Happy Hump Day POU! Today we remember Sarah Baartman.

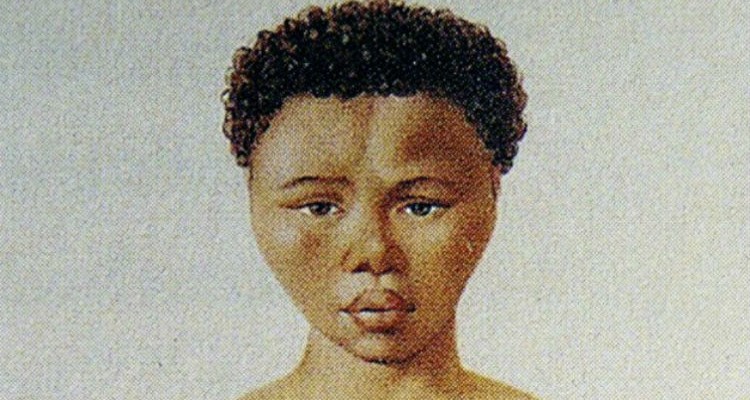

Sarah Baartman (also spelled Sara, sometimes in the diminutive form Saartje) (before 1790 – 29 December 1815), was the most well known of at least two South African Khoikhoi women who, due to their large buttocks, were exhibited as freak show attractions in 19th-century Europe under the name Hottentot Venus—”Hottentot” was the name for the Khoi people, now considered an offensive term, and “Venus” referred to the Roman goddess of love.

Sara Baartman was born to a Khoisan family in the vicinity of the Gamtoos River in what is now the Eastern Cape of South Africa, on land taken over by Dutch farmers. Her father was killed by Bushmen while driving cattle.

Baartman spent her childhood and teenage years on settler farms. She went through puberty rites, and kept the small tortoise shell necklace, probably given to her by her mother, until her death in France. In the 1790s, a free black (the Cape designation for individuals of enslaved descent) trader named Peter Cesars met her and encouraged her to move to Cape Town, which had recently come under British control. Records do not show whether she was made to leave, or went willingly, or was sent by her family to Cesars. She lived in Cape Town for at least two years working in households as a washerwoman and a nursemaid, first for Peter Cesars, then in the house of a Dutch man in Cape Town. She moved finally to be a wet-nurse in the household of Peter Cesars’ brother-in-law, Hendrik Cesars, outside of Cape Town in present day Woodstock.

Sara Baartman lived alongside slaves in the Cesars’ household. William Dunlop, a Scottish military surgeon in the Cape slave lodge, with a sideline in supplying showmen in Britain with animal specimens, suggested she travel to England to make money by exhibition. Baartman refused. Dunlop persisted and Sara Baartman said she would only go if Hendrik Cesars came too. He also refused, but became ever more in debt in part because of unfavorable lending terms because of his status as free black. Finally, in 1810 he agreed to go to England to make money through putting Sara Baartman on stage. The party left for London in 1810. It is unknown if Sara Baartman went willingly or was forced, but she was in no position to refuse even if she chose to do so.

Dunlop was the frontman and conspirator behind the plan to exhibit Sara Baartman: According to an English law report of 26 November 1810, an affidavit supplied to the Court of King’s Bench from a “Mr. Bullock of Liverpool Museum” stated: “some months since a Mr. Alexander Dunlop, who, he believed, was a surgeon in the army, came to him sell the skin of a Camelopard, which he had brought from the Cape of Good Hope…Some time after, Mr. Dunlop again called on Mr. Bullock, and told him, that he had then on her way from the Cape, a female Hottentot, of very singular appearance; that she would make the fortune of any person who shewed her in London, and that he (Dunlop) was under an engagement to send her back in two years…” Lord Caledon, governor of the Cape, gave permission for the trip, but later said regretted it after he fully learned the purpose of the trip.

Hendrik Cesars and Alexander Dunlop brought Baartman to London in 1810. The group lived together in Duke Street, St. James the most expensive part of London. In the household were Sara Baartman, Hendrik Cesars, Alexander Dunlop, and two African boys, probably brought illegally by Dunlop from the slave lodge in Cape Town.

Dunlop schemed to have Sara exhibited and Cesars was the showman. Dunlop exhibited Baartman in the Egyptian Hall of Piccadilly Circus on November 24, 1810. Dunlop thought he could make money because of Londoners’ lack of familiarity with Africans and because of Baartman’s large bottom. Crais and Scully say: “People came to see her because they saw her not as a person but as a pure example of this one part of the natural world”.

A handwritten note made on an exhibition flyer by someone who saw Baartman in London in January 1811 indicates curiosity about her origins and probably reproduced some of the language from the exhibition: “Sartjee is 22 Years old is 4 feet 10 Ins high, and has (for an Hottentot) a good capacity. She lived in the occupation of a Cook at the Cape of Good Hope. Her Country is situated not less than 600 Miles from the Cape the Inhabitants of which are rich in Cattle and sell them by barter for a mere trifle, A Bottle of Brandy, or small roll of Tobacco will purchase several Sheep – Their principal trade is in Cattle Skins or Tallow. – Beyond this Nation is an other, of small stature, very subtle & fierce; the Dutch could not bring them under subjection, and shot them whenever they found them. 9th Jany. 1811. [H.C.?]”

The tradition of freak shows was longstanding in Britain at this time, and historians have argued that this is at first how Baartman was displayed. Baartman never allowed herself to be exhibited nude and an account of her appearance in London in 1810 makes it clear that she was wearing a garment, albeit a tight-fitting one.

Her exhibition in London just a few years after the passing of the Slave Trade Act 1807 created a scandal. This is in part because British audiences misread Hendrik Cesars, thinking he was a Dutch farmer, boer, from the frontier. Scholars have tended to reproduce that error, but tax rolls at the Cape show he was free black. Violence was part of the show. An abolitionist benevolent society called the African Association conducted a newspaper campaign for her release. Zachary Macaulay led the protest. Hendrik Cesars protested that Baartman was entitled to earn her living, stating: “has she not as good a right to exhibit herself as an Irish Giant or a Dwarf?” Cesars was comparing Baartman to the contemporary Irish giants Charles Byrne and Patrick Cotter O’Brien. Macaulay and The African Association took the matter to court and on November 24, 1810 at the Court of King’s Bench the Attorney-General began the attempt “to give her liberty to say whether she was exhibited by her own consent.”

In support he produced two affidavits in court. The first, from a Mr Bullock of Liverpool Museum, was intended to show Baartman had been brought to Britain by persons who referred to her as if she were property. The second, by the Secretary of the African Association, described the degrading conditions under which she was exhibited and also gave evidence of coercion. Baartman was then questioned before an attorney in Dutch, in which she was fluent, via interpreters. However the conditions of the interview were stacked against her, in part again because the court saw Hendrik Cesars as the boer exploiter, rather than seeing Alexander Dunlop as the organizer. They thus ensured that Cesars was not in the room when Baartman made her statement, but Dunlop was allowed to remain.

Historians have stated that this therefore casts great doubt on the veracity and independence of the statement that Baartman then made. She stated that she in fact was not under restraint, did not get sexually abused, and that she came to London on her own free will. She also did not wish to return to her family and understood perfectly that she was guaranteed half of the profits. The case was therefore dismissed. She was questioned for three hours. The statements directly contradict accounts of her exhibitions made by Zachary Macaulay of the African Institution and other eyewitnesses. A written contract was produced, which is considered by some modern commentators to be a legal subterfuge.

The publicity given by the court case increased Baartman’s popularity as an exhibit. She later toured other parts of England and was exhibited at a fair in Limerick, Ireland in 1812. She also was exhibited at a fair at Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk.

A man called Henry Taylor took Sara Baartman to France, from around September 1814. Taylor then sold her to an animal trainer, S. Réaux, who exhibited her under more pressured conditions for fifteen months at the Palais Royal. In France she was in effect enslaved. In Paris, her exhibition became more clearly entangled with scientific racism. French scientists were curious about whether she had the elongated labia which earlier naturalists such as François Levaillant had purportedly observed in Khoisan at the Cape. French naturalists, among them Georges Cuvier, head keeper of the menagerie at the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle,and founder of the discipline of comparative anatomy visited her. She was the subject of several scientific paintings at the Jardin du Roi, where she was examined in March 1815: as Saint-Hilaire and Frédéric Cuvier, a younger brother of Georges, reported, “she was obliging enough to undress and to allow herself to be painted in the nude.” This was not literally true: although by his standards she appeared to be naked, in accordance with her own cultural norms of modesty throughout these sessions she wore a small apron-like garment which concealed her genitalia. She steadfastly refused to remove this even when offered money by one of the attending scientists. In Paris, Baartman’s promoters didn’t need to concern themselves with slavery charges. Crais and Scully state: “By the time she got to Paris, her existence was really quite miserable and extraordinarily poor. Sara was literally treated like an animal. There is some evidence to suggest that at one point a collar was placed around her neck.”

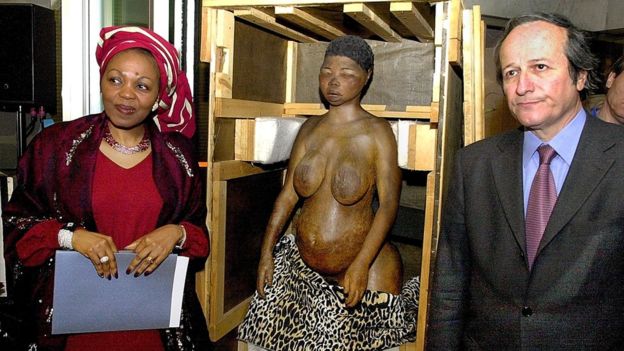

Baartman died on 29 December 1815 at age 26, of an undetermined inflammatory ailment, possibly smallpox, while other sources suggest she contracted syphilis, or pneumonia. During the lengthy negotiation to have Baartman’s body returned to her home country after her death, the assistant curator of Musee de l’homme, Philippe Mennecier argued against her return stating: “we never know what science will be able to tell us in the future. If she is buried, this chance will be lost … for us she remains a very important treasure.” Cuvier conducted a dissection,and displayed her remains, but did not do an autopsy to inquire into the reasons for Baartman’s death. For more than a century and a half, visitors to the Museum of Man in Paris could view her brain, skeleton and genitalia as well as a plaster cast of her body. After numerous protests, her remains were returned to South Africa in 2002 and she was buried in the Eastern Cape on South Africa’s National Women’s Day.