Over the next few years, segregation and black disenfranchisement picked up pace in the South, and was more than tolerated by the North. Congress defeated a bill that would have given federal protection to elections in 1892, and nullified a number of Reconstruction laws on the books.

Then, on May 18, 1896, the Supreme Court delivered its verdict in Plessy v. Ferguson. In declaring separate-but-equal facilities constitutional on intrastate railroads, the Court ruled that the protections of 14th Amendment applied only to political and civil rights (like voting and jury service), not “social rights” (sitting in the railroad car of your choice).

In its ruling, the Court denied that segregated railroad cars for blacks were necessarily inferior. “We consider the underlying fallacy of [Plessy’s] argument,” Justice Henry Brown wrote, “to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it.”

Alone in the minority was Justice John Marshall Harlan, a former slaveholder from Kentucky. Harlan had opposed emancipation and civil rights for freed slaves during the Reconstruction era – but changed his position due to his outrage over the actions of white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan.

Harlan argued in his dissent that segregation ran counter to the constitutional principle of equality under the law: “The arbitrary separation of citizens on the basis of race while they are on a public highway is a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and the equality before the law established by the Constitution,” he wrote. “It cannot be justified upon any legal grounds.”

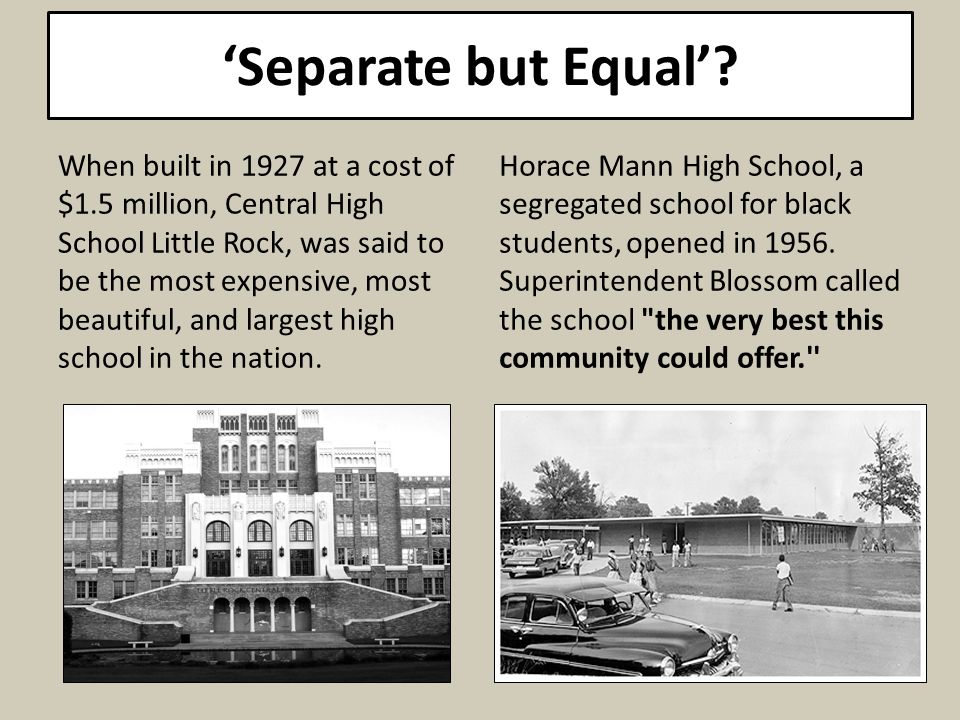

The Plessy v. Ferguson verdict enshrined the doctrine of “separate but equal” as a constitutional justification for segregation, ensuring the survival of the Jim Crow South for the next half-century.

Plessy legitimized the state laws establishing racial segregation in the South and provided an impetus for further segregation laws. It also legitimized laws in the North requiring racial segregation as in the Boston school segregation case noted by Justice Brown in his majority opinion. Legislative achievements won during the Reconstruction Era were erased through means of the “separate but equal” doctrine.

The doctrine had been strengthened also by an 1875 Supreme Court decision that limited the federal government’s ability to intervene in state affairs, guaranteeing to Congress only the power “to restrain states from acts of racial discrimination and segregation”. The ruling basically granted states legislative immunity when dealing with questions of race, guaranteeing the states’ right to implement racially separate institutions, requiring them only to be “equal”.

Intrastate railroads were among many segregated public facilities the verdict sanctioned; others included buses, hotels, theaters, swimming pools and schools. By the time of the 1899 case Cummings v. Board of Education, even Harlan appeared to agree that segregated public schools did not violate the Constitution.

The effect of the Plessy ruling was immediate; there were already significant differences in funding for the segregated school system, which continued into the 20th century; states consistently underfunded black schools, providing them with substandard buildings, textbooks, and supplies. States which had successfully integrated elements of their society abruptly adopted oppressive legislation that erased reconstruction era efforts. The principles of Plessy v. Ferguson were affirmed in Lum v. Rice (1927), which upheld the right of a Mississippi public school for white children to exclude a Chinese American girl. Despite the laws enforcing compulsory education, and the lack of public schools for Chinese children in Lum’s area, the Supreme Court ruled that she had the choice to attend a private school.

It would not be until the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, at the dawn of the civil rights movement, that the majority of the Supreme Court would essentially concur with Harlan’s opinion in Plessy v. Ferguson.