TGIF POU!

We continue our series on the actions of black athletes against social and political injustices.

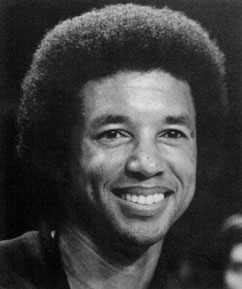

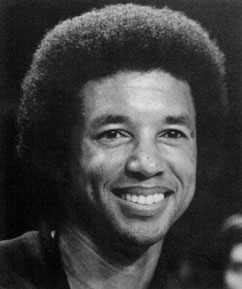

Today we feature the legendary Arthur Ashe.

“After he contracted the AIDS virus he was asked, ‘Is this the hardest thing you’ve ever had to deal with?’ And he said, ‘No, the hardest thing I’ve ever had to deal with is being a black man in this society,” Journalist Ralph Wiley about Arthur Ashe on ESPN Classic’s SportsCentury series.

Arthur Ashe’s brilliant career as a professional tennis player in no way truly reflect the greatness of the man. His activism off the courts have inspired and paved the way for so many others beyond the world of tennis.

First, just a refresher of what he did within the sport:

Upon graduating from high school first in his class, Arthur went to UCLA, which had one of the best college tennis programs. That year he was also named to the U.S. Davis Cup team as its first African-American player. In 1965 he won the individual NCAA championship.

Following college Arthur served his country, joining the U.S. Army from 1966-68. While stationed at West Point in New York, he eventually reached the rank of second lieutenant. During his time in the army he continued to play tennis, participating in the Davis Cup and other tournaments. Still an amateur, Arthur triumphed over Tom Okker of the Netherlands on September 9, 1968 to win the first U.S. Open. Unfortunately, because of his amateur status he could not accept the prize money, which was given to Okker despite his loss. He is the only African-American man to ever win the title.

In January of 1970 Arthur won the Australian open, the second of his three career grand Slam singles titles. By the early 70s he had become one of the most famous tennis players. Along with Arthur’s growing celebrity status, the sport of tennis was becoming more and more popular. However, the earnings of tennis players did not reflect the increased interest and therefore revenue. In response to this he partnered in creating the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) in 1972 with Jack Kramer and others. The ATP was formed to represent the interests of male tennis pros. Prior to its formation players had less control over their earnings or their tournament schedule. Two years later he was elected as the President of ATP.

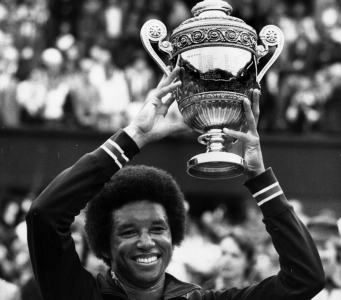

In 1973, He was the first black pro to play in the national championships in South Africa where he reached the singles finals and won the doubles title with Tom Okker. On July 5, 1975 he defeated the heavily favored Jimmy Connors in four sets to win the Wimbledon singles title. He was the first and only black man to win the most prestigious grass-court tournament. He also attained the #1 men’s ranking in the world.

In 1979 Arthur suffered a heart attack while holding a tennis clinic in New York. He was hospitalized for ten days afterwards and later that year underwent quadruple-bypass surgery. He continued to suffer chest pains though and in 1980 decided to retire from tennis with a career record of 818 wins, 260 losses and 51 titles.

He continued to keep applying for visas, and the country continued to deny him. In protest he used this example of discrimination to campaign for the expulsion of the nation from the International Lawn Tennis Federation. This was the beginning of his activism against Apartheid, which would become a central issue to him for the next two decades. It wasn’t until 1973 that the South African government granted the visa that led to him becoming the first black pro to play in the South African Open.

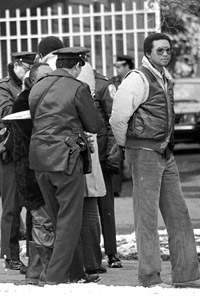

He remained focused on South Africa and in 1983 co-chaired the committee Artists and Athletes Against Apartheid with Harry Belafonte. Arthur was arrested numerous times protesting against the brutal practice of apartheid.

In 1990, President F. W. de Klerk reversed the government position on apartheid, releasing Nelson Mandela, who had been imprisoned for 27 years because of his anti-apartheid activism, and legalizing anti-apartheid political groups. When Mandela was released, one of the first people he asked to meet was Arthur Ashe.

In 1992, Ashe was arrested in front of the White House protesting the expulsion of Haitian refugees by the Bush Administration. Ashe wore a T-shirt distributed by the NAACP, which read “Locked Out Because They’re Black.”

In 1992 the newspaper USA Today contacted him about reports of his illness. Ashe had discovered in 1988, that a transfusion during his second bypass surgery, had resulted in him contracting HIV. Arthur decided to preempt the paper and go public on his own terms holding a press conference with his wife on April 8, 1992 to announce that he had contracted AIDS. This incited a whirlwind of publicity and attention, which Arthur used to raise awareness about AIDS and its victims. In his memoir “Days of Grace” he wrote, “I do not like being the personification of a problem, much less a problem involving a killer disease, but I know I must seize these opportunities to spread the word.”

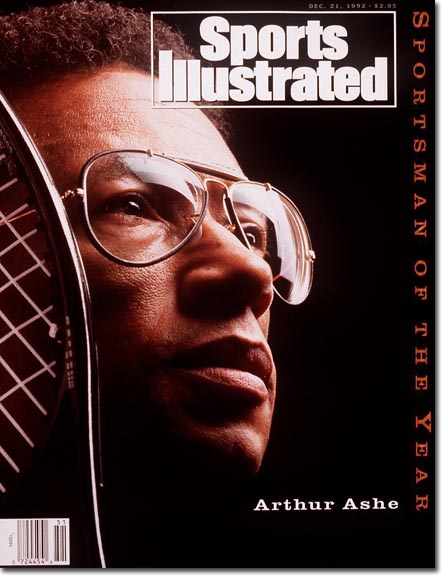

In the last year of his life he founded the Arthur Ashe Foundation for the Defeat of AIDS, which raised money for research into treating, curing and preventing AIDS, the end goal being the eradication of the disease. He also spoke before the U.N. General Assembly on World AIDS day imploring the delegates to increase funding for AIDS research and discussing the need to address AIDS as a world issue, anticipating the global spread of the disease in the coming years. That year Arthur Ashe was named Sports Illustrated’s Sportsman of the Year, an honor bestowed upon “the athlete or team whose performance that year most embodies the spirit of sportsmanship and achievement,” undoubtedly due to his incessant work and indefatigable spirit.

Two months before his death he founded the Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health, to help address issues of inadequate health care delivery to urban minority populations. He also dedicated time in his last few months to writing “Days of Grace,” his memoir that he finished only days before his death.

On February 6, 1993 Arthur Ashe died of AIDS-related pneumonia in New York at the age of 49. His body was laid in state at the Governor’s Mansion in his hometown of Richmond, VA. He was the first person to lie in state at the mansion since the Confederate general Stonewall Jackson in 1863.

On what would have been Arthur’s 53rd birthday, July 10, 1996, a statue of him was dedicated on Richmond’s Monument Avenue. Before this, Monument Avenue had commemorated Confederate war heroes; in fact, as a child Arthur would not even have been able to visit Monument Avenue because of the color of his skin. Arthur is depicted carrying books in one hand and a tennis racket in the other, symbolizing his love of knowledge and tennis. In 1997 the USTA announced that the new center stadium at the USTA National Tennis Center would be named Arthur Ashe Stadium, commemorating the life of the first U.S. Open men’s champion in the place where all future U.S. Open champions will be determined.