Good Morning POU! There is no denying the incredible impact of John Thompson and the Georgetown Hoyas on college hoops. John Thompson embraced “those” kids from the inner cities and changed the game.

The relationship between Georgetown basketball and Black America is symbiotic. Georgetown basketball would be nowhere near what it is today if not for shaping popular culture and reaching into the Black community. When the Hoyas started winning with these types of kids, Black America noticed.

“In its dominant years, I mean, from East Coast to West Coast, Georgetown was well known. It was almost known as an HBCU,” forward Jerome Williams (COL ’96) said. “It was one of the original HBCUs that most people recognize because of basketball.”

“We were once Black America’s team! That wasn’t something we were aware of while we were playing,” guard Gene Smith (COL ’84) said. “We were just organized, moved to a singular beat and that was Big John, we were serious, we played a certain way, and we were part of a movement. You look at the world from a cultural standpoint, and we fit right in.”

“I can’t really name any other school outside of that, that had that connection to the Black community as Georgetown throughout history, from what I can remember,” guard Jabril Trawick (COL ’15) said. “If you know, you know. You can’t overwrite that history and the connection.”

“I came back after my first year to Jersey, and people were saying they thought that [Georgetown] was mostly a Black school because the basketball team was mostly Black players,” guard Jagan Mosely (MSB ’20) said.

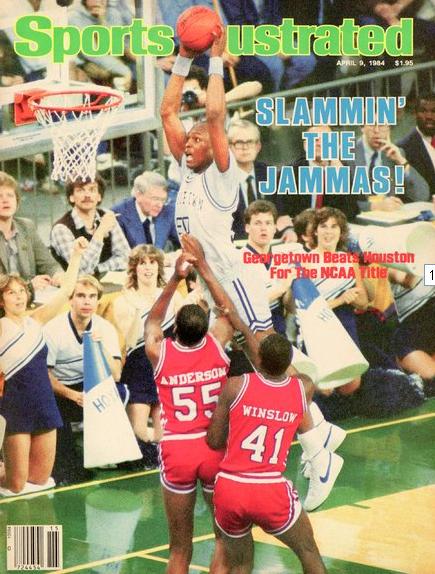

Though it was uncomfortable for white America to digest an all-Black team at an elite, predominantly white institution, it was set up to be the anti-establishment school for Black basketball fans to unite around. The Hoyas may have only captured one championship, but the cultural impact they left on the intersection of sports and entertainment is still felt today. Before the Runnin’ Rebels of UNLV, before the Fab Five of Michigan, there was Hoya Paranoia.

“We were disruptive in the ‘80s,” Smith recalled. “Hoya Paranoia was disruptive. We had grown ass sports announcers calling us thugs.”

Georgetown’s basketball teams remained steadfast and were never deferential to the whims of white America, in recruiting or otherwise. They didn’t give in easily to the wishes of the media, as they did not allow players in their first semester of school to speak at press conferences. They played a physical brand of basketball that matched the play style of the other Big East schools. They pushed, clawed, fought, spit, and did whatever it took to win a basketball game.

“He pimped the media,” Smith said about Coach John Thompson, Jr. “He created that environment and that worked for us. But also for Black America, it was like, ‘Okay, we’re not taking any shit. We’re not apologizing.’”

Their impact on popular culture manifested itself in two important forms: gear and rap music. Coach Thompson immediately recognized the impact that the Georgetown brand could have by plastering the logo everywhere.

When Nike came calling, Coach Thompson was ready. He immediately took a position on their board of directors and was paid a salary in the millions. He demanded that Georgetown get an exclusive version of the Nike Terminator basketball shoe, engineered to fit the word “HOYAS” on the back. Wearing those sneakers allowed an individual to express Georgetown’s popular, aggressive brand, and it let the ordinary fan be a part of the supposedly inaccessible Hoya Paranoia. The shoes alone had such a large impact that even opposing players were waiting in line to purchase them.

“I couldn’t wear a Georgetown jacket but I had a pair of those shoes,” Villanova center Ed Pinckney said in the 2014 documentary Requiem for the Big East. “Did I go to Villanova? Yes. But I was also gonna be part of the crowd, and I was gonna represent. Wearing Georgetown gear said something about your consciousness and what you were about. I’m tough. You could wear the gear and not have to proclaim that.”

The impact of the shoes extended beyond just the players in the Big East. It was a way that Georgetown connected to the streets of D.C. The most notable example is the New Balance sneaker, promoted by drug kingpin and rabid Hoyas fan Rayful Edmond III. At the height of his cocaine empire in D.C., Edmond sat courtside at nearly every Hoyas game, building relationships with forward John Turner and center Alonzo Mourning (COL ‘92).

Though he was eventually put in his place by Coach Thompson and was no longer allowed to directly interact with players, he repped the New Balance 990, a revolutionary shoe that was a symbol of the D.C.-Baltimore area. It was no coincidence that the 990s were released in 1982, the year Georgetown first made the championship game. It was no coincidence that the 990s were grey.

Beyond just the sneakers, other forms of Georgetown gear were becoming popular as well. After Ewing wore a gray t-shirt underneath his jersey for one game because he had a cold, even that became a trend, as Mourning, Mutombo, and Iverson followed in his footsteps. During the Iverson years, Georgetown’s uniforms added the West African royalty pattern known as Kente on the sides, cementing Georgetown’s connection with not only African-Americans but also Africans.

“That definitely put a different spin on Georgetown, and we were also the first school to rock Jordan 11s,” Williams said. “So that same year with the Kente cloth as well as the Jordans were just groundbreaking and I was so happy to be a part of that. People are still rocking them to this day. As you know, Jordan 11s are some of the most widely sought after Jordans on the planet.”

One of the most influential pieces of Georgetown gear was the iconic blue and gray satin Starter jacket, and this piece of clothing tied the closest to rap music. By the 1980s, rap was emerging as an incredibly popular part of hip-hop culture and an expression of Black anger towards an oppressive system. In this setting, Georgetown fit perfectly.

Chuck D, the leader of the rap group Public Enemy, once envisioned forming the “Georgetown Gangsters,” who would rep the Starter jackets in their videos. Darryl McDaniels, the founder of Run-DMC, echoed Pinckney’s sentiments, proclaiming that wearing the jacket “meant that you had attitude, that you was bad.”

“When you have players like Snoop Dogg and Ice Cube wearing Georgetown gear in movies and videos—and that’s on the West Coast and this is an East Coast school—that bolstered Georgetown’s presence,” Williams said. “A lot of young African Americans viewed it as a Black school because it had a Black coach with all Black players at a time when that was very rare.”

Georgetown’s impact in rap music is evident even to this day. In 2012, Northwest D.C. native Wale released the song “Georgetown Press” in his eighth mixtape, Folarin. In the song, Wale refers to “the trap” many times. It serves a double meaning, with trap referring to the system of drugs and violence that incarcerates Black people with no resources to escape, but also as the system of pressing defense Georgetown played, suffocating opponents in the process.

The song also reveals the program’s nuanced history. Wale references Edmond several times in the track, acknowledging his impact as a Hoyas fan on D.C. youth while also exposing that the cocaine business driving Edmond’s wealth and notoriety ultimately oppressed Black people in D.C. too.

Wale took the Georgetown connection a step further. Here are some selected verses from the song:

But ‘Le like Kevin Braswell with the rock/600 plus assists, plus this I mustn’t miss

When we can’t hit the league we let the streets mislead and dictate/And there is no I in team, but can you read the eye on Vic’s Page

He recalls Kevin Braswell, the tenth-leading scorer and leader in career assists for the Hoyas, who hasn’t been referenced by the program for many years. He also invokes Victor Page, the fiery guard who followed in Iverson’s footsteps and left school early for the NBA. Both Braswell and Page are players that more casual fans may not have previously heard of, but Wale and many other rappers bridge the gap between Georgetown basketball’s past and the kids of today.

Oftentimes the players were hardly aware of their own impact. “I didn’t find out what the program meant on that level until I moved to New York. And my New York brethren was like, ‘y’all were everything,’” Smith said. “‘You guys represented everything. You guys were an HBCU for us.’ I just think as a university that’s so dope.”

What they were aware of was that the impact Georgetown had on their lives was just as great as the impact Georgetown had on basketball and hip-hop culture.

“Going to Georgetown changed my world, man, not just basketball,” Smith asserts. “I wasn’t recruited, though I had one other scholarship offer. And the fact that I was able to make the career I made? That can only happen at Georgetown.”

“I didn’t choose Georgetown to make the NBA,” Williams said. “I chose Georgetown because I knew if I graduated, I would be able to live and take care of my family, and that’s what I’ve been able to do.”

As Mosely put it, “Going to Georgetown was more so like a 40-year plan for me rather than a 4-year plan.”

As one of the most prestigious schools in the country, Georgetown is designed to be a 40-year plan. Coach Thompson made sure that design extended to his players too, emphasizing the importance of education. Michael Graham was ineligible for the 1984-85 team not because he failed to meet university academic standards, but rather because he failed to meet Coach Thompson’s standards.

“Looking at the bigger picture, I was like, ‘If I wanted to go into the corporate world or whatever that may be after school, having a Georgetown stamp and the label, it goes a far way,’” Trawick said. “Being at Georgetown, it was great to just have access to those different resources, you know, meeting those different people, learning different things just by being there and just to get my experience.”

The Georgetown stamp is a mark that every student has to earn, and each player has to put in the work in the classroom as well. The program creates citizens with informed opinions on a wide variety of issues, who also happen to play basketball at a high level.

“Clearly, there’s been people put in positions for years and years, and we see that things really haven’t changed,” Trawick said. “People are still screaming the same thing, racially, so at the end of the day, we’re heading toward a time where people are looking for new solutions or new ways and having new understandings, new perspectives on how to make a difference.”

“One of the things I’m talking to my team about is that we have to vote,” said Ewing, who has continued to educate his players the same way Coach Thompson did with him. “Not only for the president in office that has the same view that we do, but also in our local government. We have to put people in power that’s going to make changes that will benefit the whole, not just a few.”