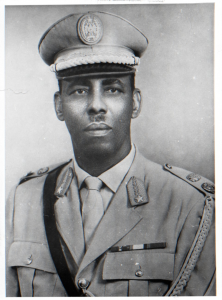

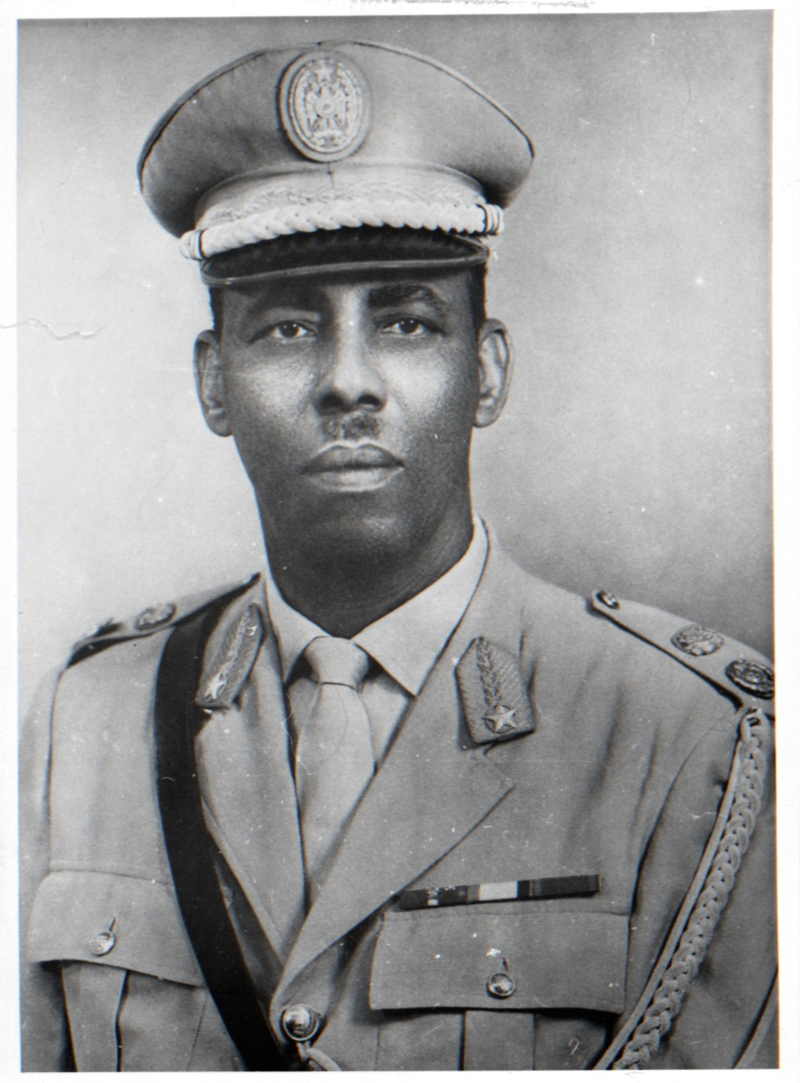

Mohamed Siad Barre (Somali: Maxamed Siyaad Barre; Arabic: محمد سياد بري; October 6, 1919 – January 2, 1995) was the President of the Somali Democratic Republic from 1969–91. During his rule, he styled himself as Jaalle Siyaad (“Comrade Siad”).

The Barre-led military junta that came to power after a coup d’état in 1969 said it would adapt scientific socialism to the needs of Somalia. Volunteer labour harvested and planted crops, and built roads, hospitals and universities . Almost all industry, banks and businesses were nationalized, and cooperative farms were promoted. A new writing system for the Somali language was also adopted. Although his government forbade clanism and stressed loyalty to the central authorities, the government was commonly referred to by the code name MOD. This acronym stood for Marehan (Siad Barre’s clan), Ogaden (the clan of Siad Barre’s mother), and Dhulbahante (the clan of Siad Barre son-in-law Colonel Ahmad Sulaymaan Abdullah, who headed the NSS). These were the three clans whose members formed the government’s inner circle. Later, President Siad Barre incited and inflamed clan rivalries to divert the attention of the public away from his increasingly unpopular regime. By the time his regime collapsed the Somali society had begun to witness an unprecedented outbreak of inter- and intra- clan conflicts.

Mohamed Siad Barre was born as a member of the Marehan Darod clan (sub-clan Rer Dini) near Shilavo in the Ogaden, Somali Region of Ethiopia. His parents died when he was ten years old.

After receiving his primary education in the town of Luuq in southern Somalia, Barre moved to Mogadishu, the capital of Italian Somaliland, to pursue his secondary education. Claiming to have been born in Garbahaareey in order to qualify, he enrolled in the Italian colonial police as a Zaptié in 1940. He later joined the colonial police force during the British military administration of Somalia, rising to the highest possible rank.

In 1950, shortly after Italian Somaliland became a United Nations Trust Territory under Italian administration, Barre attended the Carabinieri police school in Italy for two years. Upon his return to Somalia, he remained with the military and eventually became Vice Commander of Somalia’s Army when the country gained its independence in 1960. After spending time with Soviet officers in joint training exercises in the early 1960’s, Barre became an advocate of Soviet-style Marxist government. He believed in a socialist government, and a stronger sense of nationalism.

In 1969, following the assassination of Somalia’s second president, Abdirashid Ali Shermarke, the military staged a coup on October 21 (the day after Shermarke’s funeral), and took over office. The Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) that assumed power was led by Major General Barre, Lieutenant Colonel Salaad Gabeyre Kediye and Chief of PoliceJama Korshel. Kediye officially held the title of “Father of the Revolution,” and Barre shortly afterwards became the head of the SRC. The SRC subsequently renamed the country the Somali Democratic Republic, arrested members of the former government, banned political parties, dissolved the parliament and the Supreme Court, and suspended the constitution.

Styled the “Victorious Leader” (Guulwade), Siad Barre fostered the growth of a personality cult. Portraits of him in the company of Marxand Lenin lined the streets on public occasions. He advocated a form of scientific socialism based on the Qur’an and Marx, with heavy influences of Somali nationalism.

In July 1976, Barre’s SRC disbanded itself and established in its place the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (SRSP), a one-party government based on scientific socialism and Islamic tenets. The SRSP was an attempt to reconcile the official state ideology with the official state religion by adapting Marxist precepts to local circumstances. Emphasis was placed on the Muslim principles of social progress, equality and justice, which the government argued formed the core of scientific socialism and its own accent on self-sufficiency, public participation and popular control, as well as direct ownership of the means of production. While the SRSP encouraged private investment on a limited scale, the administration’s overall direction was essentially communist.

A new constitution was promulgated in 1979 under which elections for a People’s Assembly were held. However, Barre’s Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party politburo continued to rule. In October 1980, the SRSP was disbanded, and the Supreme Revolutionary Council was re-established in its place.

One of the first and principal objectives of the revolutionary regime was the adoption of a standard national writing system. Shortly after coming to power, Barre introduced the Somali language (Af Soomaali) as the official language of education, and selected the modified Latin script developed by the Somali linguist Shire Jama Ahmed as the nation’s standard orthography. From then on, all education in government schools had to be conducted in Somali, and in 1972, all government employees were ordered to learn to read and write Somali within six months. The reason given for this was to decrease a growing rift between those who spoke the colonial languages, and those who did not, as many of the high ranking positions in the former government were given to people who spoke either Italian or English.Additionally, Barre also sought to eradicate the importance of clan affiliation within government and civil society.

Barre advocated the concept of a Greater Somalia , which refers to those regions in the Horn of Africa in which ethnic Somalis reside and have historically represented the predominant population. Greater Somalia thus encompasses Somalia, the republic of Djibouti, the Ogaden (in modern-day Ethiopia) and the North Eastern Province (in Kenya) i.e. the almost exclusively Somali-inhabited regions of the Horn of Africa. In July 1977, the Ogaden War broke out after the government sought to incorporate the various Somali-inhabited territories of the region into a Greater Somalia. The Somali national army invaded the Ogaden and was successful at first, capturing most of the territory.

Between 1974 and 1975, a major drought referred to as the Abaartii Dabadheer (“The Lingering Drought”) occurred in the northern regions of Somalia. The Soviet Union, which at the time maintained strategic relations with the Barre government, airlifted some 90,000 people from the devastated regions of Hobyo and Caynaba. New settlements of small villages were created in the Jubbada Hoose (Lower Jubba) and Jubbada Dhexe (Middle Jubba) regions. These new settlements were known as the Danwadaagaha or “Collective Settlements”. The transplanted families were introduced to farming and fishing, a change from their traditional pastoralist lifestyle of livestock herding. Other such resettlement programs were also introduced as part of Barre’s effort to undercut clan solidarity by dispersing nomads and moving them away from clan-controlled land.

By the mid-to-late-1970’s, public discontent with the Barre regime was increasing, largely due to corruption among government officials as well as poor economic performance. The Ogaden War had also weakened the Somali army substantially and military spending had crippled the economy. Foreign debt increased faster than export earnings, and by the end of the decade, Somalia’s debt of 4 billion shillings equaled the earnings from seventy-five years’ worth of banana exports. Barre faced a shrinking popularity and increased domestic resistance. In response, Barre’s elite unit, the Red Berets (Duub Cas), and the paramilitary unit called the Victory Pioneers carried out systematic terror against the Majeerteen, Hawiye, and Isaaq clans. The Red Berets systematically smashed water reservoirs to deny water to the Majeerteen and Isaaq clans and their herds. More than 2,000 members of the Majeerteen clan died of thirst, and an estimated 5,000 Isaaq were killed by the government. Members of the Victory Pioneers also raped large numbers of Majeerteen and Isaaq women, and more than 300,000 Isaaq members fled to Ethiopia.

By 1978, manufactured goods exports were almost non-existent, and with the lost support of the Soviet Union the Barre government signed a structural adjustment agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) during the early 1980’s. This included the abolishment of some government monopolies and increased public investment. This and a second agreement were both cancelled by the mid-1980’s, as the Somali army refused to accept a proposed 60 percent cut in military spending. New agreements were made with the Paris Club, the International Development Association and the IMF during the second half of the 1980’s. This ultimately failed to improve the economy which deteriorated rapidly in 1989 and 1990, and resulted in nationwide commodity shortages.

Part of Barre’s time in power was characterized by oppressive dictatorial rule, including persecution, jailing and torture of political opponents and dissidents. The United Nations Development Program stated that “the 21-year regime of Siyad Barre had one of the worst human rights records in Africa.” In January 1990, the Africa Watch Committee, a branch of Human Rights Watch organizational released an extensive report titled “Somalia A Government At War with Its Own People” composing of 268 pages, the report highlights the widespread violations of basic human rights in the northern regions of Somalia. The report includes testimonies about the killing and conflict in northern Somalia by newly arrived refuges in various countries around the world. Systematic human rights abuses against the dominant Isaaq clan in the north was described in the report as “state sponsored terrorism” “both the urban population and nomads living in the countryside were subjected to summary killings, arbitrary arrest, detention in squalid conditions, torture, rape, crippling constraints on freedom of movement and expression and a pattern of psychological intimidation. The report estimates that 50,000 to 60,000 people were killed from 1988 to 1989.” Amnesty International went on to report that torture methods committed by Barre’s National Security Service (NSS) included executions and “beatings while tied in a contorted position, electric shocks, rape of woman prisoners, simulated executions and death threats.”

After fallout from the unsuccessful Ogaden campaign, Barre’s administration began arresting government and military officials under suspicion of participation in an abortive 1978 coup d’état. Most of the people who had allegedly helped plot the putsch were summarily executed. However, several officials managed to escape abroad and started to form the first of various dissident groups dedicated to ousting Barre’s regime by force.

By the mid-1980’s, more resistance movements supported by Ethiopia’s communist Derg administration had sprung up across the country. Barre responded by ordering punitive measures against those he perceived as locally supporting the guerillas, especially in the northern regions. The clampdown included bombing of cities, with the northwestern administrative center of Hargeisa, a Somali National Movement (SNM) stronghold, among the targeted areas in 1988. The bombardment was led by General Mohammed Said Hersi Morgan, Barre’s son-in-law, and resulted in the deaths of 50,000 people in the north.

After fleeing Mogadishu in January 1991, Barre temporarily remained in the southwestern Gedo region of the country, which was the power base of his Marehan clan. From there, he launched a military campaign to return to power. He twice attempted to retake Mogadishu, but in May 1991 was overwhelmed by General Mohamed Farrah Aidid’s army, and was forced into exile.

Barre initially moved to Nairobi, Kenya, but opposition groups with a presence there protested his arrival and support of him by the Kenyan government. In response to the pressure and hostilities, he moved two weeks later to Nigeria. Barre died on January 2, 1995 in Lagos from a heart attack. He was buried in the Garbahaareey district of the Gedo region in Somalia.