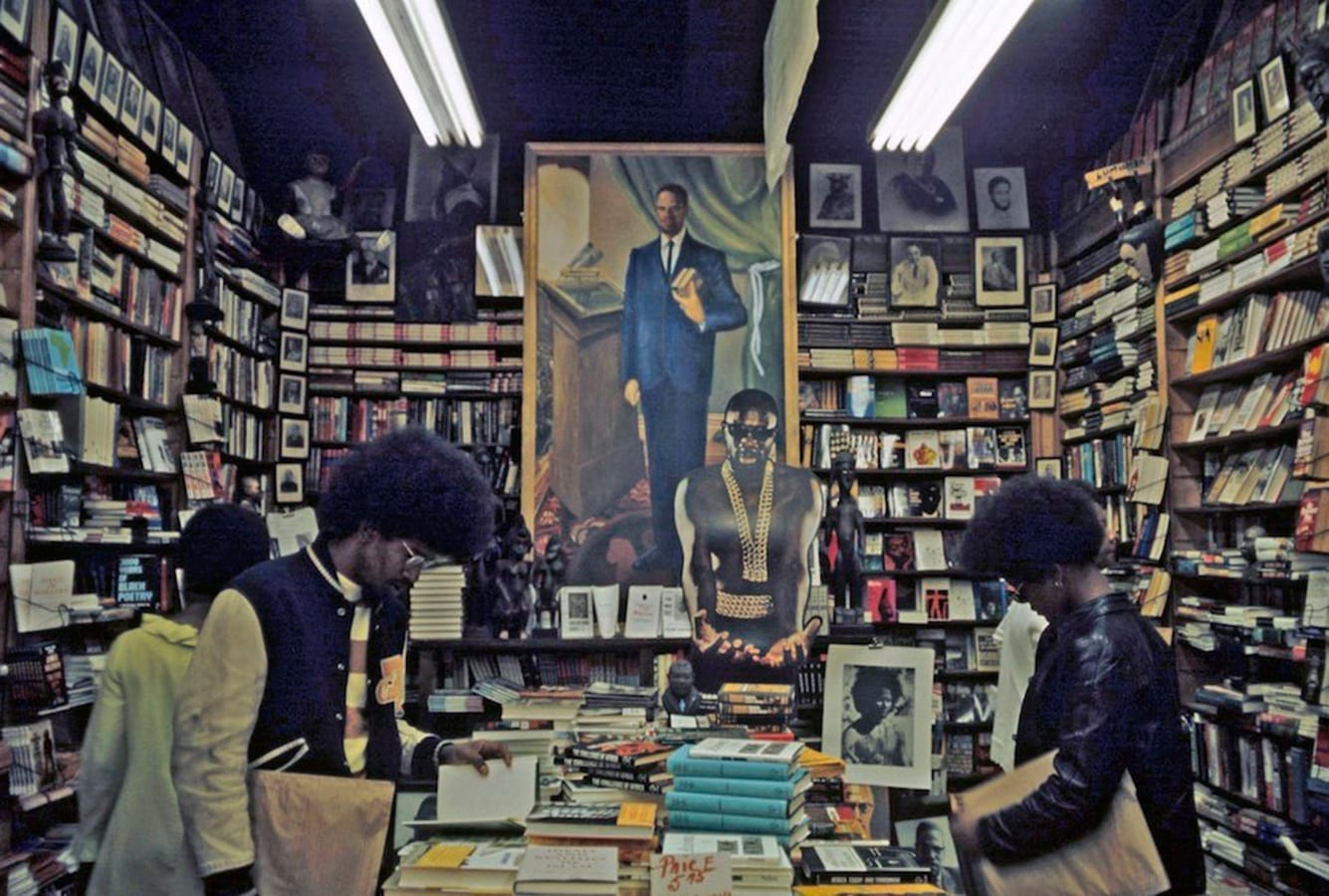

Any citizen who stepped into a black-owned bookstore, it seemed, risked being investigated by federal law enforcement.To be sure, many black bookstores did have direct connections to Black Power activists. Quite a few black booksellers themselves participated in Black Power organizations, even if those organizations didn’t operate their stores. But more often the connections between the bookstores and the movement weren’t institutional, but intellectual and informal. Customers sought out copies of such titles as The Autobiography of Malcolm X or Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice, which black booksellers gladly sold them. The rapid proliferation of black-owned bookstores in the late 1960s and early 1970s signaled African Americans’ growing appetite for black political and historical literature and reading materials on Africa. Black-owned bookstores also sold works by authors who were not formally associated with Black Power organizations, including critically acclaimed writers such as James Baldwin and Lorraine Hansberry, as well as street-literature favorites like Iceberg Slim, author of the novel Pimp.

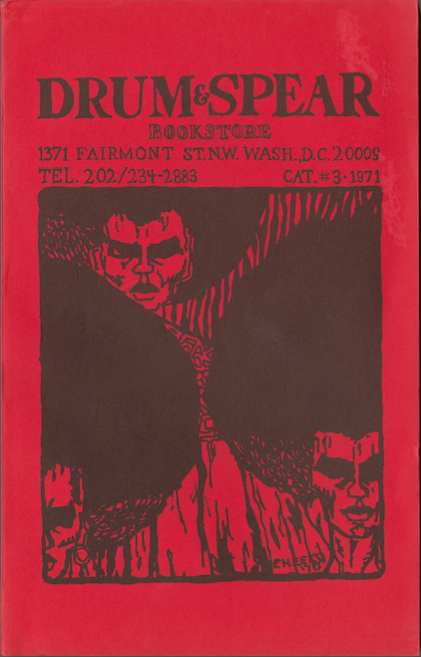

Black bookstores weren’t fronts assigned by activist organizations to distribute political propaganda. They were independent businesses serving black people’s growing appetite for books by and about black people.The Drum and Spear Bookstore in Washington, D.C., seems to have drawn more scrutiny from the Bureau’s agents than any other black bookstore. Established by veterans of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the famed direct-action civil rights organization founded in 1960, the store opened in late spring 1968 just weeks after an uprising devastated the District following the assassination of Martin Luther King. The store was an especially convenient and frequent target for federal law enforcement, both because of its ties to prominent figures in the Black Power movement, and its location in the Columbia Heights neighborhood, less than three miles away from the FBI’s headquarters.

The Bureau launched its surveillance of Drum and Spear after sources sighted Stokely Carmichael (later Kwame Ture) visiting the store in its first weeks of business. Hoover’s office soon ordered that the investigation of the store “should be intensified” beyond occasional visits by agents and expanded to cultivating customers, employees, and people who attended meetings at Drum and Spear as undercover sources. From 1968 until the store’s closing in 1974, the Bureau compiled nearly 500 pages of investigative files on Drum and Spear. Plainclothes agents who visited the store aroused employees’ suspicions when they sat in parked cars in front of the business for hours. In another incident, two men wearing suits who appeared to be federal agents visited Drum and Spear and asked to purchase the store’s entire inventory of Mao’s Little Red Book. Agents’ reports meticulously detailed the store’s contents, relating that its roughly 4,000 copies of 500 titles were divided into five sections—African Works, Works of the American Negro, Fiction, Third World, and Children’s Works—while posters and photos of H. Rap Brown, Carmichael, Huey Newton, and Che Guevara decorated its walls.

Hoover was right about one thing: black bookstores were on the rise by the end of the 1960s. As late as 1966, black-owned bookstores operated in fewer than a dozen American cities, and most of them struggled to stay in business. Within just a few years, however, the number of stores had skyrocketed. Dozens of new stores opened throughout the country in the final years of the ‘60s, roughly tripling their numbers since the start of the decade. As The New York Timesreported in 1969, “A surge of book-buying is sweeping through Black communities across the country.” What had been about a dozen black bookstores operating in the mid-1960s grew to over 50 by the early 1970s, and around 75 by the middle of the decade.

In Hoover’s eyes, black-owned bookstores represented a coordinated network of hate-spewing extremists. His clumsy invocation of the phrase “African-type bookstores” betrayed his lack of understanding of pan-Africanism, a philosophy that people of African descent around the world should unite in pursuit of shared political and social goals. To Hoover, radical anti-government organizations actively fomented black Americans’ growing fascination with Africa in the hopes of using it as a weapon against whites. But Hoover grossly mischaracterized the organic groundswell of popular interest in African history, culture, and politics spreading throughout African American communities.

As with much of COINTELPRO, Hoover took a model of counter-intelligence developed to combat the rigidly organized and centralized Communist Party of the United States of America and applied it to a much looser and decentralized array of Black Power groups emerging across the country. The CPUSA for instance, had operated a series of official bookstores carrying party literature in cities across the U.S., which the FBI had monitored since at least the 1930s. The FBI appears to have wound down its surveillance of black bookstores by the middle of the 1970s, in the wake of Hoover’s death and the formal conclusion of COINTELPRO. As the Black Power movement declined in the late 1970s, so did black bookstores, and their numbers significantly dwindled by the start of the ‘80s (before experiencing a resurgence in the early 1990s).

Looking back, it’s worth asking if the Bureau’s investigations may have undermined the viability of these black-owned businesses, creating undue stress for owners already struggling to make ends meet and scaring away customers who wanted to avoid any encounters with law-enforcement officials.Indeed, the FBI’s war against black bookstores represents a sad chapter in the history of law enforcement in the U.S., a time when federal agents dispensed with all notions of freedom of speech as they targeted black entrepreneurs and their customers for buying and selling literature they deemed politically subversive.

“It’s a waste of taxpayers’ money,” Philadelphia bookseller Dawud Hakim lamented in 1971, having learned that that he was himself a target of the Bureau’s misguided surveillance campaign. “We are trying to educate our people about their history and culture. The FBI should be spending their time instead on organized crime and dope peddlers.”

Source: The FBI’s War on Black-Owned Bookstores