Today’s featured designers are a legend in North Carolina furniture craftsmanship (the wood furniture capitol of the USA) and a designer determined to continue that legacy.

Thomas Day (c. 1801 – 1861) was a free black American furniture designer and cabinetmaker in Caswell County, North Carolina. Day’s furniture-making business became one of the largest of its kind in North Carolina and distributing furniture to wealthier customers throughout the state. Much of Day’s furniture was produced for prominent political leaders, the state government, and the University of North Carolina. It is believed that Day produced no less than 1/3 of all furniture produced in the state at that time.

Day was born to free black parents parents in Dinwiddle County, Virginia around 1801. His family moved to North Carolina and settled in Caswell County in 1824. Day began his cabinetmaking business in Milton, North Carolina with his brother, John Day, Jr., but his brother would emigrate to Liberia in 1825, leaving the cabinetry business solely to Thomas. Incidentally, John Day, Jr. became one of the founding fathers of the Republic of Liberia. He served as Chief Justice, and was one of the first people to sign the Liberian Declaration of Independence.

Day’s furniture-making business employed the use of both black slaves and white apprentices, despite the general belief that Day (as a free man) was of lower social stature than his white apprentices.

Day was a successful businessman, at one point becoming a stockholder in the State Bank of North Carolina. Day owned significant real estate, including his place of business and his residence. This was highly unusual for a free person of color in the era before the Civil War. Day used to steam-power to drive much of his furniture-making implements, greatly increasing his production volume and efficiency.

In contrast to carpentry and milling of its time (which were mostly produced as separate entities), Day’s creations were crafted, unique pieces—each playing an essential role in the over-all architectural composition. Day considered his parlor designs to be the pinnacle of his projects. He fabricated his custom millwork as extensions of the style used in the parlor. His distinctive woodwork in these types of rooms often included an elaborate mantel between two arched niches. The dramatic effect caused by the resultant variety of depth is a unique characteristic of Day’s parlors.

Day’s mantels are also exceptionally detailed, as they were the central focus of the parlor. A Day mantel consists of a thick shelf supported by columns that appear to be freestanding.

Although Day’s shop was prolific in its manufacturing volume and variety, the pieces most commonly attributed to Day are crafted in the American Empire style. Designs typically included well-proportioned curves and a masterful use of negative spaces. His pieces are often expertly veneered with walnut and mahogany.

Day’s skills were sought by many plantation owners whose homes he embellished with stylish mantle pieces, stair railings, and newell posts, in addition to providing them with fashionable furniture that reflected the latest urban styles and were often distinguished by Day’s unique touch.

The Holt Plantation in Alamance County, North Carolina, belonged to the wealthiest man in North Carolina, textile manufacturer E.M. Holt. His son Thomas became governor of the state in 1891. Thomas Day created the furniture for the home which has been restored and is now a museum and listed with the National Register of Historic Places. Below are pictures of the parlor and dining rooms:

Day maneuvered through the complex legal sanctions that confronted free blacks at the time, sometimes with the assistance of wealthy and influential white patrons. For example, a law had been passed in 1827 that prohibited free blacks from migrating into the state. He was affected by the law in 1830 when he married a free black Virginian, Aquilla Wilson Day. Sixty-one white citizens of Milton presented a petition to the state legislature asking that an exception be made to the 1827 law so that Aquilla could move across the state line to Milton and live with her husband. The exception was made in late December 1830 and Aquilla and Thomas were able to begin their life together as man and wife in North Carolina.

In 1835 Day attended the Fifth Annual Convention for the Improvement of Free People of Colour in Philadelphia. There he associated with some of the most successful and influential African American leaders in the nation, many of whom were or would soon become leaders in the struggle to end slavery. Most historians believe that Day would not have been present at such a meeting were he not sympathetic to the abolitionist cause, an argument that appears to be at odds with the fact that Day was a slave owner himself. However, many historians point out that free black slaveowning was sometimes a “protective cover” Southern free blacks deployed to show solidarity with the racial status quo of white supremacy. In other words, by owning slaves Day outwardly demonstrated his loyalty to the values of white supremacy, but there’s evidence he did not fully share those values. Other actions he took indicate he had very different values regarding the institution of slavery and desired to inculcate his children with them. For example, he sent his three children to an abolitionist-sympathizing school, Wesleyan Academy in Wilbraham, Massachusetts and was on very friendly terms with its radical abolitionist leaders. Research suggests that he may have met the leaders of Wesleyan at a major meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society in New York City in 1840, where a person by his name was listed in the attendance roster. In sum, increasingly evidence supports the theory that Day, while seeming to share the values of the social and cultural milieu within which he lived in North Carolina, was likely a “closet abolitionist.”

By 1850, Day’s shop was the largest in the state. Because he was one of the earliest furniture makers to use steam-powered tools and mass production techniques in North Carolina, he is considered a founding father of the modern Southern furniture industry.

By the end of his life, Thomas Day began to fall victim to a major economic recession and the ever-tightening racial order. His business was in receivership by the time of his death on the eve of the Civil War. His son, Thomas Jr., received a loan from business associates of his father’s and was able to continue to operate the business and to pay off its debts in a few years. By 1865, Day’s widow, Aquilla, his daughter, Mary Ann and Thomas Jr. were living in Wilmington, North Carolina. There they were prominent members of the activist free black community described in a contemporary news article as being fully supportive of the Union cause. In Wilmington, Mary Ann Day helped establish a school for formerly enslaved black children and used her own funds to purchase supplies. The school was started in 1865 before the fall of the Confederacy.

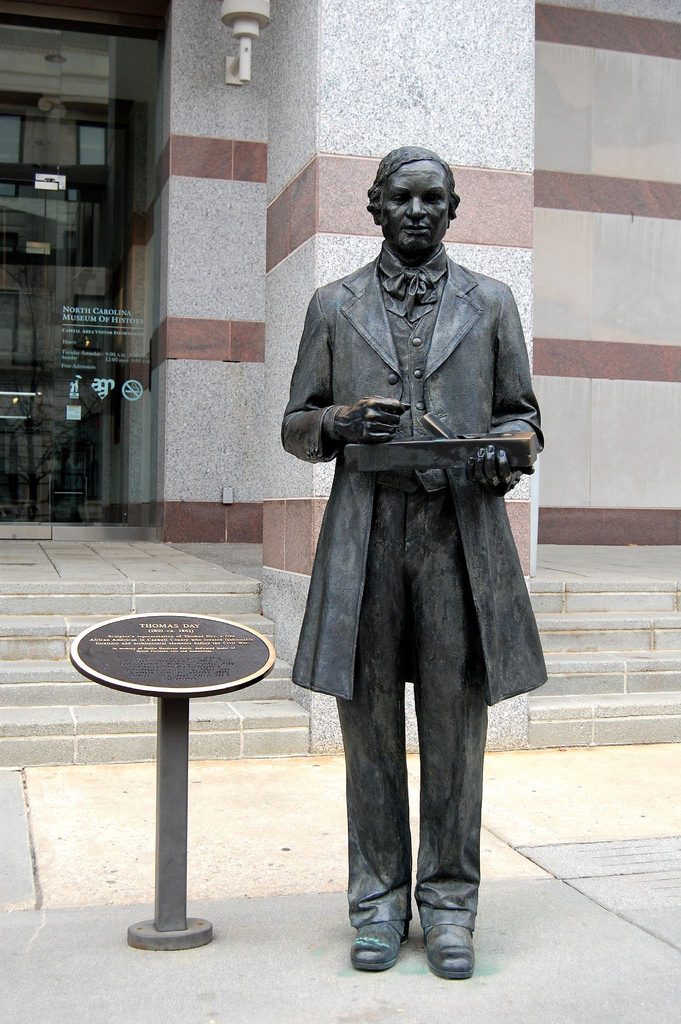

A statue of Thomas Day stands outside the North Carolina Museum of History. His home and workshop are listed on the National Register of Historic Places and was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1975.

The North Carolina Museum of History has the largest collection of Day’s furniture.

Jerome Bias makes furniture using 18th century woodworking techniques. He has a passion for furniture made in North Carolina during the 18th and 19th centuries, especially the furniture of Thomas Day. Day was a successful 19th century African-American furniture maker from Milton, North Carolina, whose pieces are highly valued today. Currently, Mr. Bias is working on a series of blanket chests which are adaptations of a 17th century walnut blanket chest from eastern North Carolina.

Largely self-taught, Jerome has been practicing the arts and mysteries of woodworking for the last eleven years. Over those years, he has developed his skills and studied the works of Thomas Day and other African-American craftsmen in antebellum North Carolina.

Jerome has given period-correct woodworking demonstrations for the Thomas Day Education Project, North Carolina Museum of History, Charlotte Hawkins Brown Museum, Tillery Resettlement Community, Historic Stagville and Duke Homestead. He currently serves on the Advisory Board for the exhibit, Behind the Veneer: Thomas Day Master Cabinet Maker at the North Carolina Museum of History. In August, 2009, Bias was honored with an exhibit and demonstration at Horace Williams House in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Originally a native of Scotland Neck, North Carolina, Bias lives in rural Orange County, North Carolina. He has converted a spare bedroom of his 100-year-old farmhouse into his workshop.