Happy Friday POU

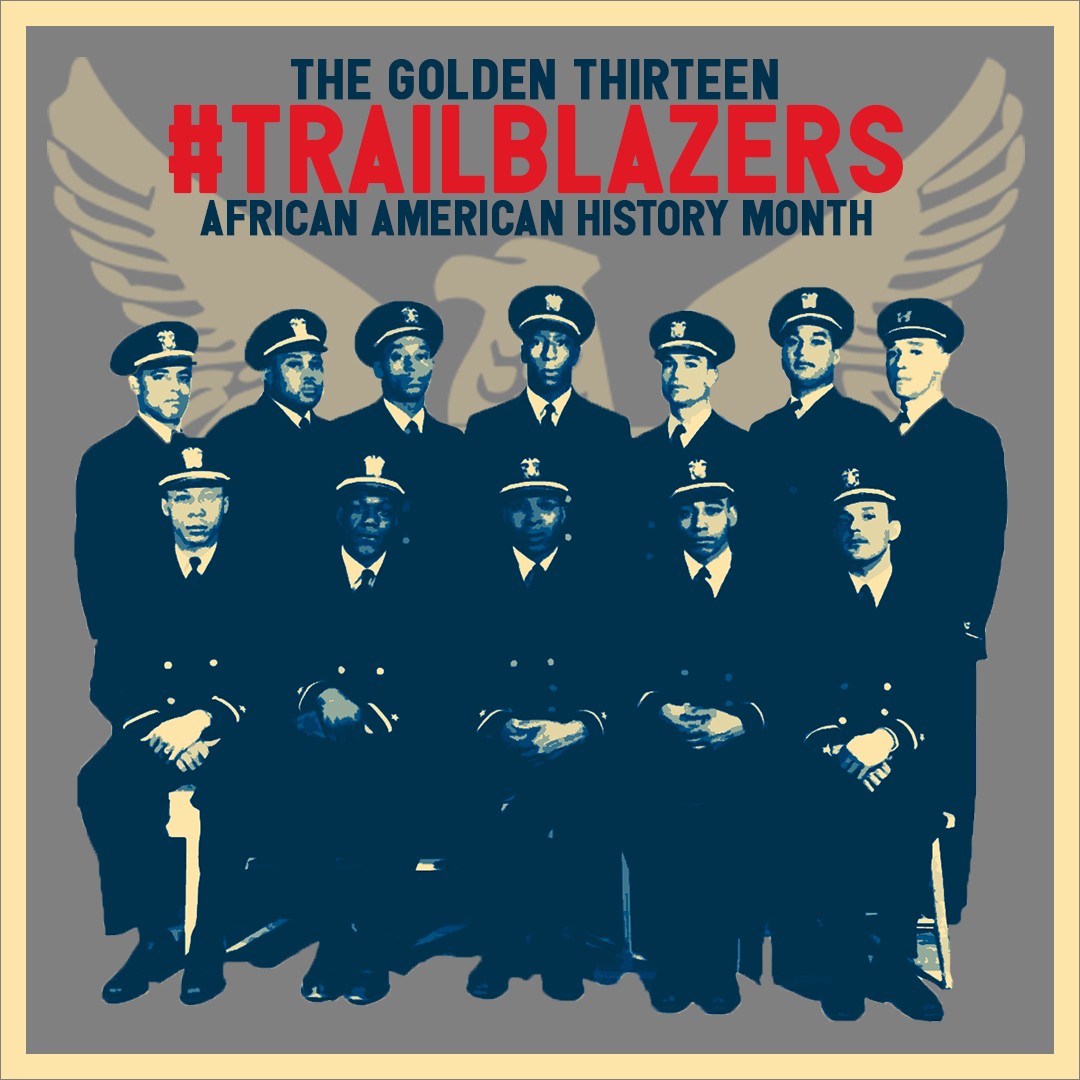

Today’s feature is all about The Golden Thirteen.

Try to imagine Navy enlisted personnel refusing to salute a Navy officer.

Yet, in 1944, a few white enlisted Navy personnel refused to salute a few Navy officers… because they were African-American.

In response to political pressure from organizations such as the National Urban League and the NAACP, the Navy commissioned its first 13 black officers in 1944. Now known and revered as the Golden Thirteen because of the gold shoulder bars worn by commissioned officers, these men were seen more often as pariahs than as pioneers more than 50 years ago. Frequently their persistence, courage and tolerance were tested.

IN 1943 the Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox, sniffed at the idea of having blacks serve as naval officers. They are perfectly happy being cooks, steward’s mates and mess attendants, he said. But pressure from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, from Eleanor Roosevelt and from Adlai Stevenson, then one of Knox’s young assistants, persuaded the Secretary to allow 13 young men to become the first black American naval officers.

The result, the Navy agreed to offer a 2-month accelerated (cram) course for officer training (at the time, normal officer training was 16 weeks). This course was to be offered to 16 black enlisted men at Camp Robert Smalls located in Illinois at the Recruit Training Center Great Lakes.

The men chosen for officer training had demonstrated top-notch leadership abilities as enlisted men. They decided early on that they were there for a reason and whatever that reason was, they were determined not to fail and they vowed “sink or swim together,” staying up late at night drilling each other on the subjects until everyone knew the material.

During their officer candidate training, they compiled a class average of 3.89, despite the demanding pace. It is a record that has yet to be broken. The Navy thought they cheated because of the high test scores. They made all of them take the test again, individually. The results were the same. Although all passed the course, only 13 were commissioned as officers.

The Navy of World War II, like virtually all American social institutions of the time, was a reflection of the racist society that produced it. One of the 13, James E. Hair, recalled having witnessed the lynching of his brother-in-law in 1935 in Fort Pierce, Fla. The society that could countenance that horror didn’t evaporate when 13 young black men were made naval officers. Because Navy policy prevented them from being assigned to combatant ships, early black officers wound up being detailed to run labor gangs ashore.

After their commissioning, they encountered white sailors who haughtily refused to salute them, and others who were blithely insulting. And they were given low-grade assignments that precluded winning honors for valor or distinguished service. One member, Mr. Graham Martin, tells the story of how he and his wife went to Chicago to eat at a downtown restaurant and laxatives were put into their food.

But the men also met whites who went out of their way to be supportive. For example, Graham E. Martin, one of the black officers, tells how he was spared a career disaster while an officer candidate at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station near Chicago. A white chief petty officer whom he was assisting at an inspection found a cigarette in the jumper pocket of a black recruit. That was against regulations. The chief petty officer told Mr. Martin to make the recruit eat it.

Mr. Martin, a graduate of Indiana University, refused on the ground that it would be harmful to the recruit’s health. Vindictively, the chief petty officer filed a report. Mr. Martin thought he was washed up. But Mr. Martin escaped punishment and certain loss of his rank when his unit commander, an Annapolis man, amused the base commander with a story about how Lord Nelson got away with violating an order by deliberately holding a telescope to his blind eye when reading a signal.

At the time the Golden Thirteen were commissioned, approximately 100,000 black Americans were listed among the enlisted ranks of the US Navy. Despite the discrimination they faced, these young men broke ground in the branch of the US Armed Forces which at the time was the most tradition-bound and segregated.

In 1977, the first of numerous reunions were organized by members of the Golden Thirteen. Some of these were even promoted by Navy recruiters.

Beginning in 1986, memories from the eight surviving members of the Golden Thirteen were collected by oral historian Paul Stillwell. In 1987, the group’s legacy was honored as the last seven living members of the group gathered at the Great Lakes Naval Recruit Training Command in Illinois to witness Building 1405 named “The Golden Thirteen.”

In 2006 (the year the last living member of the group – Ellis Sublett – died), ground was broken in North Chicago’s Veterans Memorial Park for a World War II memorial. Designed by Sutter Architects of Libertyville, it honors all veterans of the war. The memorial also contains special plaques to commemorate the Golden Thirteen, Dorie Miller, and other legendary black patriots of that war.

BLACK HISTORY: My great uncle, James E. Hair (1915-1992) was one of 13 black men who broke the Navy's color barrier by…. https://t.co/U06OqMwd2R pic.twitter.com/eWycpj81XG

— Jason Wilson (@mrjasonowilson) February 6, 2018