Happy Friday POU!

Today we feature another head of the NAACP that risked his life to expose working conditions in 1930s Mississippi.

“Images of what I’d seen in Mississippi – the grim little river towns, rain-soaked levees, suspicious white faces, poverty-beaten Negroes…stayed fresh in my mind for a long time.”

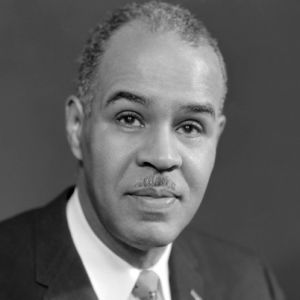

Roy Wilkins was born on August 30, 1901, in St. Louis, Missouri. After his mother died when he was just 4 years old, he and his siblings went to live with his maternal aunt and her spouse in the region of St. Paul, Minnesota. He majored in sociology and journalism at the University of Minnesota, working various jobs to support his way—including as an editor for the university newspaper and the African-American periodical The St. Paul Appeal. Wilkins graduated from the school in 1923. He then moved to Kansas City to taken an editorial job with the Kansas City Call.

Roy Wilkins, who had joined the NAACP as a collegian, decided that the best way to change the system was to fight it from within. First he used the pages of the Kansas City Call to denounce “Jim Crow” laws that everywhere segregated blacks and denied them use of the best public facilities. He called upon his black readership to register to vote and then to use the power of the ballot box to remove the most racist politicians from office. A 1930 campaign headed by Wilkins and the Call to unseat U.S. senator Henry J. Allen, for instance, was successful and became a harbinger of the political advances to come for Southern blacks.

Wilkins’s work on the campaign against Allen brought the passionate young editor to the attention of Walter White, executive secretary of the NAACP. White offered Wilkins a job as an aide in the NAACP’s New York City offices. It was not a position to be taken lightly in 1931. Wilkins’s first assignment was to go into Mississippi to investigate working conditions on a federally-funded river management project.

It was near the end of 1932, in response to reports of peonage and violence, the NAACP sent Wilkins and George Schuyler, a journalist and author, undercover to investigate conditions for the 30,000 black workers in the War Department’s Mississippi River Flood Control Project.

From December 15, 1932 to January 5, 1933, Roy Wilkins and George Schuyler investigated conditions in the construction camps of contractors building levees along the Mississippi River from Memphis south to Vicksburg, Mississippi. The pair used the home of prominent businessman Robert R. Church, Jr. in Memphis as their headquarters. Church was the half brother of NAACP founder Mary Church Terrell.

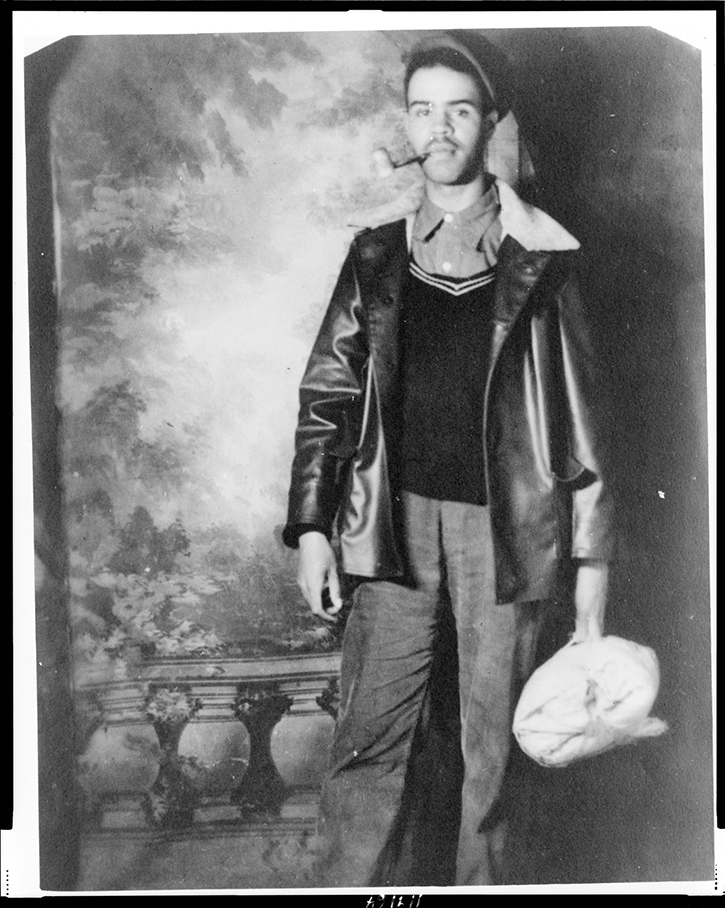

Roy Wilkins, Assistant Secretary of the NAACP, in workman’s disguise during his investigation of workers’ conditions on the Federal Flood Control Project, Memphis, Tennessee

Knowing that he would either be lynched or run out of the state if he were discovered to be with the NAACP, Wilkins donned a poor man’s clothes and went to seek work with the project. He earned ten cents an hour, lived in the floorless tents provided for the black laborers, and paid the inflated prices for basic foods at company stores. He also took notes on the conditions in preparation for his return to New York.

Schuyler was familiar with the South’s social and cultural terrain, but the mid-westerner Wilkins, had little experience “down South.” Wilkins later recalled in his autobiography Standing Fast, that he had only been to the South once in his life and was perhaps a bit naive about the risk he was taking. In the chapter “Up in Harlem, Down in the Delta,” he recalled the danger of disclosing their identity, even to black levee camp workers who might betray their trust. The entire trip would prove more daunting for Wilkins whose northern accent and upper middle class demeanor might blow his cover.

In 1932 the NAACP published Wilkins’s report, entitled Mississippi Slave Labor. The report went to Congress, prompting a federal investigation of the levee labor camps and an improvement in conditions for the workers. In September 1933, the Secretary of War announced a pay raise and shortened hours for unskilled Mississippi levee camp laborers. Wilkins quickly became an important administrator in the fast-growing NAACP and a favorite of executive secretary White as well as the rank-and-file members.