Samuel Sewall, a Boston-based abolitionist lawyer, was not expecting a delivery from Rome. So he was understandably shocked to find a three-foot-tall marble sculpture waiting for him at the city’s port one day in 1868. The accompanying $800 bill for the artwork came as a second, less welcome, surprise.

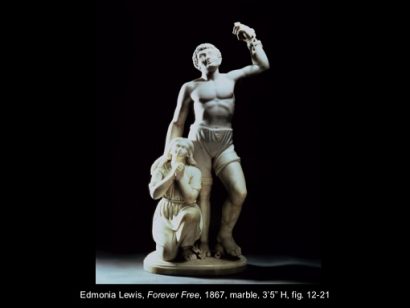

Titled Forever Free (1867), the work had been sent by sculptor Edmonia Lewis and depicted a newly freed African-American couple. It celebrated the recent Emancipation Proclamation that had declared, on January 1, 1863, that “all persons held as slaves within any State… shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

Like her uncommissioned sculpture, Lewis was used to being a surprise arrival on the art scene. As a woman of mixed African and Native American descent who came of age during the Civil War, her odds of making it were slim, at best. Yet she managed to become the world’s first professional African-American sculptor, celebrated internationally for her Neoclassical style. “The obstacles Edmonia Lewis overcame are unparalleled in American art,” wrote Harry Henderson in the 1993 volume A History of African American Artists: From 1792 to the Present (co-authored with artist Romare Bearden.

Orphaned at a young age, Lewis was raised by her mother’s Chippewa sisters in upstate New York. In 1859, supported by her brother, she traveled to Ohio to attend Oberlin College. There, she received drawing instruction from an experienced artist, Georgianna Wyett, and saw her first plaster casts of classical sculptures.

Oberlin, which admitted both female and African-American students, was a major abolitionist center at the time. Yet Lewis still faced discrimination. Falsely accused of poisoning her roommates and stealing art supplies, she was denied the right to enroll for her final semester and was therefore unable to graduate. To continue her studies, Lewis moved to Boston with a letter of introduction that secured her training under self-taught sculptor Edward Brackett. Although he was helpful, Lewis eventually decided it would be best to leave the United States. In the summer of 1865, the young sculptor boarded a ship to join the growing number of American artists working in Italy.