Good Morning POU!

Michael McCoy is a 34-year-old Baltimore resident and combat veteran who served two tours in Iraq during his five years in the United States Army. Since being medically discharged from the Army in 2008, he has been dealing with Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome. During his hospitalization at Walter Reed Hospital, he discovered documentary photography and from that moment on it has been instrumental in helping him deal with his struggle.

![]()

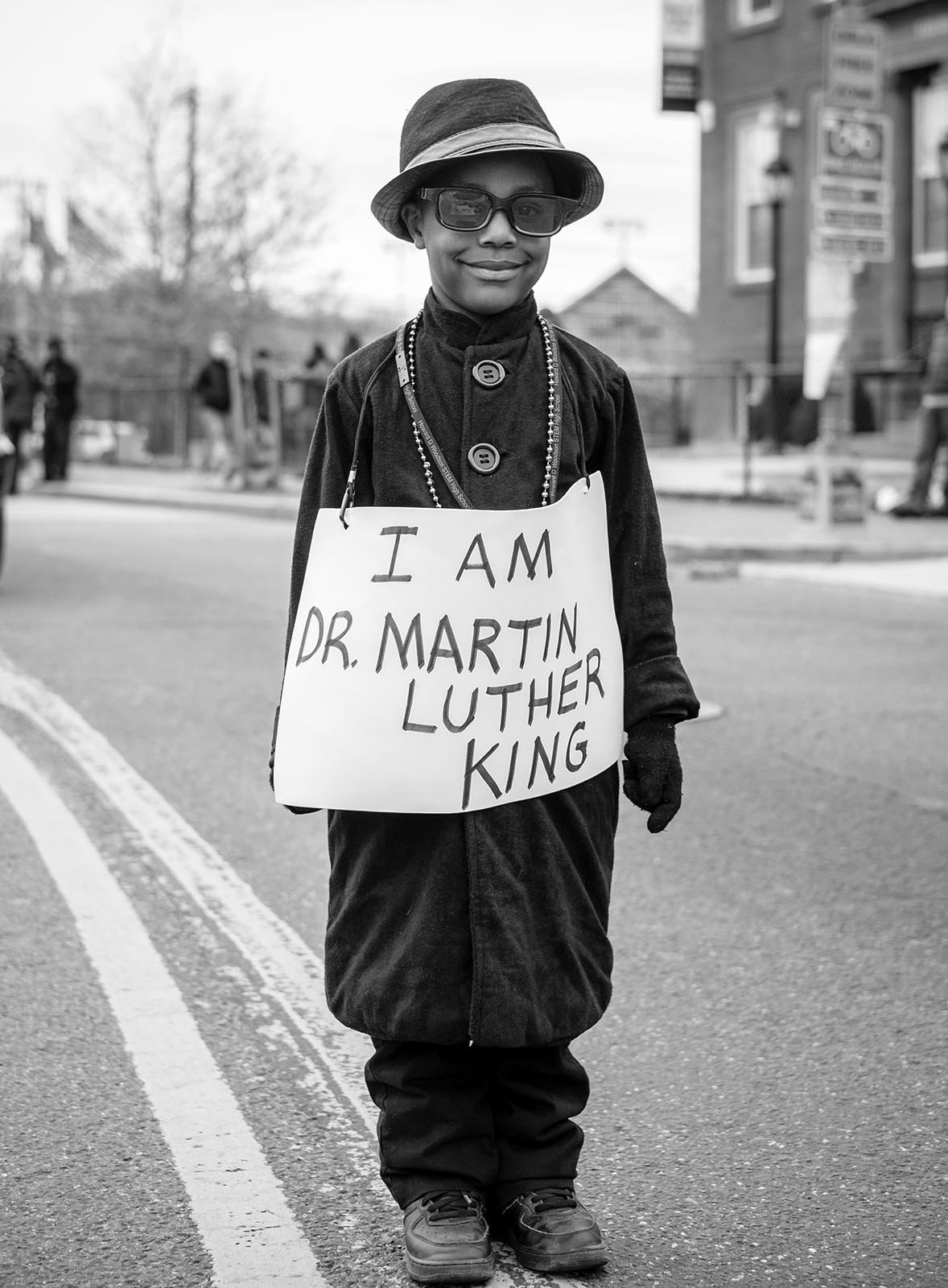

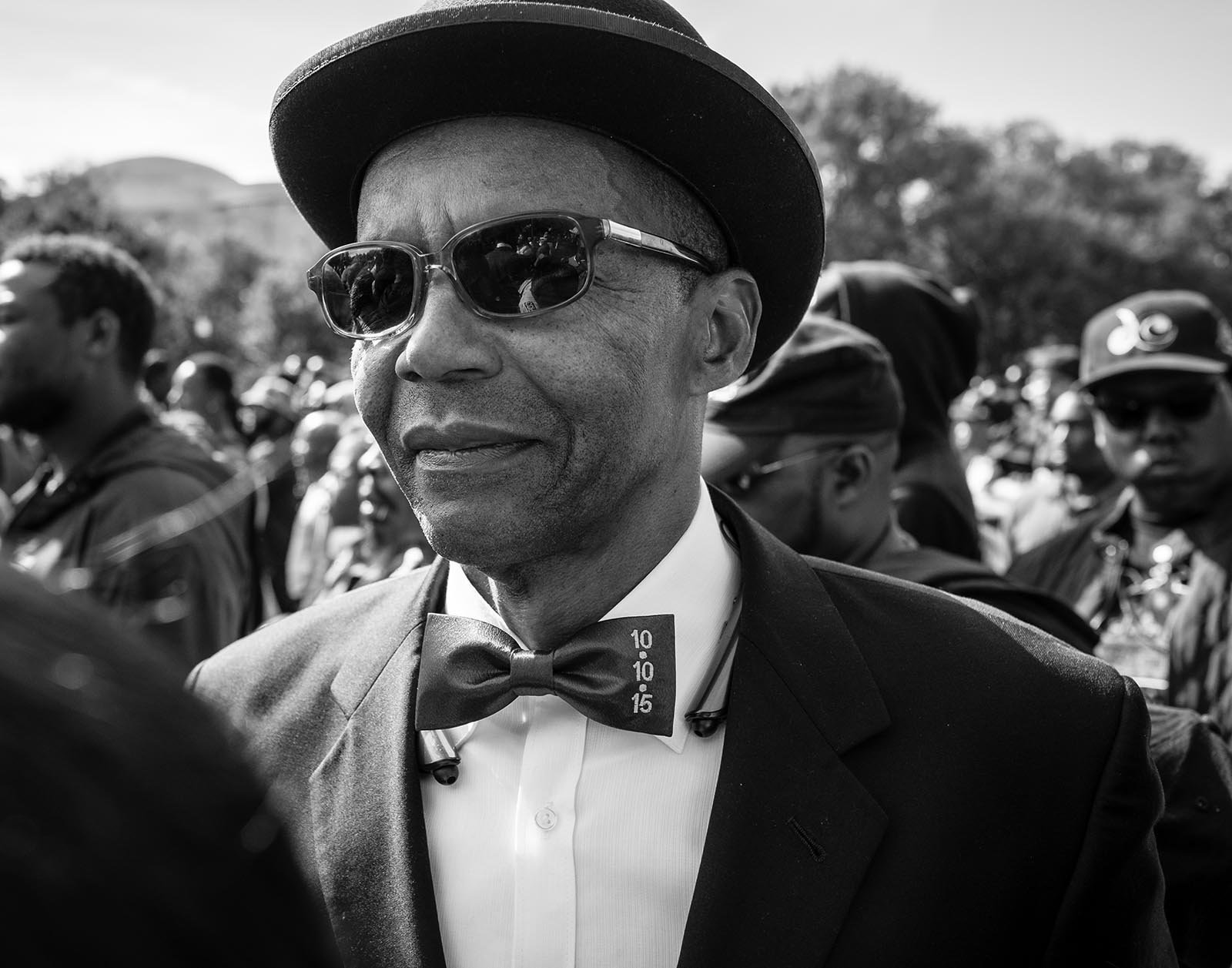

Since picking up the camera he has amassed a compelling body of work, showcasing everything from portraits, families, fathers and daughters, church services, and political protest. In addition to working as a freelance photographer, Michael is dedicated to helping veterans like himself battle PTSD using photography as a platform for both creativity and inter-communication.

(reprint from Petapixel, Feb 2017)

![]()

Michael McCoy, at age 34, has had two tours in Iraq over five years with the United States Army, and spent time at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, MD. He was medically discharged from the Army in 2008, and has been receiving treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

“During his hospitalization, he discovered documentary photography and from that moment on it has been instrumental in helping him deal with his struggle,” says artist Jamel Shabazz, one of 12 experts who was asked by Time’s LightBox to pick 12 African American Photographers You Should Follow Right Now for Black History Month. “Since picking up the camera he has amassed a compelling body of work, showcasing everything from portraits, families, fathers and daughters, church services, and political protest. In addition to working as a freelance photographer, Michael is dedicated to helping veterans like himself battle PTSD using photography as a platform for both creativity and inter-communication.”

“On my first trip to Iraq, I would take tons of pictures to keep up the morale and to send back to friends and family,” McCoy tells TIME. “I had everything backed up to a hard drive and I lost (crashed) that hard drive, which was very hurtful because I had pictures of family members that are deceased. I realized the only thing I could do was document life in the present.”

This loss inspired him to photograph present-day problems. When Freddie Gray died while in police custody in McCoy’s hometown of Baltimore, he took to the streets to capture the aftermath as the city exploded with outrage. McCoy hopes that his imagery can produce some accountability amongst the elected representatives, “and to see that all police officers, and all protesters, aren’t bad people.”

We sat down with McCoy, whose work has been displayed and talked about in newspapers and online publications the world over, to get a sense of the man behind the camera.

PetaPixel: Can you tell us a little about yourself and your background?

My name is Michael McCoy. I was born and raised in Baltimore, MD. I am a U.S Army veteran. I served almost 5 years, including 2 tours of duty to Iraq.

Joining the army was always a dream of mine as a child. My grandmother lived near an army base and whenever the soldiers would drive by, I would flag them down and they would let me play around inside of the trucks. From that moment on I knew I wanted to serve my country.

In 2013, I began serving in my church’s Photography Ministry. I attend the First Baptist Church of Glenarden, in Upper Marlboro, MD. While serving Christ, I began to see the impact and understand the importance of how photographs could change a person’s life in so many ways, such as bringing a person closer to Christ and later documenting the Black Lives Matter movement.

What did your two tours in Iraq bring to your photography?

My photography is a tool that I utilize to escape the memories experienced while serving in Iraq. I use my camera as a tool to allow my feelings from my wartime experiences, to be conveyed through the subjects I photograph.

Did your stay at Walter Reed Hospital impact your photography?

While being a patient, I have learned to be grateful that I am still alive. I also learned that we all have a story and have now found a way to share my story with others just like me.

You once had an external hard drive filled with precious memories and pictures of lost family members crash. How did that affect you?

I once owned a hard drive, on which I stored photographs that I captured during my two deployments to Iraq. I also used this hard drive to store the precious memories of my mother, who passed away during my second deployment to Iraq; also my father and my 1st cousin, both of whom have passed.

Once I realized that my data was lost and that it could not be retrieved, I felt devastated. From that moment on, I made it my purpose to always back up my data onto a backup drive and to document every moment that I could.

Since the loss of my hard drive, I’ve had the opportunity to capture and document memories such as my niece’s first Christmas, the First Baptist Church of Glenarden’s 98th Church Anniversary, U.S. Capitol Shooting, and the Bill Pickett Rodeo (an African American Rodeo) just to name a few.

Many veterans have difficulty coping with PTSD. Has photography helped you deal with yours?

It is true that many veterans have difficulties coping with PTSD. Photography allows my mind to go to a functional place, to where I can concentrate and escape the encounters of my past experiences. Photography provides me with a sense of relief and enjoyment, which rarely occurs during most of my days.

Freddie Gray died tragically at age 25 years in Baltimore, a city you call home. Did this spur your photography?

As a documentarian, it is my duty to document these social issues, to bring awareness and accountability and to hold our lawmakers and police officers accountable for their actions. I know that all police officers and citizens are not bad people, just like all people from Iraq are not bad people either.

Time magazine named you one of the “12 African American Photographers You Should Follow Right Now” last month. How did that feel?

I was extremely surprised to be acknowledged by Time magazine. From the moment that I was notified, I felt like a kid in a candy store. After reading the email, I immediately gave thanks to God for this opportunity. It was truly an honor to be recognized by Time.

Who are the photographers who have inspired you?

On your Facebook page you have quoted Gordon Parks: “The subject matter is so much more important than the photographer.” What does than mean to you in your photography?

I feel that, without the subject, the image does not have a meaning. Well before the evolution of technology and social media, photography has been a valuable storytelling tool used to bring awareness and document social issues and life, as we know it.

What was your first camera, and what equipment do you shoot with nowadays?

My first camera was a Pentax K-r with an 18-55mm kit zoom lens. I currently use the Fuji X100T, which has a 23mm f/2.0 (equiv. to 35mm) lens. I also use the Fuji X-T10 with the 23mm f/1.4 (equiv. to 35mm), 35mm f/1.4 (equiv. to 50mm), and I occasionally use my 56mm f/1.2 (equiv. to 85mm).

You have said in the past that photography is an escape for you? How so?

Whenever I place my eye at the viewfinder and my index finger onto the shutter, it allows me to escape the memories of the trauma experienced in my two deployments to Iraq. My camera provides me a sense of relief and safety.

Does the viewfinder give you a different perspective on life?

Photography has given me a different perspective on life. The camera is a tool that allows you access to things that you normally would not experience.

As a kid, I remember my dad having an old film camera. I would load the film into the camera and begin clicking away. I didn’t have a clue as to what I was doing, but it felt good. As I got older, I began to understand the importance of how much power can be produced through an image. This is why I believe that photography is an important tool.

What kind of subject matter do you like to photograph?

I like to photograph life, people.

Doing what?

But, what genre of photography do you like to shoot?

I love portrait photography and documentary photography. In portrait photography I find a fulfilling joy and comfort, because it allows me to capture special moments and emotions of people. There is no better feeling than receiving/seeing your subjects’ reaction once they have seen the end result of being photographed. One single portrait has the ability to change a person’s life.

I love documentary photography because it allows me to inform, educate, and most importantly document reality in an instant, from my perspective. Documentary photography also provides the opportunity to connect and inspire people through your vision. Most importantly documentary photography provides a platform to record history for future generations to come and it can also serve as a blueprint to create a legacy.

“It’s the not the subject that interests me as much as my perception of the subject,” Roy DeCarava. Do you agree?

Where do you see yourself headed 5 years from now?

Since the Time magazine article, I have begun to receive feedback and testimonies from other veterans who use photography to cope with PTSD. I hope to continue to use photography as a tool to inspire and educate more people living with PTSD to use photography, but importantly I would like to bring awareness and to educate others about PTSD.

Anything else you’d like to say to PetaPixel readers?

I hope this article can be a source of inspiration to all and bring more awareness to mental illness. Living with PTSD does not have a specific look. The wounds are invisible and at the end of the day the one thing that we’re looking for more than anything is love.