TGIF POU!

Who was the first black coach to lead a Division I school to the NCAA Championship?

John Thompson Jr.

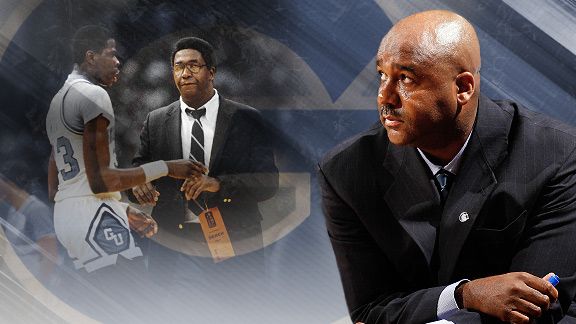

1984, thirty years ago, the men’s basketball team at Georgetown University owned March Madness. Under coach John Thompson Jr., a Washington native who’d played for the Boston Celtics, the Hoyas won their first and only NCAA title. The 1984 win, against the University of Houston, made history for another reason, too: It was the first time an African-American coach took home the trophy.

A lot has changed in the years since, including the perception of Thompson. Back then, even though he was one of the sport’s most accomplished coaches, Thompson was viewed as mysterious and intimidating. (A strained, sometimes prickly relationship with the media had something to do with that.) After his retirement in 1999, Thompson took the mic himself and hosted The John Thompson Show on ESPN 980. Over a decade-long run at the station, he became one of Washington’s most popular radio personalities. Washingtonian recently caught up with Thompson about his memories of that 1984 NCAA title, one of the most significant, yet underappreciated, accomplishments in basketball history.

Thirty years later, what memories of that championship season and game stick out to you?

What sticks out most is that you completed something every coach sets out to accomplish. In anything you do I think you are always at least making an attempt to win the championship, to be the best team that year. It is something you can’t really describe to anybody, but you feel extremely happy it happened.

You made it to three national championship games in four years and won one. What does that say about how difficult it is to win that many games in a row against good teams?

I think it’s more difficult to get to the Final Four than it is to win it. Just getting there that many times is significant. You have to win more games just to get there than just that final game to win it.

The ’84 championship game against Houston was the first time future Hall of Famers Patrick Ewing and Hakeem Olajuwon faced each other. Was there a lot of hype for that matchup going in?

How they ended their careers highlighted the Patrick vs. Hakeem matchup later more than it did at the time. Based on how their careers went on, you reflect back on how they played against each other in the championship game.

Do you feel that Ewing’s arrival took the program to another level?

We had a good team before Patrick came. Patrick came because we were good, and he made us even better. It goes without saying that just the attention and pressure he had on himself, people anticipated us winning when he came to us.

When you started recruiting Ewing, you knew you were on to something special, didn’t you?

I went to see another guy play at the Boston Garden with my assistant Bill Stein. [The other guy] was playing against Patrick’s team. Patrick was a tenth-grader. I saw Patrick play and I told Bill, “Get me him and we will win a national championship.” I was excited about his athleticism getting up and down the court and his intensity. Very rarely did you see a player of any size play with the intensity Patrick played with the entire time.

The media used the term “Hoya Paranoia” to describe the way the team and the public viewed and related to each other. What do you think about today when you hear that phrase?

I just think it’s funny. I mean, nothing comes to mind to me when I hear people say Hoya Paranoia. I think [the late Washington Post sports writer] Mark Asher was one of the first to start that. I loved Mark dearly, even though he and I fought all the time. We had order, we had rules, we had things that we did that people attributed to being paranoid, but that’s on them.

Michael Wilbon, an ESPN analyst and former Washington Post sports writer, told me he thinks there were racial undertones to some of the use of “Hoya Paranoia” and how often your team was described as intimidating.

That’s an interesting thought [laughs]. I didn’t want to be the one to initiate that thought, but if Mike Wilbon said it, it must be damn true, right? I’d rather use the word “intelligent” than “intimidating.” To play at the level we played at in the Big East, you’re not playing against Little Sisters of the Poor. You are playing against people comparable to you, so they aren’t going to be intimidated by anybody. Most good athletes would be insulted by someone saying they were intimidated. They weren’t intimidated. They were beaten.

Did you see a difference in the way you were viewed by black and white fans?

I think it’s only natural for people to be encouraging to people that are like them, if you will. It was no more than Italian-Americans pulling for Italian-American coaches in the Big East. I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing, but we had a hell of a lot of white players too. Don’t forget, as a university Georgetown probably wasn’t even 10 percent black. We had a hell of a lot of people in those stands cheering for us that weren’t black. But did it have a special connotation for black people? Sure, based on discrimination and segregation and based on lack of opportunity that people had.

When I was the first African-American to win a Division I national championship, it had a special connotation because it meant opportunities for other people. I didn’t seek approval from people. That’s where the problem was. I think people want you to permit them to validate you. That’s where your Hoya Paranoia came from, because we had rules and set goals and had procedures that suited us.

Were there a lot of misperceptions about your team?

Quite naturally—it doesn’t pertain to everybody—they thought all the kids were maybe going to be thugs or whatever the hell they wanted to think. But they are responsible for their thoughts. I didn’t engage in trying to satisfy that.

When the championship ended and you realized what you accomplished, how did you feel?

Like everybody else, I was very excited. I said, “How about the Big East now?” I was very happy. The kids deserved it, and they worked hard and they won, and that’s not always the case.

Patrick Ewing won the tournament’s Most Outstanding Player, but so many guys played well, particularly in the title game.

Patrick was very important, but he wasn’t the only important player on that team. We had a great team that played together and made sacrifices to play together. When you talk about Michael Jackson or you mention Michael Graham or David Wingate—all those guys made sacrifices to try to get there. Patrick certainly was the glue.

What did it mean to become the first African-American coach to win it?

The significance of knocking down the barrier was very important to me. Unfortunately you sometimes don’t have the right to fail when you are African-American at that time. That’s a right that should be awarded anybody who wants to reach a high-level goal. But once we won that game it was like giving the Good Housekeeping seal of approval to a lot of African-American coaches. Most of the guys were just assistant coaches, they were the guys there to bring players to these schools, but they weren’t allowed to run these teams, to coach these teams.

The fact that an African-American, whether it was me or had been anybody else, won that was significant. When a black person was in charge of something and won it, it made everybody more relieved or more comfortable and justified being able to hire whom you wanted. I’ve had several young coaches come up to me and say they appreciated me winning or something I said or did and that it created opportunities for them. I was not as conscious of that when I was younger, though I was aware of it. I felt very gratified when they said that.