When University of Baltimore professor Joshua Clark Davis began research for his 2017 book “From Head Shops to Whole Foods: The Rise and Fall of Activist Entrepreneurs,” he no idea he would come across a document detailing just how insidious Hoover’s reign was over African American communities across the nation. While the extent of COINTELPRO’s involvement with Civil Rights groups has been widely known, less known was how the surveillance program tapped into some of the most benign activities of Black Americans everyday life, including a simple trip to the book store.

It’s the spring of 1968. J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI is working overtime to suppress the gathering momentum of the Black Power movement. Under the aegis of COINTELPRO, agents and informants are sniffing around for legal transgressions, or even private gossip, that might be used to take down some of the movements leaders. Hoover pens his infamous memo demanding agents focus on preventing a “black messiah” from emerging as a leader to unify and electrify the movement.

Just a few months later, in October 1968, Hoover penned another memo warning of the urgent menace of a growing Black Power movement, but this time the director focused on the unlikeliest of public enemies: black independent booksellers.

In a one-page directive, Hoover noted with alarm a recent “increase in the establishment of black extremist bookstores which represent propaganda outlets for revolutionary and hate publications and culture centers for extremism.” The director ordered each Bureau office to “locate and identify black extremist and/or African-type bookstores in its territory and open separate discreet investigations on each to determine if it is extremist in nature.” Each investigation was to “determine the identities of the owners; whether it is a front for any group or foreign interest; whether individuals affiliated with the store engage in extremist activities; the number, type, and source of books and material on sale; the store’s financial condition; its clientele; and whether it is used as a headquarters or meeting place.”

Perhaps most disturbing, Hoover wanted the Bureau to convince African American citizens (presumably with pay or through extortion) to spy on these stores by posing as sympathetic customers or activists. “Investigations should be instituted on new stores when opened and you should recognize the excellent target these stores represent for penetration by racial sources,” he ordered. Hoover, in short, expected agents to adopt the ruthless tactics of espionage and falsification they deployed against civil-rights and Black Power activists, and now use them against black-owned bookstores.

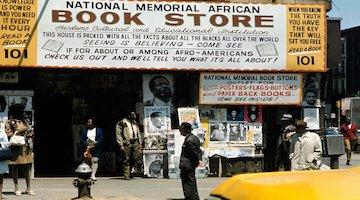

Hoover’s memo offers us a troubling glimpse of a forgotten dimension of COINTELPRO, one that has escaped notice for decades: the FBI’s war on black-bookstores. In addition to Hoover’s memo, I uncovered documents detailing Bureau surveillance of black bookstores in a least half a dozen cities across the U.S. in conducting research for my book, From Head Shops to Whole Foods: The Rise and Fall of Activist Entrepreneurs. At the height of the Black Power movement, the FBI conducted investigations of such black booksellers as Lewis Michaux and Una Mulzac in New York City, Paul Coates in Baltimore (the father of The Atlantic national correspondent Ta-Nehisi Coates), Dawud Hakim and Bill Crawford in Philadelphia, Alfred and Bernice Ligon in Los Angeles, and the owners of the Sundiata bookstore in Denver. And this list is almost certainly far from complete, because most FBI documents pertaining to currently living booksellers aren’t available to researchers through the federal Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

The FBI’s reports on black booksellers were highly invasive but often mundane. The FBI reports note phone calls from Coates’s number to his former comrades in the Black Panther Party—but also to Viking Press and the American Booksellers Association. Agents in New York reported an undercover source’s questionable claim that Lewis Michaux “was responsible for about 75 percent of the antiwhite material” distributed in Harlem, but another report conceded that he was “no longer very active in Black Nationalist activity as he is getting old.” In Philadelphia, agents traced a car’s license plate at a Republic of New Africa convention to Dawud Hakim, but not long afterwards they quoted sources stating that the RNA was “now defunct in the Philadelphia area” and that Hakim “has not shown interest in any Black Nationalist Activity.”While perhaps not surprising, it is deeply disturbing that Hoover and the FBI would carry out sustained investigations of black-owned independent bookstores across the country as part of COINTELPRO’s larger attacks on the Black Power movement. But Hoover’s order that agents track these stores’ customers represented not just an attack on black activists, but also an absolute contempt for America’s stated values of freedom of speech and expression.

(continue to page 2)