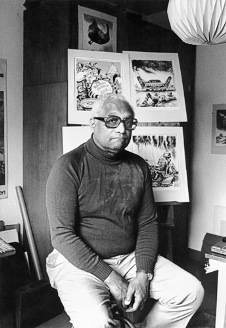

Oliver Wendell Harrington was born on February 14, 1912, in Valhalla, NY, the son of an African-American father and a Jewish mother from Budapest. Growing up in the South Bronx, an ethnically diverse neighborhood, Harrington was early on sensitized to racism in American society. From the beginning of his artistic career in 1929, he drew cartoons not only to establish a more realistic and less stereotypical depiction of African-American life but also to vent his anger about the continuing racial discrimination in the U.S.

Oliver Wendell Harrington was born on February 14, 1912, in Valhalla, NY, the son of an African-American father and a Jewish mother from Budapest. Growing up in the South Bronx, an ethnically diverse neighborhood, Harrington was early on sensitized to racism in American society. From the beginning of his artistic career in 1929, he drew cartoons not only to establish a more realistic and less stereotypical depiction of African-American life but also to vent his anger about the continuing racial discrimination in the U.S.

During the 1930s, Harrington lived and worked as a freelance artist in Harlem, which was still flourishing in the afterglow of the Harlem Renaissance. In Harlem, he became part of a thriving community of black artists, among them the famous African-American poet Langston Hughes, with whom he developed a lifelong friendship. In 1935, Harrington began a satirical and often political cartoon in the Amsterdam News entitled “Dark Laughter” which recorded the absurdities and frustrations of Harlem life.

In this context, he developed his best-known cartoon character: Bootsie, an ordinary African-American man coping with everyday racism in American society. Langston Hughes honored his friend’s work when he wrote the introduction for the 1958 anthology Bootsie and Others: A Selection of Cartoons by Ollie Harrington.

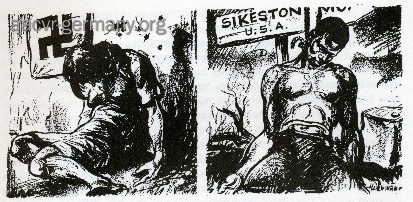

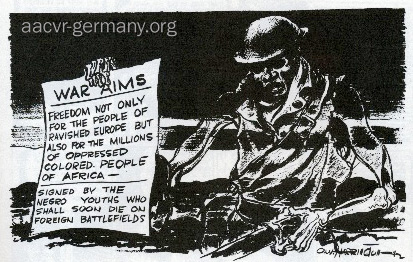

It was in his artistic work during World War II that Harrington exposed the discrepancy between the U.S fight for democracy abroad and the status of African Americans as second-class citizens at home. He questioned the U.S. policy of fighting fascism and racism in Europe while tolerating the racism of European colonial powers in other parts of the world. In his cartoons, Harrington thus chose to illustrate uncomfortable questions by insisting that victory in World War II would also mean that America had to rethink its own system of racial segregation and discrimination.

It was in his artistic work during World War II that Harrington exposed the discrepancy between the U.S fight for democracy abroad and the status of African Americans as second-class citizens at home. He questioned the U.S. policy of fighting fascism and racism in Europe while tolerating the racism of European colonial powers in other parts of the world. In his cartoons, Harrington thus chose to illustrate uncomfortable questions by insisting that victory in World War II would also mean that America had to rethink its own system of racial segregation and discrimination.

After the war – moved by a wave of brutal lynchings of returning veterans in the South – Harrington accepted Walter White’s proposal to organize the NAACP’s Public Relations Department from which he was able to advocate an end to racial discrimination. In 1946, he explained that he had taken on this struggle because black soldiers had fought “to tear down the sign ‘No Jews Allowed’ in Germany” only to find that “the sign, ‘No Negroes Allowed’” was still there when they returned to their homes.

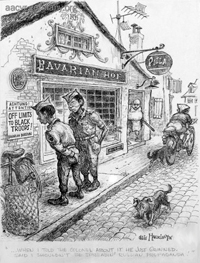

His political activism on behalf of civil rights brought him to the attention of McCarthy-era witch-hunters. As a result, Harrington left the United States in 1951 and settled in France, where he became part of an active African-American expatriate community, befriending writers such as James Baldwin, Richard Wright, and William Gardner Smith.

In East Germany, Harrington enjoyed particularly high esteem for his skills as a political cartoonist and specialized in addressing the political situation in America and the world at large, giving frequent attention to racism, poverty, and imperialism.

In East Germany, Harrington enjoyed particularly high esteem for his skills as a political cartoonist and specialized in addressing the political situation in America and the world at large, giving frequent attention to racism, poverty, and imperialism.

Both the humor magazine Eulenspiegel and the general interest periodical Das Magazin, one of the most popular papers in East Germany, used his art work on a regular basis. Throughout his life, Harrington remained a keen observer and denouncer of institutionalized racial injustice.