Good Morning POU!

One thing I’ve learned from reading this book, Miss Anne in Harlem…is that Zora Neal Hurston, chief among others, took full advantage of these arrogant patronizing Miss Annes and felt no guilt about it. I had to wipe tears I was so proud.

Today we look at the founder of one of the most elite liberal women’s colleges in the country and one of the “Seven Sister” schools, Barnard College – Annie Nathan Meyer.

She was born in New York City, the daughter of Annie August and Robert Weeks Nathan. The Nathans were one of America’s colonial-era Sephardic families. Meyer was self-educated and claimed to have read all of Dickens‘ work by the age of seven. Meyer tutored herself in order to enroll in the newly established Columbia College Collegiate Course for Women in 1885. The course did not recognize participants as fully enrolled students, because, at the time, Columbia University did not officially enroll women. She did not attend because she married Alfred Meyer, a prominent physician and a second cousin on February 15, 1887.

Within weeks of her wedding, Meyer began organizing a committee to fund a women’s college at Columbia in an effort to provide young women the opportunity for an education that she herself had not enjoyed. She overcame the opposition of the Columbia University trustees by naming the college after Frederick Barnard, Columbia’s recently deceased president and a strong advocate for coeducation. The college Meyer founded, Barnard College, is one of the Seven Sisters and ranks today as one of America’s most elite colleges.

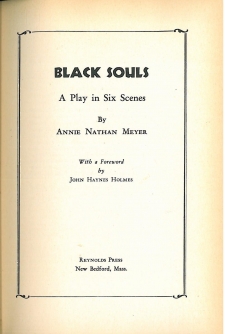

By 1924, Meyer was already the author of eight successful plays, numerous novels, many essays, and hundreds of editorials. Not entirely satisfied with any of them, she began drafting what she considered her most daring and important work: a short play called Black Souls. She wrote during a time when many successful “Negro plays” were by white authors. But she disdained the work of other white writers as not “authentic” and was determined to make her mark by doing something “bigger.”

She stopped pouring her energies into her “own” community and her “own” people. For Jewish women like Meyer, there may have been particular temptations associated with activist work in Harlem. Jewish activists might become “white” people in Harlem, when many had never before experienced themselves as “whites” in the larger American culture. For them, being white in Harlem but Jewish (and hence not fully white) elsewhere provided special insights into the relative nature of all social identities, as well as a status otherwise unobtainable. “God! I’d like to be recognized,” she wrote in 1924, hard at work on her play Black Souls.

Black Souls told the story of a white southern woman’s desire for a black man. It did not pretend that she had been seduced. It did not suggest that she had been deceived. It did not moralize against her desire. The appeal of her intended was treated as a given. This, in Meyer’s day, was unheard of. As a white woman, Meyer “felt utterly unworthy” to accomplish such a “great theme.” “Never approached a theme with such humility,” she noted. So she took her drafts to her friends Mary White Ovington and James Weldon Johnson.

Miss Ovington heard me read it before I went—thinks climax builds superbly but thinks [first?] scenes drag. . . . I must reread it carefully trying to have less talk & less propaganda. . . . A few sentences are academic rather than from the heart. . . . Miss Ovington tho’t play immensely improved since she had heard it a month before.

Last night I read it to James Weldon Johnson colored poet, orator & organizer & his charming wife. They were much moved. . . . All thot it true—one breathed a sigh when I finished & cried out “Dynamite!”

She asked Johnson to edit and authenticate the work, but she also felt she needed the input of a black woman writer. The perfect opportunity presented itself at the 1925 Opportunity awards, where she met Zora Neale Hurston and found her enormously engaging. Within a week she had sent Hurston money, recommended her to a friend who was a Vanity Fair editor, and helped arrange for Hurston to work with Fannie Hurst. She used her pull to persuade Barnard to accept Hurston on a scholarship, though no black student had ever been admitted before. Your interest “keys me up wonderfully,” Hurston told her.

They approached each other as fellow writers, sharing story ideas, outlines, and drafts. But Meyer also became Hurston’s most important “Negrotarian.” “ I must not let you be disappointed in me,” Hurston wrote to her on May 12. Hurston’s early letters to Meyer adopt a mock-servile pose: “Your grateful and obedient servant”; “Your little pickaninny”; “Yours most humbly & gratefully”; and so on, all designed to give Meyer honorary status as a Harlem insider with whom one could joke about race.

Meyer first shared Black Souls with Hurston as early as the fall of 1925 or winter of 1926. Hurston wrote back that Black Souls was “immensely moving . . . accurate . . . [and] brave, very brave without bathos.” At first Hurston hoped that she would act in the play, in the role of Phyllis. “I want to be the principal’s wife so badly.” She became the play’s advocate, talking to “every one of the literary people” and “scouting around” for singers, “trying to pick them up off of Lenox Ave.” Meyer soon became convinced that Hurston should rewrite Black Souls as a novel.

On January 21, 1927, as Hurston was heading south on her first folklore-collecting mission as Charlotte Mason’s “agent,” Meyer offered terms: “[If] the book is published, I shall make full acknowledgement. . . . Also I shall give you one half (½) of all royalty received by me. . . . I shall give them to you also if a Movie is made from the novel, but not if a play is produced, because I have already done the play. . . . I do hope you will enjoy making it into a real novel.”

By March, in spite of crisscrossing Florida, collecting folklore, starting a novel, and getting herself engaged, Hurston was able to reassure Meyer that she had already completed the first thirty pages of a rewrite. “I hope you will like what I have done on the story,” she wrote. By fall she had finished the first draft. But now she felt that the crucial interracial love story “would strike a terribly false note” in the South, especially. I could “go over it with you page by page,” she offered. Meyer was committed to that scene, and rather than drop it from the play, she let their collaboration fade.

As it turned out, the scene that Hurston thought should be removed was in fact too controversial. Despite the approval of many of Meyer’s friends and collaborators, no producer would touch the play. Annie Nathan Meyer had the persistence of a tugboat. The resistance to her play convinced her of its merit, and she labored on it doggedly for the next eight years. Finally, in 1932, the Provincetown Playhouse on MacDougal Street in Greenwich Village decided to stage Black Souls. Featuring some of Harlem’s most celebrated actors, including Rose McClendon in a starring role, and involving the design and directing talents of many of the best artists in Greenwich Village, Black Souls opened to great fanfare, mixed reviews, and one of the most heated controversies in the history of modern American theater. All of Annie Nathan Meyer’s friends had advised her that she would never find “any manager bold enough to produce” the love scene between white Luella and black David. But for Meyer, that love scene was the heart and soul of the play.

When the Provincetown Playhouse finally staged Black Souls , the country was also in a deep economic depression that hit the arts and Harlem especially hard. Since “Negro plays” were now considered too risky and producers wanted private backers to finance productions, (as Charlotte Mason had done with Hurston’s The Great Day two months earlier), Meyer agreed to finance Black Souls herself. She had been born with a surfeit of self-confidence and a prodigious capacity for work. She was capable, opinionated, and stubborn.

Opening night looked promising. The theater was standing room only. Ticket sales were a healthy $286 for the evening. But white critics savaged the play’s opening night. By the second day, the number of tickets sold dropped from 220 to only 24. By the end of the fourth night, the play had lost $452.93. Subsequent performances fared no better. On Tuesday, April 5, the Provincetown Playhouse sponsored a special “Barnard Night” with speeches on Black Souls by Meyer, Hurston, and Fannie Hurst. Unfortunately, with 154 of the 220 seats for the special performance left unsold, the show netted only $21.50. Black Souls limped into the next weekend, netting a nearly $4,000 loss before closing on April 10.

In May 1933, advertised prominently as the author of Black Souls , Meyer appeared in Opportunity as a featured reporter on black life, providing a firsthand account, with analysis, of “Negro student” attitudes toward American communism. She used her platform similarly throughout the 1930s and 1940s, giving addresses on a range of race-related issues at churches, black schools and colleges, and institutions from the Urban League to the historian Carter Woodson’s highly regarded black research organization, the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. Excepting her good friend Mary White Ovington, no white woman (except Hurst)—at least none whom Meyer knew—could boast as long or as distinguished a New York career as an expert on race. When possible, she combined her standing as a Nathan with her status as a racial expert.

In her twenties, Zora Neale Hurston found a group of patrons who would support her for the rest of her life. Among this group, which Hurston called the “Negrotarians”, was Barnard college founder Annie Nathan Meyer. Meyer met Hurston at an awards dinner, and by the night’s end she had offered the young writer a place at Barnard. Hurston dedicated her book, Mules and Men, to Meyer, “who hauled the mud to make me but loves me just the same.” In this letter, written in the first year of their friendship, Hurston updates Meyer on her work, mentioning some “ultra-free verse” poems that she never published.

May 12, 1925

My Dear Mrs. Meyer,

I have been waiting to hear from my request for a transcript of my record. It must be attended to by now.

I am tremendously encouraged now. My typewriter is clicking away till all hours of the night. I am striving desperately for a toe-hold on the world. You see, your interest keys me up wonderfully—I must not let you be disappointed in me.

No, no the little praise I have received does not affect me unless it be to make me work furiously. Instead of a pillow to rest upon, it is a goad to prod me. I know that I can only get into the sunlight by work and only remain there by more work. But you do help me immensely. It is pleasant to have someone for whom one thinks. It is mighty cold comfort to do things if nobody cares whether you succeed or not. It is terribly delightful to me to have someone fearing with me and hoping for me, let alone working to make some of my dreams come true.

ls Mr. Meyer improving? I hope so, truly. I am sending a bit of ultra-free verse for him to take his medicine by (weak ending). All of the Editors of Verse Magazine are panting to know who the author of this masterpiece is—but you are my friend and must not expose me. Editors are violent men.

Yes, I look forward eagerly to that brief chat with you before you go away. I say brief because you have so little time and I do not wish to tax your kindness too much. Hoping to have another letter from you, I am, Mrs. Meyer

Your grateful and obedient servant,

Zora Neale Hurston