Happy Friday POU!

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s death could not have been more devastating to African American communities across the country hoping to see the civil rights leader live to build on the successes of the movement. Despite King’s painfully prophetic “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech the day before his assassination in Memphis Tennessee, most people hoped to see him finish the work he’d begun. Those hopes were dashed on April, 4 1968. After King’s death, embittered and embattled minorities in cities North and South erupted in rioting. Boston—a city of de facto segregation to rival Birmingham’s—seemed poised to blow up as well in the Spring of ’68, its “race relations… already on a short fuse.” As public radio program Weekend America describes the conditions:

The tension had been escalating in the mid-60s as the city began to desegregate its public schools. The mayoral race in 1967 pitted a liberal reformer, Kevin White, against Louise Day Hicks, an opponent of desegregation. Hicks ran under the evasive slogan “You know where I stand.” White won the race by less than 12,000 votes.

On the morning after the assassination, city officials in Boston, were scrambling to prepare for an expected second straight night of violent unrest. Similar preparations were being made in cities across America, including in the nation’s capital, where armed units of the regular Army patrolled outside the White House and U.S. Capitol following President Johnson’s state-of-emergency declaration. But Boston would be nearly alone among America’s major cities in remaining quiet and calm that turbulent Friday night, thanks in large part to one of the least quiet and calm musical performers of all time. On the night of April 5, 1968, James Brown kept the peace in Boston by the sheer force of his music and his personal charisma.

Brown’s appearance that night at the Boston Garden had been scheduled for months, but it nearly didn’t happen. Following a long night of riots and fires in the predominantly black Roxbury and South End sections of the city, Boston’s young mayor, Kevin White, gave serious consideration to canceling an event that some feared would bring the same kind of violence into the city’s center. The racial component of those fears was very much on the surface of a city in which school integration and mandatory busing had played a major role in the recent mayoral election. Mayor White faced a politically impossible choice: anger black Bostonians by canceling Brown’s concert over transparently racial fears, or antagonize the law-and-order crowd by simply ignoring those fears. The idea that resolved the mayor’s dilemma came from a young, African American city councilman name Tom Atkins, who proposed going on with the concert, but finding a way to mount a free, live broadcast of the show in the hopes of keeping most Bostonians at home in front of their TV sets rather than on the streets.

Atkins and White convinced public television station WGBH to carry the concert on short notice, but convincing James Brown took some doing. Due to a non-compete agreement relating to an upcoming televised concert, Brown stood to lose roughly $60,000 if his Boston show were televised. Ever the savvy businessman, James Brown made his financial needs known to Mayor White, who made the very wise decision to meet them.

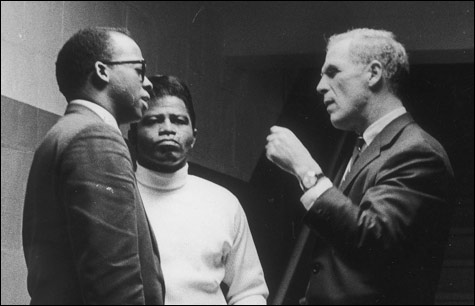

Before Brown took the microphone, the narrowly-elected Mayor White addressed the restless crowd (top), asking them to pledge that “no matter what any other community might do, here in Boston, we will honor Dr. King’s legacy in peace.” After Councilor Tom Atkin’s lengthy introduction and the mayor’s short speech, the audience seems receptive, if eager to get the show on.

The broadcast of Brown’s concert had the exact effect it was intended to, as Boston saw less crime that night than would be expected on a perfectly normal Friday in April. There was a moment, however, when it appeared that the plan might backfire. As a handful of young, male fans—most, but not all of them black—began climbing on stage mid-concert, white Boston policemen began forcefully pushing them back. Sensing the volatility of the situation, Brown urged the cops to back away from the stage, then addressed the crowd. “Wait a minute, wait a minute now WAIT!” Brown said. “Step down, now, be a gentleman….Now I asked the police to step back, because I think I can get some respect from my own people.”

His drummer John Starks remembers it this way: “It was almost at a point where something bad was going to happen. And he said [to the police] ‘Let me talk to them.’ He had that power.”

Brown successfully restored order while keeping the police away from the crowd, and continued the successful peacekeeping concert in honor of the slain Dr. King.

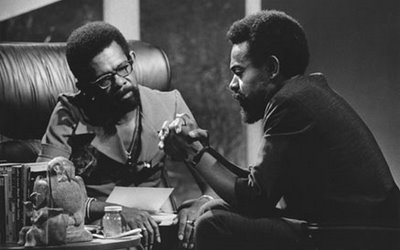

Brown’s calming effect went beyond this particular gig. See him in the footage below address an audience in Washington, D.C. two days after King’s death. “Education is the answer,” he says, and sets up his own exceptional boostrapping rise from poverty as a model to emulate (“today, I own that radio station”).

While the message from “Soul Brother Number One”—a title he accepted with humility—failed to douse the flames in cities like Washington, DC, Detroit, Chicago, and Louisville, KY, and over 100 others after King’s murder, in Boston, the audience at his concert and the people watching at home on television seemed to heed his calls for nonviolence. “Boston,” wrote Weekend America, “remained quiet.”