Howard “Stretch” Johnson, a charismatic Harlemite who graduated from Cotton Club dancer to Communist Party youth leader, once claimed that in late 1930s New York “75% of black cultural figures had Party membership or maintained regular meaningful contact with the Party.” He stretched the truth, but barely.

The magnetic appeal of communism for African American writers proved widespread throughout the 20th century. The chief attraction was the frontline role of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) in fighting racism and colonialism, combined with the Communist movement’s cutting-edge support of radical multiculturalism in the arts.

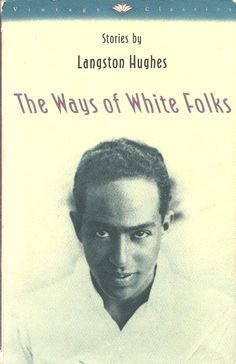

During the Popular Front era the party attracted support from a number of the brightest lights in African-American literature, including Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison and Chester Himes.

Often associated with a flourishing of art, music and literature, the Communist Party found a home in Harlem during the Depression. The Party helped fund such cultural organizations as the Federal Negro Theatre, which employed 350 people and gave black playwrights a chance to come to life and the Federal Writers Project that studied the role and history of blacks on the New York scene. They also funded the Harlem Community Arts Center, which helped to present a free stage for many of Harlems artists. These projects gave a tremendous boost to the morale in Harlem. In 1936 the Communist Party also began action to ensure equality in sports.

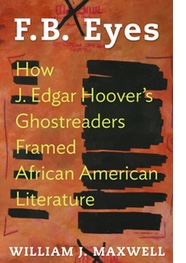

When Black Writers Were Public Enemy No. 1

Decades before today’s tensions between black communities and the police, J. Edgar Hoover’s ghostreaders targeted literary legends as dangerous dissidents. The following article by researcher William Maxwell describes the history of African American writers with ties to leftist politics and the federal governments attempts to silence them.

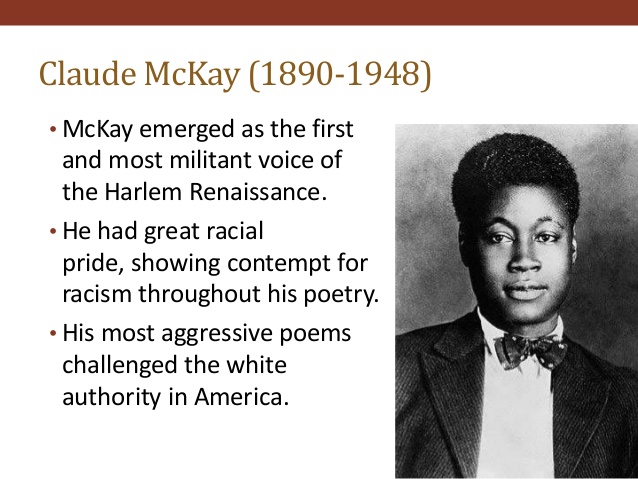

As the textbooks tell it, 1922 was the annus mirabilis—the “wonderful year” of modernist literature in English. James Joyce’s Ulysses, the novel that changed everything but the Ireland it dissected, was published in Paris; T.S. Eliot revealed in The Waste Land that April, despite appearances, is the “cruelest month”; and Claude McKay announced the arrival of the Harlem Renaissance with the movement’s first book of poetry, Harlem Shadows.

In the mind of the young FBI, however, McKay’s 1922 was most notable as a year of revolutionary danger. When other readers were appreciating “If We Must Die” and the rest of the poet’s fierce but well-mannered Shakespearian sonnets, Bureau bookworms—agents tasked with screening texts like McKay’s—were warning of a “collection of radical poems” composed by “a notorious negro revolutionary.”

In the summer of 1922, a “strictly confidential source” dropped word that the Jamaican-born poet and “well-known radical of New York City” planned a trip to the Soviet Union, the home of the Russian Revolution, which the left-wing McKay suspected might be “the greatest event in the history of humanity.” Following McKay’s embarking on the trip that fall, the FBI’s surveillance system plunged into overdrive: cross-examining ship schedules, scouring McKay’s passport records and pressing a distant acquaintance for clues in her Harlem apartment. Immigration and customs officials were ordered to confine man, baggage and documents for “appropriate attention” should McKay attempt to reenter the United States. The ports of New York and Los Angeles, Seattle and Portland, New Orleans and Baltimore, were all put on notice, with FBI agents in Maryland boasting of a local police department on the “lookout” for one “Claude McKay (colored).” For more than a decade, McKay, well aware he was afflicted by government spies, reasoned that U.S. authorities would not let him back into the country “without special intervention.” The poet would live abroad until 1934, spending most of his Harlem Renaissance wary of returning to Harlem.

The FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover-era surveillance of so-called dissidents—a motley assembly of Soviet sympathizers, anti-war activists and civil rights leaders—has been well documented since the 1970s. But McKay was the first, though hardly the last, of one Hoover-tracked subculture that has received less attention: black writers, including some of the most celebrated names in American letters. In the heart of the 20th century, beginning decades before the FBI’s campaign against Martin Luther King Jr., the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and, later, the Black Panthers, dozens of allegedly subversive African-American poets, novelists, essayists and playwrights were distinct targets of the agency, whose surveillance of this group was thorough, far-reaching and sometimes ruthless.

Richard Wright

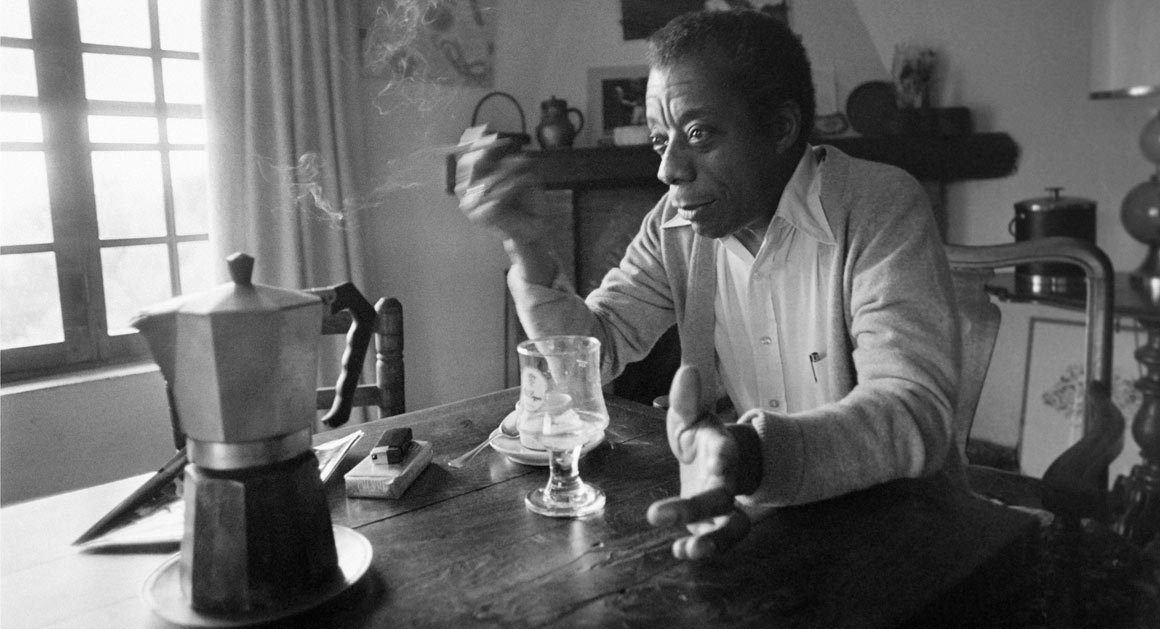

The extensive scope of this surveillance is only now coming into focus, thanks to the U.S. Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). Building on the detective work of prior researchers who discovered files on the likes of James Baldwin, Langston Hughes and Richard Wright, I submitted more than 100 FOIA requests for my recent book and found that the Washington, D.C., headquarters of the FBI opened at least 51 files on individual black writers active during the Hoover years. My 106 FOIA requests have returned almost 14,000 pages of files in all; the average length of the 45 files with page numbers we can count is a healthy 309 pages.

Measured more narrowly, nearly half—23 out of a total of 48—of the historically relevant writers featured in the classroom staple The Norton Anthology of African American Literature were first anthologized by the Bureau, where agents combed works of literature for signs of dissidence. The FBI, it turns out, may have been one of history’s most dedicated critics of African-American literature.

Not that the agency’s surveillance was confined to academic-style close reading. Alarmingly, the disclosed files reveal that the FBI prepared preventive arrests of most of the names dropped above, and altogether more than half of the black authors stalked in its archive. Twenty-seven of 51, accused of communism and related extremisms, were caught in the invisible dragnet of the agency’s “Custodial Detention” index and its successors—hot lists of pre-captives “whose presence at liberty in this country in time of war or national emergency,” Hoover resolved in 1939, “would be dangerous to the public peace and the safety of the United States Government.”

The first part of the FBI’s file on the writer Claude McKay, including reports on McKay’s passport records, as well as orders for immigration and customs officials to hold him for questioning upon reentry to the United States after a trip to the Soviet Union.

Reasons for inclusion in the secret Custodial index were broad and fuzzy. Anyone suspected of “affiliation with organizations engaged in activities in behalf of a foreign nation, participation in dangerous subversive movements, advocacy of the overthrow of Government by force and violence, et cetera,” could be added, Hoover advised. Hoover was, after all, a lawman who ever sought to recriminalize treacherous expression: Some 16 years after the Sedition Act had been repealed, he told the New Yorker he would “view with favor the passage of legislation making the advocacy of violent revolution a crime in itself.”

While the “et cetera” in the FBI’s surveillance mission allowed for the widest of roundups, the criteria for listings on the basis of “advocacy” were specially attuned to literary offenders: Hoover instructed that Custodial Detention candidates should be investigated through “public libraries” and “newspaper morgues.” Non-black writing could be targeted, of course; Joyce and Eliot were both watched by the FBI, with the latter attracting a short file devoted to left-wing objections to his anti-Semitism. But inside Hoover’s Bureau, black writing was more often found guilty of speaking for revolution and against the U.S. government until proven innocent; according to the best seized evidence, African-American writers were disproportionately trailed, studied and subjected to the Custodial Detention index. The ugliness of Hoover’s personal racism, honed in a segregating turn-of-century Washington and complicated by rumors of his own black ancestry, has been exaggerated by some biographers. But the strength of his conviction that black self-assertion needed watching cannot be overstated. The director informed Congress in 1964, for instance, that the FBI’s concern with radical influence on African-American protest was deep, abiding and unbreakable.

Just who, and whose literary work, was caught up in the Bureau’s monitoring of African-American writing? Scrutinizing African-American authors was an institutional passion of the FBI that stretched from the Red Summer of 1919, Hoover’s first year at the Bureau as well as the first year of Harlem’s renaissance, to Hoover’s death in the Bureau saddle in 1972. As the newly named head of the Bureau’s Radical Division, the twenty-something Hoover first trained on the laboratory of modern black art the FBI’s legendary system for archiving and exploiting the results of intelligence work. Gwendolyn Bennett, Sterling Brown, W. E. B. Du Bois, Georgia Douglas Johnson, Alain Locke, George Schuyler, as well as Hughes and McKay: All these Harlem Renaissance stars were eventually favored with FBI files, the nation’s highest medal of radical honor—some thin (Douglas Johnson’s is all of six sheets) and some as thick as windy literary biographies (Du Bois’ scales 756 pages).

While the Bureau’s voguish interest in Harlem’s “New Negroes” faded during the Great Depression, its inspection of African-American writing persisted from World War II through the militant Black Arts movement unveiled in 1965. In the early 1940s, worried over black attitudes to the war effort, the FBI began compiling files on such traveling targets as Wright, Chester Himes and Barack Obama mentor Frank Marshall Davis (a poet-journalist recently rescued from posthumous neglect by Rudy Giuliani and other conservative literati).

In the depths of the Cold War, a busy season of FBI literary criticism, no fewer than 22 African-American authors were first tracked by Bureau paperwork, among them Ralph Ellison and Lorraine Hansberry. (Hansberry’s now family-friendly drama A Raisin in the Sun (1959) was reviewed by an incognito FBI agent even before reaching Broadway. The four-page paper that resulted would receive a non-inflated “A” in my introductory African-American literature class.) Three Cold War files created in the 1950s—for Baldwin, Hoyt Fuller and Black Arts founder Amiri Baraka—looked forward to the last great wave of FBI book-clubbing: an elaborate counterintelligence program, well documented in the Senate’s Church Committee report of 1976, to imitate and subvert the literature of Black Power in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

It should be noted that records of the FBI’s rendezvous with 20th-century African-American writing are not fully accessible. For instance, the file of Margaret Walker—a winner of the Yale Younger Poets prize and the author of the novel Jubilee (1966), an influential revision of slavery—has been destroyed under a mysteriously named federal Records Retention Plan, wrongly condemned for lacking historical importance. And we can only guess at the presence of dossiers on many later black writers—Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni and other living Black Arts veterans—given that the Bureau stipulates (sanely) that third-party historians may examine copies of personal FBI files only after their subjects’ deaths.

Still, the available files more than suffice to reveal an FBI that was fixated on the labors of black writers. Hoover and dozens of lesser ghostreaders—my name for the FBI’s furtive and usually anonymous critic-spies—absorbed scores of African-American poems, plays, essays, stories and novels, as well as political polemics and intercepted correspondence—some even before publication, with the aid of bookish informers at major publishers and magazines. (Both the Reader’s Digest and the Daily Worker contained Bureau moles.) In turn, these anointed ghostreaders filed various reports on their findings, rivaling the productivity of their academic peers and occasionally falling into the pleasures of the enemy text. The reviewer of Hansberry’s Raisin in the Sun—his name lost to FOIA redaction—couldn’t help but enjoy an attractive and insightful dramatization of black “aspirations, the problems inherent in their efforts to advance themselves, and varied attempts at arriving at solutions.”

A few of the most prominent ghostreaders were specially trained FBI executives. Robert Adger Bowen of the early Bureau’s Office of Translations and Radical Publications had been a Cornell graduate student in literature and a successful minor novelist known for his Uncle Remus-style black dialect fiction. FBI assistant director William C. Sullivan, now best remembered as the likely author of the Bureau’s infamous 1964 “ suicide letter” to Martin Luther King Jr., had begun his working life as a Massachusetts school teacher and would-be English professor.

Most ghostreaders, however, were nose-to-the-street FBI special agents given a temporary reading assignment. Unlike Bowen and Sullivan, the typical special agent of the Hoover era entered the FBI as a sturdy white male law graduate seeking a patriotic plum job. (Between 1924, Hoover’s first year as FBI director, and 1933, the first year of FDR’s Bureau-friendly first term, the proportion of special agents with legal training rose from 30 to 74 percent.) As the social convulsions of the late-1960s isolated “Bureau think” from the higher reaches of American university culture, Hoover’s institution was obliged to hire some recruits with undergraduate degrees alone, provided that they also had three years of relevant work experience. A B.A. remained a requirement for all special agents, which meant that FBI readers continued to chase literary bad guys with help from at least a smattering of required college courses in English and composition. Given this general level of acquaintance with academic literary criticism—better than nodding but short of expert, often flavored by subsequent legal education in statutory interpretation—the inclination of FBI ghostreading to rely on the least demanding approaches of U.S. English departments makes good sense.

Prior to World War II, this inclination meant that FBI spy-criticism, like much of the academic literary criticism of the day, was ruled by biographical approaches; Bureau ghostreaders then agreed with many English professors that works of poetry, drama and fiction were elaborate confessions of an author’s personal history and future intent. Characteristically, one contributor to McKay’s FBI file reasoned that since the “[s]ubject is apparently a poet, or at least he his written considerable verse,” his “views, beliefs, principles, et cetera may properly be inferred from quotations from his writings.”

After World War II, FBI critics began to internalize the New Criticism, and its dogma that authors were separate and apart from the “speakers” who narrated their fictions. A report in the file of Black Arts writer Larry Neal thus takes unexpected pains to distinguish between his own racial politics and that of his knowingly drawn radical characters; Neal’s “occupation of being a writer,” theorized one indulgent ghostreader, “may have motivated his desire to acquire knowledge of the racial movement, without influencing his personal beliefs.”

Whatever its other effects, the ghostreaders’ sympathy for the New Criticism helped them to prepare for the imaginative demands of the COINTELPRO era of the late 1960s and early 1970s, when FBI critics of black writing, almost universally white, were asked to become pseudo-black writers themselves. In 1967, the FBI opened a COINTELPRO, or dedicated counterintelligence program, against so-called “Black Nationalist/Hate Groups.” When not conspiring to douse the offices of the Black Panther Party newspaper with what a Senate report later described as “a scent of the most foul smelling feces available,” the literary-critical wing of this COINTELPRO was asked to misdirect and discredit African-American expression through unflattering imitation.

Dozens of G-Men stole time from the period’s turmoil to mimic works of Black Power-style literature, concocting hundreds of would-be black poems, letters, comics, political platforms and at least one entire newspaper falsely attributed to the Black Student Union at Southern Illinois University. In one representative effort, New York-based author-agents composed and anonymously distributed copies of a comic ode to the courage of H. Rap Brown, the Black Panther and SNCC veteran famous for finding violence as American as cherry pie: “Old Rap Brown / Came to town / With his shades / Hanging down. / He hollered fight / Take what’s right / Then he flew, man / In the night.” (The superfluous-but-syncopating “man” in line seven was meant as an authenticating, “blackening” touch.)

What, in the end, was ghostreading’s practical impact on African-American literature? Proof of book-killing or stop-the-presses FBI censorship is lacking. Traces of subtler self-censorship among the many black writers who knew they were Bureau suspects are also few. On the contrary, the record suggests that African-American writers regularly transformed the burden of surveillance into creative inspiration. From the earliest journalism of the Harlem Renaissance to the performance-ready poetry of the Black Arts movement, these well-tracked writers wrote openly about the Bureau and its scrutiny.

Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson led the first wave of black Bureau-writers, followed by such resonant voices as Hughes, Himes, Baldwin, Baraka, Sanchez, Giovanni, Ishmael Reed and even the de-radicalizing Ralph Ellison. (A late draft of 1952’s Invisible Man, the most honored African-American novel before Toni Morrison’s 1987 Beloved, makes the protagonist a G-Man, too). In The Man Who Cried I Am (1967), an exemplary historical fiction (and chaotic anti-FBI romance) of the black 1960s, the black novelist John A. Williams proposed that “the secret to converting their change to your change was letting them know that you knew.” Many of his fellow black writers embraced Williams’ open secret and made sure to let the Bureau know that its writer-targets knew of their place in the crosshairs. This tradition of talking and spying back is typified by Richard Wright’s poem “The FB Eye Blues” (1949): “Everywhere I look, Lord / I see FB eyes / Said every place I look, Lord / I find FB eyes / I’m getting sick and tired of gover’ment spies.” Wright’s poem, composed in classic blues stanzas, moans back at a Bureau snoop whose surveillance has grown so intimate that he can repeat to Wright’s confessional speaker “all [he] dreamed last night, every word [he] said.”

Thankfully, poems, stories, plays and essays such as Wright’s have not only lived to tell of this surveillance, but also have taken their place as foundations of our country’s literary history. Even despite the brave work of African-American authors to withstand FBI eavesdropping, however, the Hoover Bureau’s shadowing of their literature is due a moment of national self-reflection.

It is not just an academic matter that U.S. state intelligence effectively arranged to jail the African-American literary tradition in the prime of the 20th century. Well before Ferguson, Baltimore or the labeling of the prison-industrial complex, the republic of black letters had joined black urban communities as a danger zone of police supervision. Over-policed books are not over-policed people, of course. All the same, the FBI’s rivalrous war with African-American writing contains lessons for our rolling crisis of police brutality—a crisis in which tweets and posts have taken the place of poems and novels, but in which black artists continue to suffer, document and transcend state surveillance as they expose how black lives matter.