TGIF POU!

Today’s featured heroes all received the Medal of Honor for their actions during the Civil War.

“Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.” – Frederick Douglass

Miles James

James joined the Army in Norfolk, Virginia, and by September 30, 1864, he was serving as a Corporal in Company B of the36th Regiment U.S. Colored Troops. On that day, his unit participated in the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm in Virginia, where he was hit by a shot which mutilated his arm. Despite being urged to retreat and told that he needed immediate amputation, Miles proceeded to lead his men, firing and reloading his pistol with a single arm. Six months after the battle, on April 6, 1865, James was issued the Medal of Honor for his actions at Chaffin’s Farm. He was discharged for disability the following October.

Citation:

Having had his arm mutilated, making immediate amputation necessary, he loaded and discharged his piece with one hand and urged his men forward; this within 30 yards (27 m) of the enemy’s works.

James H. Harris (pictured below), William H. Barnes, Edward Ratcliff

Born in Saint Mary’s County, Maryland, James H. Harris worked as a farmer before joining the U.S. Army from Great Mills at age 36. He enlisted on February 14, 1864, as a private in Company B of the 38th United States Colored Troops regiment. He was promoted to corporal five months later, on July 25, and to sergeant two months after that, on September 10.

At the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm, on September 29, 1864, Harris’ regiment was among a division of black troops assigned to attack the center of the Confederate defenses at New Market Heights. The defenses consisted of two lines of abatis and one line of palisades manned by Brigadier General John Gregg’s Texas Brigade. The attack was met with intense Confederate fire; over fifty percent of the black troops were killed, captured, or wounded. The initial attack stalled at the abatis, but when a renewed effort began, Harris and two other men of the 38th USCT, Private William H. Barnes and Sergeant Edward Ratcliff, ran at the head of the assault. Being the first to breach the defenses, the three soldiers engaged the Confederates in hand-to-hand combat. They were soon joined by the remainder of their division, and the Confederate force was routed.

Here is a story from 2006 about Sergeant Edward Ratcliff (a must read!)

YORKTOWN NAVAL WEAPONS STATION — Marine Corps Cpl. Edward Radcliffe cradled the U.S. flag in his arms, holding it gently between two white-gloved hands.

He moved slowly, each step precise, across a small grassy cemetery at Yorktown Naval Weapons Station.

Then he stopped.

Sitting under a tent was his beaming 84-year-old namesake grandfather, Edward Radcliffe.![]()

The young Marine bowed down before him.

He held out the flag and solemnly whispered, “On behalf of the president of the United States, the chief of staff of the United States Army and a grateful nation, please accept this flag as a symbol of our appreciation of your grandfather’s service in the Army, for the country.”

The elder Edward Radcliffe – rarely at a loss for words – accepted the flag but could muster only a simple “Thank you” before his grandson sharply saluted, turned and marched away.

Marine Corps Cpl. Edward Radcliffe gives a U.S. flag to his grandfather – also named Edward Radcliffe – aqnd great-aunt, Marion Parker, at a ceremony Saturday honoring Civil War Medal of Honor recipient Edward Ratcliff at Yorktown Naval Weapons Station.

His eyes had welled up, as had the eyes of each of the 200 people attending this solemn celebration Saturday. They were family and friends, military and civilian, all gathered to honor yet another Edward Ratcliff, as the family name once was spelled – a man born a slave who then went on to earn a Medal of Honor fighting for the Union Army in the Civil War.

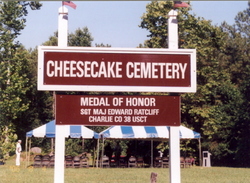

Just weeks ago, Edward Radcliffe visited this spot – the Cheesecake Cemetery – for the first time in 80 or more years. He’d come hoping to locate his grandfather’s grave.

When the War of the Rebellion entered its fourth year in 1864, the family’s version of the story goes, Edward Ratcliff left his plow standing in the field and walked from James City County to Yorktown to join the Union Army.

He left behind his wife, Grace, and daughter, Hannah, and joined the 38th Regiment of the U.S. Colored Troops.

By September 1864, Ratcliff had risen from private to first sergeant – and he found himself among thousands of other Colored Troops ordered to lead one charge on Richmond, the Confederate capital.

In the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm at New Market Heights, Ratcliff was thrown into command when the white officer leading his company was shot down. Under heavy fire, he led his men into the Confederate stronghold.

Ratcliff became the first enlisted man to enter the Confederate fortifications at this entrance to Richmond. For that, he was promoted to sergeant major and awarded the Medal of Honor – one of fewer than two dozen black soldiers to earn the military’s most prestigious award in the Civil War.

After the war, Ratcliff – now a free man – returned to his family and settled in York County, on land that today is the weapons station.![]()

He died in 1915, when he was 80.

His family, which by then included seven children and a handful of grandchildren, buried him in Cheesecake Cemetery. They marked the site with a wooden marker.

When the Navy bought the land in 1918, the cemetery became all but impossible to visit. The wooden marker deteriorated and eventually disappeared.

“For 91 years, his legacy only lived within the hearts of family and friends,” said Damon Radcliffe, Cpl. Edward Radcliffe’s brother.

“But not anymore.”

Several years ago, two amateur historians – Wes Wilson of Gloucester and Don Morfe of Baltimore – learned that Ratcliff’s grave was unmarked and began working to secure an official Medal of Honor grave marker.

Earlier this year, the men found an ally in Jim Kemp, public affairs officer at the weapons station. Kemp immediately set out to obtain an official Veterans Affairs stone and have it installed.

Navy Counselor 1st Class Jennifer O’Leary lays a wreath at the grave of Sgt. Maj. Edward Ratcliff, the first African-American to be awarded the Medal of Honor, during a ceremony at Naval Weapons Station Yorktown. In attendance were Ratcliff descendants, including his grandson, Edward Radcliffe III, who served in the Army during World War II and worked at Naval Weapons Station Yorktown for more than 32 years.

Because the exact location of Ratcliff’s grave remains unclear, Kemp had the 84-year-old grandson decide where the 295-pound granite marker should be placed.

The audience nodded in approval when Edward and his 91-year-old sister from New York, Marion Parker, unveiled the stone Saturday.

They stood tall and proud as Richmond-based re-enactors of the 38th Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops loaded their weapons and fired three volleys in salute to the Civil War soldier.

They dabbed their eyes when two re-enactors, dressed in full Civil War regalia, played taps. The somber melody echoed through the cemetery, through the trees and into the distance – each of the bugles’ notes tearing at the audience’s heartstrings.

The audience watched in silence as a Fort Eustis-based Army honor guard folded the new U.S. flag. They sobbed when Cpl. Radcliffe presented the flag to his grandfather.

Several family members mouthed the words as a harmonica played “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”:

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord;

He is tramping out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He hath loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword;

His truth is marching on.

Glory! Glory! Hallelujah!

The re-enactors lined up and marched across the cemetery, past the family. They held their heads high in respect for a man they never knew but came to honor.

Then a riderless horse was paraded by.

And with that, everyone in attendance knew that Edward Ratcliff’s legacy would never be forgotten.