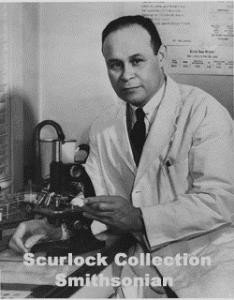

Charles R. Drew was born June 3, 1904, in Washington, D.C. He attended Amherst College in Massachusetts, where his athletic prowess in track and football earned him the Mossman trophy as the man who contributed the most to athletics for four years. He then taught biology and served as coach at Morgan State College in Baltimore before entering McGill University School of Medicine in Montreal.

As a medical student, Drew became an Alpha Omega Alpha Scholar and won the J. Francis Williams Fellowship, based on a competitive examination given annually to the top five students in his graduating class. He received his MD degree in 1933 and served his first appointment as a faculty instructor in pathology at Howard University, from 1935 to 1936. He then became an instructor in surgery and an assistant surgeon at Freedman’s Hospital, a federally operated facility associated with Howard University.

In 1938, Drew was awarded a two-year Rockefeller fellowship in surgery and began postgraduate work, earning his Doctor of Science in Surgery at Columbia University. His doctoral thesis, “Banked Blood” was based on an exhaustive study of blood preservation techniques. It was while he was engaged in research at Columbia’s Presbyterian Hospital that his ultimate destiny in serving mankind was shaped. The military emergency of World War II had a demanding vital need for information and procedures on how to preserve blood.

As the European war scene became more violent and the need for blood plasma intensified, Drew, as the leading authority in the field, was selected as the full-time medical director of the Blood for Britain project. He supervised the successful collection of 14,500 pints of vital plasma for the British. Out of his work came the American Red Cross Blood Bank. In February 1941, Drew was appointed director of the first American Red Cross Blood Bank, in charge of blood for use by the U.S. Army and Navy.

During this time, Drew agitated the authorities to stop excluding the blood of African-Americans from plasma-supply networks, and in 1942, he resigned his official posts after the armed forces ruled that the blood of African-Americans would be accepted but would have to be stored separately from that of whites.

The NAACP awarded him the Spingarn Medal in 1944 in recognition of his work on the British and American projects. Virginia State College presented him an honorary doctor of science degree in 1945, as did his alma mater Amherst in 1947.

Drew returned to Freedman’s Hospital and Howard University where he served as a professor of medicine and surgeon from 1942 to 1950. On April 1, 1950, Drew was motoring with three colleagues to the annual meeting of the John A. Andrews Association in Tuskegee, Alabama, when he was killed in a one-car accident. The automobile struck the soft shoulder of the road and overturned. Drew was severely injured and rushed to nearby Alamance County General Hospital in Burlington, North Carolina. In the words of his widow, “everything was done in his fight for life” by the medical staff. However, it was too late to save him.

At his untimely death, Drew left behind a devoted wife, Lenore, four children and a legacy of inspirational, unstinting dedication to service for all people. In 1981, the U.S. Postal Service paid tribute to Drew by issuing in his honor, a stamp in the GREAT AMERICANS Series.