TGIF POU!

The name that has come up over and over from the Cinematographers featured this week, as their mentor, is esteemed Cinematographer, Film Maker and Professor, Haile Gerima.

Haile Gerima (born March 4, 1946) is an Ethiopian filmmaker who currently lives and works Washington, DC. He is a leading member of the L.A. Rebellion film movement, also known as the Los Angeles School of Black Filmmakers. His films have received wide international acclaim. Since 1975, Gerima has also been an influential film professor at Howard University in Washington, DC. He is best known for Sankofa (1993), which won numerous international awards.

Haile Gerima was born and raised in Gondar, Ethiopia. His father was a dramatist and playwright, who traveled across the Ethiopian countryside staging local plays. He was an important early influence.

Gerima emigrated to the United States in 1968 to study theatre. He enrolled in acting classes at the Goodman School of Drama in Chicago. “When I was growing up,” he told the Los Angeles Times, “I wanted to work in theater—it never occurred to me I could be a filmmaker because I was raised on Hollywood movies that pacified me to be subservient. Film making isn’t encouraged or supported by the Ethiopian government.” He felt limited by theater and was resigned, notes Francoise Pfaff, to “subservient roles in Western plays.”

In 1970 he moved to California to attend the University of California, where he earned Bachelor’s and Master’s of Fine Arts degrees in film. He was part of a generation of new black filmmakers who became known as the Los Angeles School of Black Filmmakers, along with Charles Burnett (Killer of Sheep, Jamaa Fanaka, (Penitentiary), Ben Caldwell (I and I), Larry Clark and Julie Dash (Daughters of the Dust).

By the time Gerima graduated from UC in 1976, he had completed four films: Hour Glass (1972); Child of Resistance (1972); Bush Mama(1976); and Mirt Sost Shi Amit (also known as Harvest: 3,000 Years; 1976)

Gerima’s 1976 Bush Mama portrays the travails of Black life and culture, far removed from the drug deals and revenge killings of other black films of the era. The film is the story of Dorothy and her husband T.C., a discharged Vietnam veteran who anticipated a hero’s welcome on his return. He is arrested and imprisoned for a crime he did not commit. Theirs is a world of welfare, perennial unemployment, and despair. The film has stark black-and-white photography, but its message is moving and distinct. It addresses issues of institutionalized racism, police brutality, and poverty; these remain pertinent.

For the production of Mirt Sost Shi Amit (Harvest: 3,000 Years) Gerima returned to his native Ethiopia. It is an account of a poor peasant family who eke out an existence within a brutal, exploitative, and feudal system of labor.

His Wilmington 10—USA 10,000 (1978) explores racism and the shortcomings of the criminal justice system in the United States by examining the history of the nine Black men and one white woman who became known as the Wilmington Ten.

The travails of Black urban life in the United States are explored in the two-hour Ashes and Embers (1982), the story of a moody and disillusioned Black veteran of the Vietnam War.

After Winter: Sterling Brown (1985) is a documentary about the notable Black American poet.

Gerima is perhaps best known as the writer, producer, and director of Sankofa (1993). This historically inspired dramatic tale of African resistance to slavery won international acclaim: awarded first prize at the African Film Festival in Milan, Italy; Best Cinematography at Africa’s premier Festival of Pan African Countries (FESPACO); and nominated for the Golden Bear at the 43rd Berlin International Film Festival, where it competed with Hollywood films. The film attracted huge audiences across the United States, many of whom waited in long lines and filled theaters for weeks on end. The film subverted a notion that only mainstream distributors could attract audiences for filmmakers. Guided by an independent philosophy, Gerima practiced an innovative strategy in distribution whose success remains unprecedented in African-American film history.

The film opens with the statement: “Spirit of the dead, rise up and claim your story!” It presents a brutally realistic portrayal of African slavery. The story is revealed through the eyes of Mona, a modern-day woman who is possessed by spirits and transported to the past as Shola, a house slave on the Lafayette plantation in Louisiana. The savagery and violence of the evil institution are clearly disturbing and go far beyond the safe and conventional images of slavery presented by Hollywood. In Sankofa, we hear the chilling sound of human flesh as it is seared with a hot branding iron and see the barren faces of the human cargo; women are stripped of all dignity and subject to the continual sexual exploitation of their owners; human necks are enclosed in iron shackles; and rape is used as a tool of terror and domination. Some critics panned Gerima for excess brutality, but the Black community responded positively and enthusiastically. The film was well received and played to full houses for many weeks in major cities.

Gerima has spent his entire career resolutely avoiding the deep pockets that dominate commercial Hollywood moviemaking. He lives near Howard University, where he teaches graduate film courses, and edits his own films at Sankofa, the bookstore-cafe on Georgia Avenue that he and his wife helped establish in 1997.

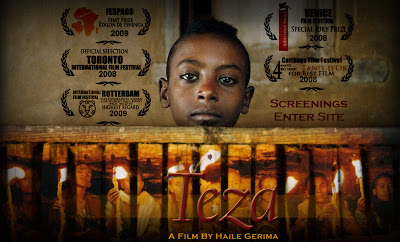

Gerima’s fiercely independent approach meant that it took him about 15 years to finish “Teza,” which had its American premiere in 2009. The movie, Gerima’s 11th, received the award for best screenplay and the Special Jury Prize at the 2008 Venice Film Festival and the highest honor at the FESPACO awards (popularly known as Africa’s Oscars).

Gerima had to secure funding for “Teza,” scout locations, get more funding, rewrite the screenplay so it could be partially set in Germany (the film has German backers), recruit non-actors to play principal roles (as he is known to do), and edit the whole thing in his offices at the cafe, where all the sandwiches are named after African and African American film directors (Spike Lee is roast beef and watercress on a panini).

All of Gerima’s films explore African or African American narratives, and many, he says, were inspired by dreams or visions. Gerima made a film about incarcerated civil rights activist Angela Davis after she appeared in one of his dreams, handcuffed, asking, “What are you going to do about it, Mr. Black Man?” And after he hallucinated in a Jamaican field at 4 a.m. and saw eyes watching him from the leaves of the sugar cane, Gerima added scenes to “Sankofa” in which field slaves stare silently from between leaves.

Gerima says he regrets the fact that most peer discussion about African cinema focuses on content rather than presentation. He describes his own films as “imperfect” and says he wishes like-minded filmmakers would be more willing to discuss the ways in which certain cinematic techniques might be improved in service of African and African American narratives.

“I try to tell them: Listen, my film is imperfect. Give me feedback, and you make me a better filmmaker,” Gerima says. “At UCLA, in the group I belonged to, feedback was the biggest part of our evolution. Without that, no one grows. But in a community with all kinds of problems, critical feedback that transforms a filmmaker becomes very minimal.”

But Gerima doesn’t regret a single one of his films.

“I know filmmaker friends who will tell me, ‘Oh, you know, I outgrew my movie.’ But I can’t. I have too much at stake in each story,” he says. “I’ve turned so many corners to make it happen.”