Civil Rights activism predates the Civil Rights Movement by more than a century.

Most people know that Northern states such as New York allowed slavery for a time and then abolished it. What many don’t realize is that before the South adopted Jim Crow, the North had it, virtually everywhere, and that a lot of courageous now mostly nameless and faceless black folks fought it.

Elizabeth Jennings Graham was another one. Her 1854 defiance of a streetcar conductor’s order to leave his car helped desegregate public transit in New York City. Her story is below.

We also fought segregated schools. According to the Library of Congress exhibit With an Even Hand: “Benjamin Roberts, a black printer, filed a lawsuit against the city of Boston to integrate public schools. In 1849, reformer and future U.S. Senator Charles Sumner represented Roberts and challenged school segregation in the Boston court,” but the court upheld segregation.

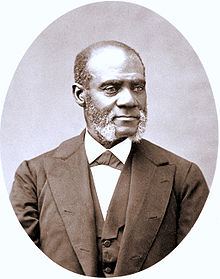

Henry Highland Garnet was one of them. He helped found the New York Association for the Political Elevation and Improvement of People of Color in 1838. Sounds a lot like the NAACP doesn’t it? Because it was. They fought the property qualifications that New York imposed on black voters alone in 1821.

Henry Highland Garnet (December 23, 1815 – February 13, 1882) was an African-American abolitionist, minister, educator and orator. An advocate of militant abolitionism, Garnet was a prominent member of the movement that led beyond moral suasion toward more political action. Renowned for his skills as a public speaker, he urged blacks to take action and claim their own destinies. For a period, he supported emigration of American free blacks to Mexico, Liberia or the West Indies, but the American Civil War ended that effort.

Henry Garnet was born into slavery in New Market, Frederick County, Maryland, on December 23, 1815. According to James McCune Smith, Garnet’s father was George Trusty and his mother was a woman of “extraordinary energy.” In 1824, the family, which included a total of 11 members, secured permission to attend a funeral, and from there, they all escaped in a covered wagon, first to Wilmington, Delaware, and then to New York City. Garnet attended the African Free School, and the Phoenix High School for Colored Youth. While in school, Garnet began his career in abolitionism. With fellow schoolmates, he established the Garrison Literary and Benevolent Association. It garnered mass support among whites, but the club ultimately had to move due to racist feelings. Two years later, in 1835, he started studies at the Noyes Academy in Canaan, New Hampshire.

Due to his abolitionist activities, Henry Garnet was driven away from the Noyes Academy by an angry segregationist mob. He completed his education at the Oneida Theological Institute in Whitesboro, New York, which had recently admitted all races. Here he was acclaimed for his wit, brilliance, and rhetorical skills. After graduation in 1839, the following year he injured his knee playing sports. It never recovered, and his lower leg had to be amputated in 1839.

Garnet married Julia Williams, whom he had met as a fellow student at the Noyes Academy. Together they had three children, only one of whom survived to adulthood.

In 1839, Garnet moved with his family to Troy, New York, where he taught school and studied theology. In 1842, Garnet became pastor of the Liberty Street Presbyterian church, a position he held for six years. During this time, he published papers that combined both religious and abolitionist themes. Closely identifying with the church, Garnet supported the temperance movement and became a strong advocate of political antislavery.

He later returned to New York City, where he joined the American Anti-Slavery Society and frequently spoke at abolitionist conferences. One of his most famous speeches, “Call to Rebellion,” was delivered August 1843 to the National Negro Convention in Buffalo, New York. Garnet said that slaves should act for themselves to achieve total emancipation. He promoted an armed rebellion as the most effective way to end slavery. Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, along with many other abolitionists both black and white, thought Garnet’s ideas were too radical and could damage the cause by arousing too much fear and resistance among whites. Garnet supported the Liberty Party, a party of reform that was eventually absorbed into the Republican Party. Garnet disagreed with the later Republicans.

By 1849 Garnet began to support emigration of blacks to Mexico, Liberia, or the West Indies, where he thought they would have more opportunities. In support of this, he founded the African Civilization Society. Similar to the British African Aid society, it sought to establish a West African colony in Yoruba (present-day Nigeria). Garnet advocated a kind of black nationalism in the United States, which included establishing separate sections of the nation to be black colonies.

In 1850, he went to Great Britain at the invitation of the Free Labor Movement, which opposed slavery by rejecting the use of products produced by slave labor. He was a popular lecturer, and spent two and a half years lecturing. In 1852 Garnet was sent to Kingston, Jamaica, as a missionary. He spent three years there, until his health forced him back to the United States.

When the American Civil War started, Garnet’s hopes ended for emigration as a solution for American blacks. He worked to found black army units to aid the Union cause. In the three-day New York draft riots of July 1863, mobs attacked blacks and black-owned buildings. Garnet and his family escaped attack when his daughter quickly chopped their nameplate off their door before the mobs found them.

When the federal government approved creating black units, Garnet helped with recruiting United States Colored Troops. He moved with his family to Washington, DC so that he could support the black soldiers and the war effort. He preached to many of them while serving as pastor of the Liberty (Fifteenth) Street Presbyterian Church from 1864 until 1866. During this time, he was the first black minister to preach to the House of Representatives, addressing them on February 12, 1865 about the end of slavery .

Garnet’s last wish was to go to Liberia to live, even for a few weeks, and to die there. He was appointed as the U.S. Minister to Liberia in late 1881, and died in Africa two months later. Garnet was given a state funeral by the Liberian government and was buried at Palm Grove Cemetery in Monrovia. Frederick Douglass, who had not been on speaking terms with Garnet for many years because of their differences, still mourned Garnet’s passing and noted his achievements.

Elizabeth Jennings Graham according to her death certificate she was born in 1826, but an 1850 census shows that she could have been born in 1830. The actual date of birth was never found. Elizabeth Jennings Graham was an African-American teacher and church organist; as a young woman, she became noted as a 19th-century civil rights figure after insisting on her right to ride on an available New York City streetcar in 1854, at a time when all such companies were private and most operated segregated cars. Her case was decided in her favor in 1855, and it led to the eventual desegregation of all New York City transit systems by 1865.

Elizabeth Jennings Graham according to her death certificate she was born in 1826, but an 1850 census shows that she could have been born in 1830. The actual date of birth was never found. Elizabeth Jennings Graham was an African-American teacher and church organist; as a young woman, she became noted as a 19th-century civil rights figure after insisting on her right to ride on an available New York City streetcar in 1854, at a time when all such companies were private and most operated segregated cars. Her case was decided in her favor in 1855, and it led to the eventual desegregation of all New York City transit systems by 1865.

After the New York Draft Riots of July 1863, where there were numerous attacks against the black community, Graham and her husband left the city, moving to join her mother and sister in Eatontown, New Jersey. After his death, she returned with her family to New York. Graham started the city’s first kindergarten for black children, operating it from her home.