Happy Friday POU!

Near the beginning of the century, public pools could be found in many urban areas across the country, but that all changed as cities moved to desegregate those swimming areas. In her book, “The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together,” Heather McGhee looks at how many cities closed their pools rather than commit to desegregation, and how this same political mindset shaped the policy making for decades to come. The following is an excerpt of McGhee’s book.

Built in 1919, the Fairground Park pool in St. Louis, Missouri, was the largest in the country and probably the world, with a sandy beach, an elaborate diving board, and a reported capacity of ten thousand swimmers. When a new city administration changed the parks policy in 1949 to allow Black swimmers, the first integrated swim ended in bloodshed. On June 21, two hundred white residents surrounded the pool with “bats, clubs, bricks and knives” to menace the first thirty or so Black swimmers. Over the course of the day, a white mob that grew to five thousand attacked every Black person in sight around the Fairground Park. After the Fairground Park Riot, as it was known, the city returned to a segregation policy using public safety as a justification, but a successful NAACP lawsuit reopened the pool to all St. Louisans the following summer. On the first day of integrated swimming, July 19, 1950, only seven white swimmers attended, joining three brave Black swimmers under the shouts of two hundred white protesters. That first integrated summer, Fairground logged just 10,000 swims—down from 313,000 the previous summer. The city closed the pool for good six years later. Racial hatred led to St. Louis draining one of the most prized public pools in the world.

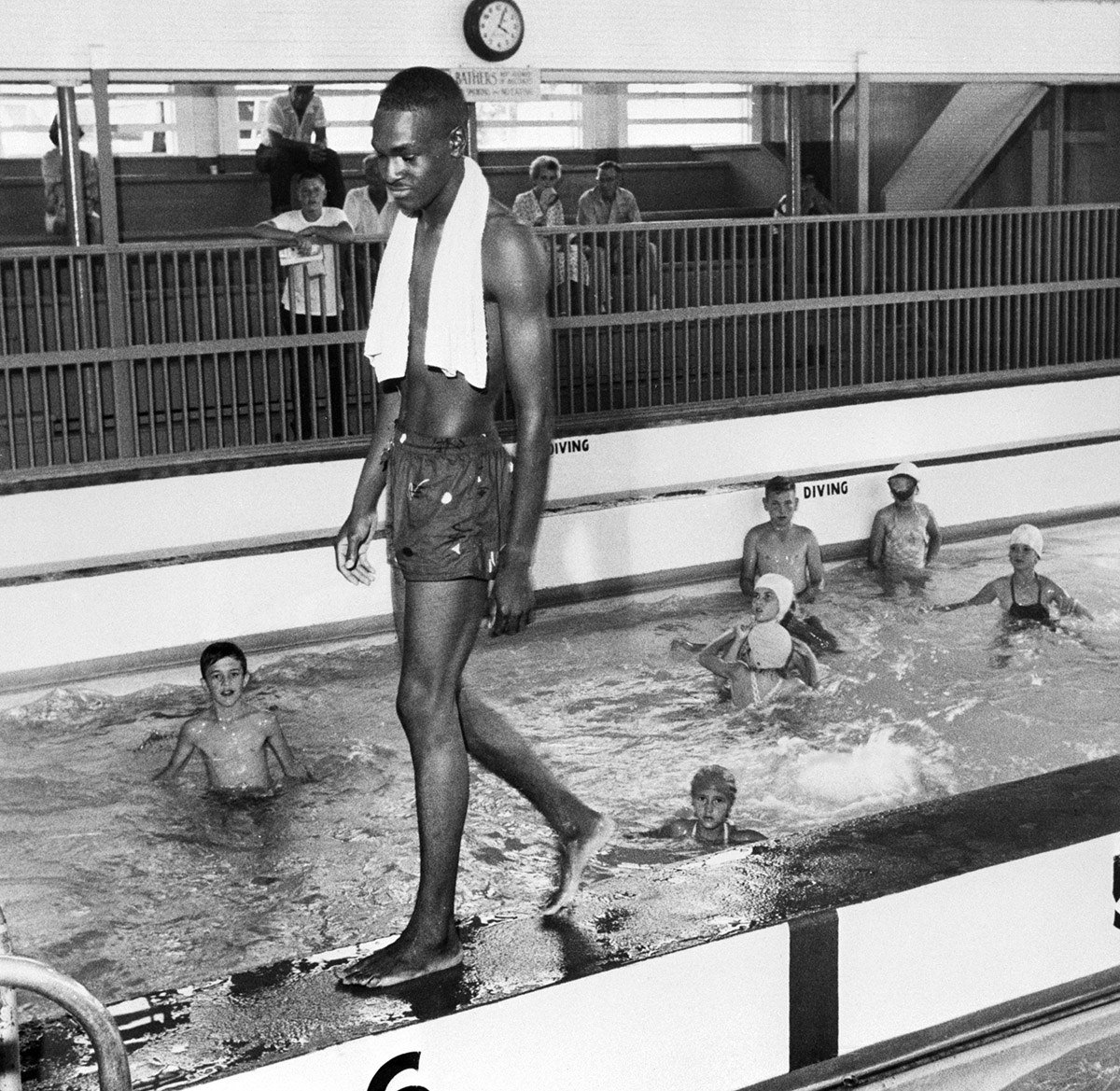

David Isom, 19, broke the color line in one of this city’s segregated public pools on June 8, 1958, which resulted in officials closing the facility.

Draining public swimming pools to avoid integration received the official blessing of the U.S. Supreme Court in 1971. The city council in Jackson, Mississippi, had responded to desegregation demands by closing four public pools and leasing the fifth to the YMCA, which operated it for whites only. Black citizens sued, but the Supreme Court, in Palmer v. Thompson, held that a city could choose not to provide a public facility rather than maintain an integrated one, because by robbing the entire public, the white leaders were spreading equal harm. “There was no evidence of state action affecting Negroes differently from white,” wrote Justice Hugo Black. The Court went on to turn a blind eye to the obvious racial animus behind the decision, taking the race neutrality at face value. “Petitioners’ contention that equal protection requirements were violated because the pool-closing decision was motivated by anti-integration considerations must also fail, since courts will not invalidate legislation based solely on asserted illicit motivation by the enacting legislative body.” The decision showed the limits of the civil rights legal tool kit and forecast the politics of public services for decades to come: If the benefits can’t be whites-only, you can’t have them at all. And if you say it’s racist? Well, prove it.

As Jeff Wiltse writes in his history of pool desegregation, Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America, “Beginning in the mid-1950s northern cities generally stopped building large resort pools and let the ones already constructed fall into disrepair.” Over the next decade, millions of white Americans who once swam in public for free began to pay rather than swim for free with Black people; desegregation in the mid-fifties coincided with a surge in backyard pools and members-only swim clubs. In Washington, D.C., for example, 125 new private swim clubs were opened in less than a decade following pool desegregation in 1953. The classless utopia faded, replaced by clubs with two-hundred-dollar membership fees and annual dues. A once-public resource became a luxury amenity, and entire communities lost out on the benefits of public life and civic engagement once understood to be the key to making American democracy real.

Today, we don’t even notice the absence of the grand resort pools in our communities; where grass grows over former sites, there are no plaques to tell the story of how racism drained the pools. But the spirit that drained these public goods lives on. The impulse to exclude now manifests in a subtler fashion, more often reflected in a pool of resources than a literal one.