Happy Friday POU! Today we look at Freedom’s Eve.

During the days of U.S. slavery, January 1 was known as Hiring Day or Heartbreak Day — a day when business owners would collect and settle the bulk of their debts through the sale of Black people and Black labor. As a result, enslaved people would spend New Year’s Eve waiting to find out if they, or their family members, would be rented out or put up for auction on New Year’s Day.

“Of all the days in the year, the slaves dread New Year’s Day the worst of any,” Lewis Clarke, who had been born into slavery, escaped, and later became an abolitionist speaker, said in 1842. “For folks come for their debts then; and if anybody is going to sell a slave, that’s the time they do it; and if anybody’s going to give away a slave, that’s the time they do it; and the slave never knows where he’ll be sent to. Oh, New Year’s a heart-breaking time in Kentucky!”

Then, on December 31, 1862, the significance of the holiday dramatically changed for the United States’ Black population. One of the most notable New Year’s Eves in U.S. history, also referred to as Freedom’s Eve, marked the brink of the first major step in the path to freedom for Black Americans. On that New Year’s Day, January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. While this pivotal document was intended to preserve the Union rather than act as means of liberation, it effectively freed enslaved Black people in the Confederate states that had seceded from the Union.

Slavery wasn’t fully abolished until the end of the Civil War in April 1865 — with the last enslaved people learning of their freedom on June 19 of that year (Juneteenth) — and it wasn’t officially outlawed until the December 1865 ratification of the 13th Amendment. Still, the course of Black American history changed forever on that New Year’s Day.

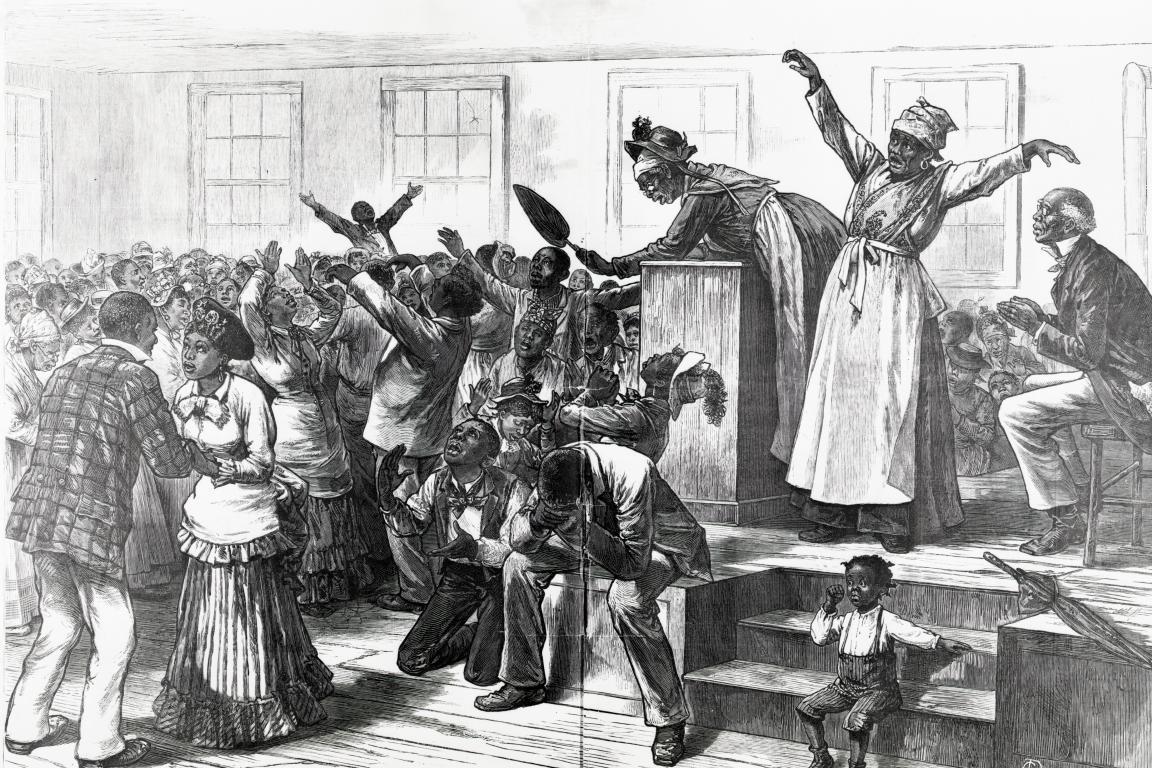

In anticipation of that historical moment, Black people gathered in homes and churches on Freedom’s Eve, waiting for confirmation that the Emancipation Proclamation had officially been issued. They were watching out for notification by newspaper, telegraph, or word of mouth on what is now referred to as the first Watch Night.

American abolitionist Frederick Douglass is said to have described the moment he heard news of the Proclamation like so: “The scene was wild and grand. Joy and gladness exhausted all forms of expression, from shouts of praise to joys and tears.” In the years since, Watch Night services honoring that Freedom’s Eve have been held at Black churches nationwide.