John Chaney is a retired basketball coach who is best known for his twenty-four-year career as the head coach at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Raised in poverty during an era of legally sanctioned racism, Chaney earned his college education through his athletic skill. He became a firm believer in the importance of education for young people who wished to improve their lives. As a coach, whether at the junior high, high school, or university level, Chaney worked hard to provide leadership and guidance to the young men who played on his teams. As a teenager in the working-class neighborhood of South Philly, Chaney began playing basketball, first in pickup street games, where he played against future greats such as Wilt Chamberlain, then on the varsity team at Benjamin Franklin High School. His high school coach, Sam Browne, became another important mentor in Chaney’s life, guiding him through an outstanding high school career that culminated in a Most Valuable Player title in 1951 in the Philadelphia Public League.

Chaney’s stellar basketball career continued in college. A powerhouse guard, he scored a record 57 points in one game and helped Bethune-Cookman win the 1953 Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference tournament. That same year he was named all-American by the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics. Along with his athletic achievements, he also learned essential lessons about the importance of academics.

After Chaney graduated from Bethune-Cookman in 1955, he hoped, like many star college athletes, to earn his living by playing ball. Since the National Basketball Association (NBA) did not hire African-American players, he sought work with other teams. For a short time he played with the Harlem Globetrotters. Chaney was paid by the game, with his salary often depending on how many tickets were sold to spectators. He played for Eastern League teams for nearly ten years, earning most valuable player awards in 1959 and 1960.

Chaney’s career on the court came to an abrupt end during the early 1960s when he injured his knee in an automobile accident. Unable to play basketball, he took a job teaching physical education and coaching basketball at Phildelphia’s Sayre Junior High School. After coaching his team to fifty-nine wins out of sixty-eight games at Sayre, he moved to Simon Gratz High School, also in Philadelphia, where he served as health and physical education teacher as well as dean of boys. He continued to coach basketball at Simon Gratz, greatly improving that team’s win record as well.

Chaney’s coaching success caught the attention of the athletic department of Cheyney State College (now Cheyney University of Pennsylvania) a historically black college in the suburbs of Philadelphia. In 1972 the school hired Chaney as head basketball coach. He remained at Cheyney State for ten years, taking the Cheyney Wolves to the 1978 Division II championship and amassing 225 wins and only 59 losses during his coaching career there.

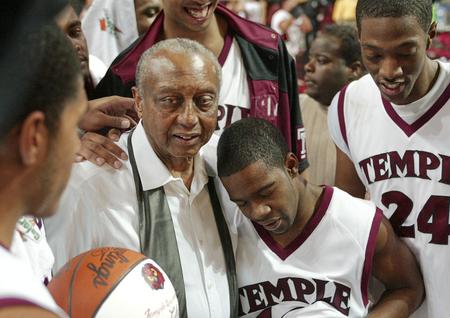

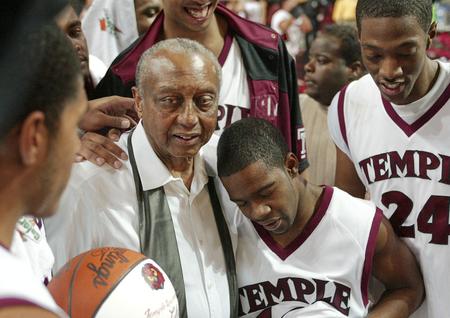

In 1982 Philadelphia’s Temple University approached Chaney with a job offer. Noting his ability to coach teams to winning records, the school hired him as head coach in hopes that he could build a nationally competitive basketball team at Temple. For the next twenty-four years, Chaney remained at Temple, coaching the team through seventeen National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) tournaments and five NCAA regional finals. Chaney fulfilled his promise to make Temple a national contender, but his contribution to his team went far beyond his win-loss record, and he taught his players much more than the drills and plays that would improve their game.

Having grown up under the disadvantages of a broken home, poverty, and racism, Chaney understood the problems facing his players, many of whom were scholarship students from similar backgrounds. He became a father figure and mentor to his team members as well as coach and teacher, and he taught his players the self-discipline and commitment that he believed they needed to succeed in the world beyond basketball.

Chaney’s team practices began at 5:30 am so that his players would have time to study and attend all their classes, and he made it clear that education should never come second to sport. “They just want to bounce the ball and dribble the ball, but I talk about things that are going to stay with them for the rest of their lives,” Chaney said during a press conference reported on the ESPN Web site. “Somewhere along the line, it will reverberate and they’ll remember it.”