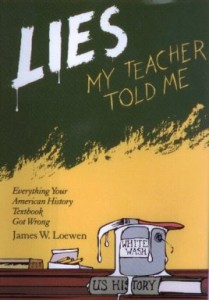

What your teacher told you: John Brown was an insane antiracist who hated himself and others white people. He was delusional.

Abraham Lincoln free the slaves, so therefore he can’t be racist.

The Truth: 1. “Just as textbooks treat slavery without racism, they treat abolitionism without idealism. Consider the most radical white abolitionist of them all, John Brown.”

2. “The treatment of Brown, like the treatment of slavery and Reconstruction, has changed in American history textbooks. From 1890 to about 1970, John Brown was insane. Before 1890 he was perfectly sane, and after 1970 he regained his sanity. Since Brown himself did not change after his death, his sanity provides an inadvertent index of the level of white racism in our society.”

3. “We must recognize that the insanity with which historians have charged John Brown was never psychological. It was ideological. Brown’s actions made no sense to textbook writers between 1890 and about 1970. To make no sense is to be crazy.”

4. “Brown’s charisma in the North [sic] was not spent but only increased due to what many came to view as his martyrdom. As the war came, as thousands of Americans found themselves making the same commitment to face death that John Brown had made, the force of his example took on new relevance.”

5. “Quite possibly textbooks should not portray this murderer as a hero, although other murderers, from Christopher Columbus to Nat Turner, get the heroic treatment. However, the flat prose that textbooks use for Brown is not really neutral. Textbook authors’ withdrawal of sympathy from Brown is perceptible; their tone in presenting him is different from the tone they employ for almost everyone else.”

6. “Our textbooks also handicap Brown by not letting him speak for himself. Even his jailer let Brown put pen to paper! American History includes three important sentences; American Adventures gives us almost two. The American Pageant reprints three sentences from a letter Brown wrote his brother. The other nine books do not provide even a phrase. Brown’s words, which moved a nation, therefore do not move students today.”

7. “Conceivably, textbook authors ignore John Brown’s ideas because in their eyes his violent acts make him ineligible for sympathetic consideration.”

8. ““Lincoln, like most whites of his century, referred to blacks as “niggers.” In the Lincoln-Douglas debates, he sometimes descended into explicit white supremacy…. Lincoln’s attitudes about race were more complicated than Douglas’s however. The day after Douglas declared for white supremacy in Chicago, saying the issues were “distinctly drawn,” Lincoln replied and indeed drew the issue distinctly: “I should like to know if taking this old Declaration of Independence, which declares that all men are equal upon principle, and making exceptions to it-where will it stop? If one man says it does not mean a Negro, why does not another say it does not mean some other man? If that Declaration is not…true, let us tear it out! [Cries of “no, no!”] Let us stick to it them, let us stand firmly by it then.” No textbook quotes this passage, and every book but one leaves out Lincoln’s thundering summation of what his debates with Douglas were really about: “That is the issue that will continue in this country when these poor tongues of Judge Douglas and myself shall be silent. It is the eternal struggle between these two principles-right and wrong-throughout the world.””

9. “As president, Lincoln understood the importance of symbolic leadership in improving race relations.”

10. “Abraham Lincoln was one of the great masters of the English language. Perhaps more than any other president he invoked and manipulated powerful symbols in his speeches to move public opinion, often on the subject of race relations and slavery. Textbooks in keeping with their habit of telling everything in the authorial monotone, dribble out Lincoln’s words three and four at a time.”

11. “Textbooks need not explain Lincoln’s words at Gettysburg as I have done. The Gettysburg Address is rich enough to survive various analyses. But of the four books that do reprint the speech, three merely put it in a box by itself in a corner of the page. Only Life and Liberty asks intelligent questions about it. As a result, I have yet to meet a high school graduate who has devoted any time to thinking about the Gettysburg Address.”

12. The antiracist repercussions of the Civil War were particularly apparent in the border states. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation applied only to the Confederacy. It left slavery untouched in Unionist Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri. But the war did not. The status of planters became ambiguous: owning black people was no longer what a young white man aspired to do or what a young white woman aspired to accomplish by marriage.”

13. “Songs such as “Nigger Doodle Dandy” reflect the racist tone of the Democrats’ presidential campaign in 1864. How did republicans counter? In part, they sought white votes by being antiracist. The Republican campaign, boosted by military victories in the fall of 1864, proved effective. The Democrats’ overt appeals to racism failed, and antiracist Republicans triumphed almost everywhere.”

14. “Antiracism is one of America’s great gifts to the world. Its relevance extends far beyond race relations. Antiracism led to “a new birth of freedom” after the Civil War, and not only for African Americans. Twice, once in each century, the movement for black rights triggered the movement for women’s rights. Twice it reinvigorated our democratic spirit, which had been atrophying. Throughout the world, from South Africa to Northern Ireland, movements of oppressed people continue to use tactics and words borrowed from our abolitionist and civil rights movements. The clandestine early meetings of anticommunists in East Germany were marked by singing “We Shall Overcome.” [etc.]…Yet we in America, whose antiracist idealists are admired around the globe, seem to have lost these men and women as heroes. Our textbooks need to present them in such a way that we might again value our own idealism.”