldn’t encounter snakes, alligators, or the KKK.

Before the family departed, Bell’s father ordered him to stay out of sight of any white man. “If they see you, they’ll kill you,” he warned. By the next day, their house and all of their possessions had gone up in flames. Bell, his siblings, and his parents made it to safety, but not everyone in their extended family survived.

On election night in 2020, Gladys Franks Bell, Allen Bell’s 81-year-old daughter, volunteered at a polling place, just as she has for the past decade, to carry on the legacy. As a poll deputy, she greeted and guided every voter who walked through the polling location’s doors in Plymouth, about 10 miles north of Ocoee, in the Orlando area.

“This election is very special to me, because 100 years ago my great-great-uncle July Perry lost his life because of voting,” she says.

During this year’s contentious election, voters in Ocoee felt especially called to the polls to honor the centennial of a massacre that started when a Black man simply tried to vote.

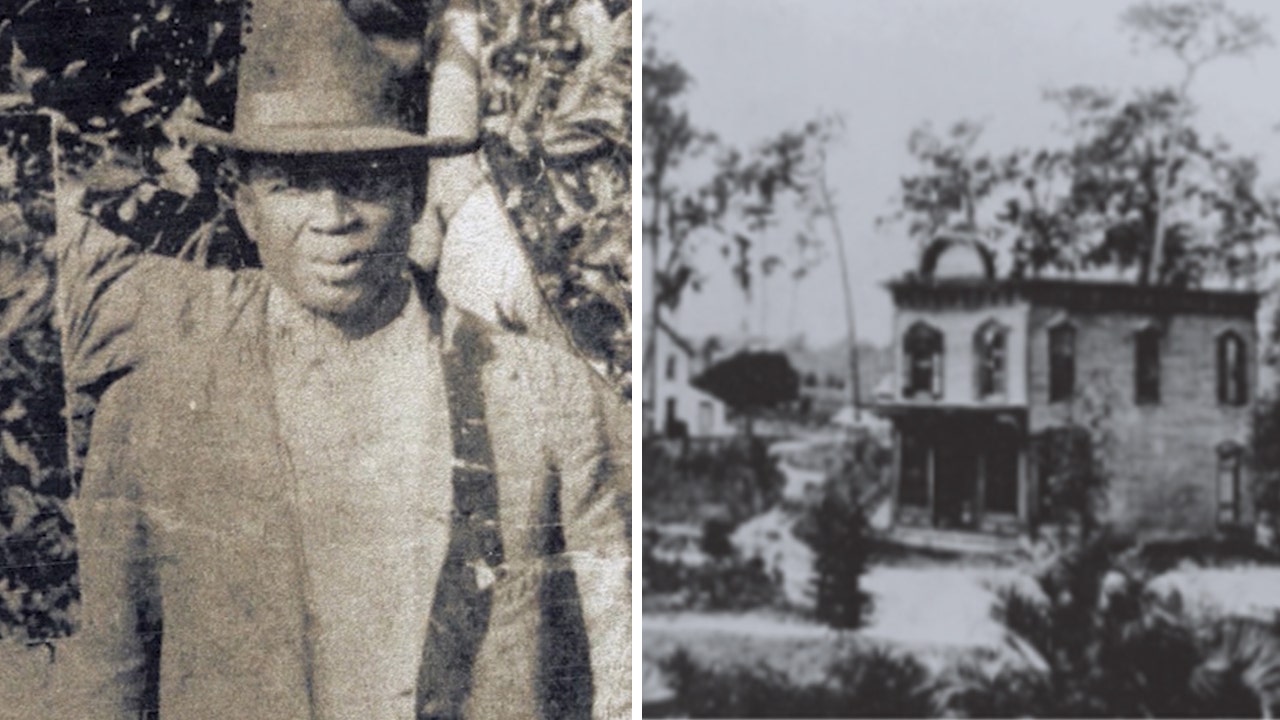

On November 2, 1920, Mose Norman, the successful Black owner of a 100-acre orange orchard and one of the first people in town to have a car, went to vote in Ocoee. Once at the polls, however, he was told he hadn’t paid his poll tax, a tax often cited to prevent Black Americans from voting.

Norman consulted an Orlando judge and then returned again to vote. The resulting confrontation incited a white mob.

Norman fled to the home of his friend Julius “July” Perry and then left town. Sam Salisbury, a Klu Klux Klan member and former Orlando chief of police, led the mob to Perry’s house, where a shootout occurred. Two white men were killed, and Perry and his 19-year-old daughter were injured. Perry was arrested but the mob broke him out of jail, in order to lynch him. Then they proceeded to destroy the town’s Black community.

Although the death toll is unknown, some estimate as many as 60 people died in the massacre. Twenty-two homes, two churches, and a lodge were also burned. After the election, the number of African Americans in Ocoee plummeted from 255 to two, according to census records. It became known as a “sundown town,” a place in which Black people would have been vulnerable and endangered after dark. As a result, they didn’t move back until the 1980s.

The Ocoee massacre was part of the Red Summer, a period of racial terror from 1917 to 1923, when white mobs razed prosperous Black communities across the country. In 1923, more than 10,000 white men burned Rosewood, another Florida town, to the ground. In an effort to make reparations, 71 years later Florida passed a law providing free in-state tuition to Rosewood descendants, along with $1.5 million to be divided between the remaining 11 or so survivors.

The city of Ocoee officially recognized the massacre two years ago, and now it’s working on a formal apology to descendants. This year legislation passed that requires the massacre be taught in Florida schools, and this week the city is holding memorial events for the centennial.

:strip_exif(true):strip_icc(true):no_upscale(true):quality(65)/d1vhqlrjc8h82r.cloudfront.net/06-24-2020/t_1eef7c6d5a904962822e45e37cd52556_name_image.jpg)

Yet despite a growing awareness of Ocoee’s violent past, descendants say Black voters still face challenges at the polls.

“We are 100 years into this and we are still dealing with voter intimidation, voter suppression, and issues of race and violence,” says Narisse Spicer, a great-granddaughter of John and Lucy Huckey, who survived the massacre with their two children by hiding in the woods. “It is definitely time, and well overdue, to start thinking about how we can change the future so that future generations don’t experience the same thing.”

J. Carl Devine, a great-grandchild of survivors John and Roxy Williams, sees similar trends in this year’s election. “I am seeing this election as they saw theirs,” said Devine. “After 100 years, some things haven’t changed… When one group is trying to suppress another group from voting, the whole constitution is in jeopardy. When one person is denied, all of us are denied.”

George Oliver, the city’s first Black commissioner, dreams of turning a one-acre lot believed to be an old African-American cemetery in Ocoee into a park where the community could honor the massacre victims. “I took an oath in this city to stand up for people that couldn’t stand, to fight for people that couldn’t fight, and to be a voice for people that don’t have a voice—and that’s [for those] dead and alive,” he says.

When Bell arrived home at 8:30 p.m., after 14 hours at the polling place, her back hurt. A shower helped—but so did knowing that she had supported the cause her great-great-uncle had died for.

She hopes that as more people learn about the Ocoee massacre, more will be inspired to vote. For years, no one spoke about the town’s violent past—but now, she says, other families are starting to tell their stories. She ended up writing a book about her father to answer her family’s endless questions about what happened that election night 100 years ago.

Bell’s son moved back to Ocoee more than five years ago and voted in town yesterday.

“He knows the story,” she says. “We keep the story going… and I told him that you voting there in Ocoee made it more significant.”