TGIF POU!

Today we feature a man whose breeding knowledge practically carried the sport of horse racing into the multi-million dollar industry it is today.

The Kentucky Derby was in its infancy when Baden-Baden carried 17-year-old William Walker to victory in the late 1870s, an era when horse racing was America’s favorite pastime and jockeys were hailed as national heroes.

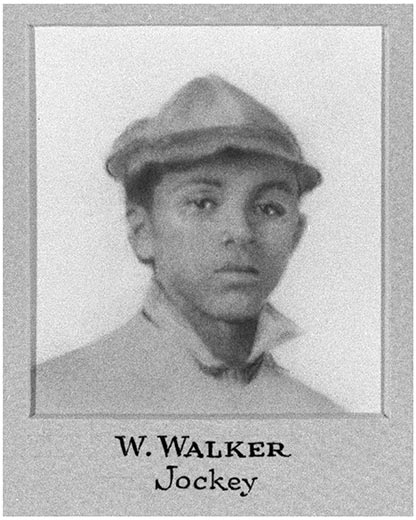

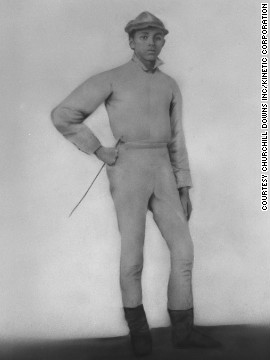

An African-American born into slavery in 1860 and only 11 when he rode his first race, Walker was an outstanding and popular jockey during a 25-year career before transitioning to another line of business, in which he enjoyed great success and influence. Upon his death at age 73 in 1933 he had arguably become the nation’s foremost pedigree expert; his encyclopedic memory was legendary in racing and breeding circles, although ultimately only footnoted or entirely ignored by many racing historians.

This year, on April 25, opening night of Churchill Downs‘ spring meeting, Walker will get some long-overdue recognition for his impact on Thoroughbred racing when he is memorialized with a stakes named in his honor.

John Asher, Churchill Downs’s vice president of racing communications, said the track has been working on ways to honor the great African-American jockeys and trainers who were such important figures in the first 30 years of the Derby—which was inaugurated in 1875—and remain a very important part of track history, the Derby, and the Kentucky Oaks (gr. I)

“The creation of a new stakes race on the opening night of Derby Week and the spring meet provided an opportunity to take a strong step in that direction, and (the track) decided to name the six-furlong sprint for 3-year-olds in honor of William Walker,” Asher said.

“While he is not a member of the trio of Derby-winning African-American riders enshrined in racing’s Hall of Fame (Isaac Murphy, Jimmy Winkfield, and Willie Simms), he touched many important segments of Kentucky’s horse industry throughout his lifetime, and he seemed an ideal choice to honor with the naming of a stakes event.”

In addition to Baden-Baden’s 1877 Derby victory, Walker was also aboard Ten Broeck the following year at Churchill in the legendary four-mile match race with the previously unbeaten California mare Molly McCarthy. The event has been immortalized in a traditional 19th century folk song, “Molly and Tenbrooks,” also known as “The Racehorse Song.”

Items from the Walker Collection, Derby History

Walker enjoyed great success at the Louisville oval. He was leading rider at six of the first 13 racing meets at Louisville Jockey Club/Churchill Downs: fall 1875, spring 1876, fall 1876, spring 1877, 1878, and 1881. Later in life he was a Daily Racing Form clocker there.

“Of all the African-American riding heroes of the Derby’s early years, Walker’s impact on Kentucky’s racing and horse industry was unlike any other and we are excited to honor his legacy and that of his contemporaries,” Asher said. “(We) felt the breadth of experience in William Walker’s career was very special for a race at this track and region.”

For Hamburg Place owner and Hall of Fame trainer John E. Madden, a shrewd horse trader and renowned for breeding five Derby winners, Walker became a trainer and trusted bloodstock adviser when his race riding days were over.

“He could trace the lineage of almost every American race horse without references,” Ben H. ‘Buck’ Weaver wrote in a December 1933 article in Turf and Sport Digest. “Walker’s knowledge of bloodlines went even deeper. Not only could he trace to taproot every Thoroughbred of consequence but… he could segregate the entire pack… according to their families.”

Walker, respectfully called “Uncle Bill,” was a familiar presence and sought-after consultant not only for Madden, himself an adviser to major owner William C. Whitney, but also for numerous wealthy would-be buyers—many high-powered financiers—at the annual Fasig-Tipton sale in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. He was handsomely compensated for his advice and by 1910 was one of Kentucky’s wealthiest African-Americans. After Madden’s death in 1929, he went alone to the sale, even though suffering from debilitating arthritis.

Famously known as the “Wizard of the Turf,” Madden bred 182 stakes winners, among them Derby winners Old Rosebud (1914), Sir Barton (1919, in partnership), Paul Jones (1920), Zev (1923), and Flying Ebony (1925) and five Belmont Stakes winners, with Sir Barton sweeping the first Triple Crown.

While no formal documentation has been found that Walker had an input into the matings that produced those classics winners and others top runners, former Kentucky Derby Museum curator and racing historian Lynn Renau said that subject is frequently discussed.

“He apparently literally had them memorized (the figure system of Thoroughbred family numbers developed in the 19th century by Australian pedigree researcher Bruce Lowe) or he had come up with a better system,” Renau said.

“He was unbelievable; he was incredible. We always admire Isaac Murphy as a jockey, but what I love about Walker is that he turns all his knowledge into becoming a consultant.”

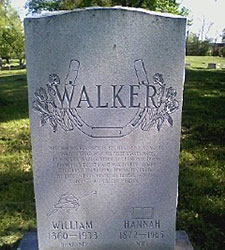

In her 1995 book Racing Around Kentucky, Renau revealed her discovery that Walker lay forgotten in an unmarked grave at Louisville Cemetery, not far from Churchill Downs.

Churchill moved quickly to rectify that the next year. Coinciding with the 100th anniversary of Walker’s final of four Kentucky Derby mounts, The Winner, who was seventh May 6, 1896, the track dedicated a four-foot high, gray granite headstone at his gravesite. An inscription outlines his racing career and features a horseshoe intertwined with roses.

Walker was born in Woodford County, Ky., the exact location unknown. Some sources say his birthplace was either at John Harper’s Nantura Farm, later the home of Ten Broeck, or Abe Buford’s Bosque Bonita Farm, upon part of which Lane’s End now sits.

Walker’s rode his first race at Jerome Park in New York and was not quite 12 when he guided in his first winner, at the Kentucky Association track in Lexington. He was 13 when he won his first stakes.

Walker participated in the first three Kentucky Derbys, finishing fourth with Bob Wooley, and then was eighth the following year with Bombay. He won with Daniel Swigert’s Baden-Baden in 1877 after tracking pacesetter Leonard from second and then dispatching the rival in the stretch, getting clear by two lengths.

Overall, Walker witnessed every Derby for 59 straight years from its 1875 debut until his death at age 73 on Sept. 20, 1933.

“Its not the Derby win, it’s what this man did to promote the breed,” said Renau, pointing out how extraordinary Walker’s accomplishments out of the saddle were. “To have just the breadth of knowledge and to convert literally from one field to another, and by the way, make money and retain wealth, to me is extremely amazing.”

Asher said he believes Walker’s credentials merit consideration to join Murphy, Winkfield, and Simms in the Hall of Fame.

“If the naming of this race in his honor shines additional light on his career and fuels conversation on the possibility of Hall of Fame enshrinement for William Walker, it will make our Churchill Downs family very happy,” he said.