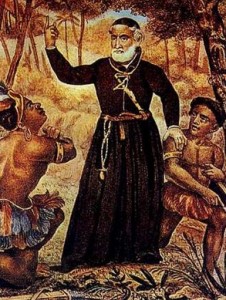

Father António Vieira (February 6, 1608, Lisbon, Portugal – July 18, 1697, Bahia,Portuguese Colony of Brazil) was a Portuguese Jesuit philosopher and writer, the “prince” of Catholic pulpit-orators of his time.

Vieira was born in Lisbon to Cristóvão Vieira Ravasco, the son of a mulatto woman, and Maria de Azevedo. In 1614 he accompanyied his parents to the colony of Brazil, where his father had been posted as a registrar. He received his education at theJesuit college at Bahia. He entered the Jesuit novitiate in 1625, under Father Fernão Cardim, and two years later pronounced his first vows. At the age of eighteen he was teaching rhetoric, and a little later dogmatic theology, at the college of Olinda, besides writing the “annual letters” of the province.

In 1635 he entered the priesthood. He soon began to distinguish himself as an orator, and the three patriotic sermons he delivered at Bahia (1638–40) are remarkable for their imaginative power and dignity of language. The sermon for the success of the arms of Portugal against Holland was considered by the Abbé Raynal to be “perhaps the most extraordinary discourse ever heard from a Christian pulpit.

When the revolution of 1640 placed John IV on the throne of Portugal, Brazil gave him its allegiance, and Vieira was chosen to accompany the viceroy’s son to Lisbon to congratulate the new king. His talents and aptitude for affairs impressed John IV so favorably that he appointed him tutor to the Infante Dom Pedro, royal preacher, and a member of the Royal Council.

Vieira did efficient work in the War and Navy Departments, revived commerce, urged the foundation of a national bank and the organization of the Brazilian Trade Company.

Vieira used the pulpit to propound measures for improving the general and particularly the economic condition of Portugal. His pen was as busy as his voice, and in four notable pamphlets he advocated the creation of companies of commerce, denounced as unchristian a society which discriminated against New Christians (Muslim and Jewish converts), called for the reform of the procedure of the Inquisition and the admission of Jewish and foreign traders, with guarantees for their security from religious persecution. Moreover, he did not spare his own estate, for in his Sexagesima sermon he boldly attacked the current style of preaching, its subtleties, affectation, obscurity and abuse of metaphor, and declared the ideal of a sermon to be one which sent men away ” not contented with the preacher, but discontented with themselves.”

In 1647 Vieira began his career as a diplomat, in the course of which he visited England, France, the Netherlands and Italy. In his Papel Forte he urged the cession of Pernambuco to the Dutch as the price of peace, while his mission to Rome in 1650 was undertaken in the hope of arranging a marriage between the heir to the throne of Portugal and the only daughter of King Philip IV of Spain. His success, freedom of speech and reforming zeal had made him enemies on all sides, and only the intervention of the king prevented his expulsion from the Society of Jesus, so that prudence counselled his return to Brazil.

In his youth he had vowed to consecrate his life to the conversion of the African slaves and native Indians of his adopted country, and arriving in Maranhão early in 1653 he recommenced his apostolic labors, which had been interrupted during his stay of fourteen years in the Old World. Starting from Pará, he penetrated to the banks of the Tocantins, making numerous converts to Christianity and European civilization among the most violent tribes; but after two years of unceasing labor, during which every difficulty was placed in his way by the colonial authorities, he saw that the Indians must be withdrawn from the jurisdiction of the governors, to prevent their exploitation, and placed under the control of the members of a single religious society.

Accordingly, in June 1654 he set sail for Lisbon to plead the cause of the Indians, and in April 1655 he obtained from the king a series of decrees which placed the missions under the Society of Jesus, with himself as their superior, and prohibited the enslavement of the natives, except in certain specified cases. Returning with this charter of freedom, he organized the missions over a territory having a coast-line of 400 leagues, and a population of 200,000 souls, and in the next six years (1655–61) the indefatigable missionary set the crown on his work. After a time, however, the colonists, attributing the shortage of slaves and the consequent diminution in their profits to the Jesuits, began actively to oppose Vieira, and they were joined by members of the secular clergy and the other Orders who were jealous of the monopoly enjoyed by the Company in the government of the Indians.

Vieira was accused of want of patriotism and usurpation of jurisdiction, and in 1661, after a popular revolt, the authorities sent him with thirty-one other Jesuit missionaries back to Portugal. He found his friend King John IV dead and the court a prey to faction, but, dauntless as ever in the pursuit of his ambition, he resorted to his favorite arm of preaching, and on Epiphany Day, 1662, in the royal chapel, he replied to his persecutors in a famous rhetorical effort, and called for the execution of the royal decrees in favor of the Indians.

Circumstances were against him, however, and the count of Castelmelhor, fearing his influence at court, had him exiled first to Porto and then to Coimbra; but in both these places he continued his work of preaching, and the reform of the Inquisition also occupied his attention. To silence him his enemies then denounced him to that tribunal, and he was cited to appear before the Holy Office at Coimbra to answer points smacking of heresy in his sermons, conversations and writings. He had believed in the prophecies of a 16th-century shoemaker poet, Bandarra, dealing with the coming of a ruler who would inaugurate an epoch of unparalleled prosperity for the church and for Portugal, these new prosperous times were to be called the Quinto Império or “Fifth Empire” (also called “Sebastianism”). In Vieira’s famous opus, Clavis Prophetarum he had endeavoured to prove the truth of his dreams from passages of Scripture. As he refused to submit, the Inquisitors kept him in prison from October 1665 to December 1667, and finally imposed a sentence which prohibited him from teaching, writing or preaching.

It was a heavy blow for the Society, and though Vieira recovered his freedom and much of his prestige shortly afterwards on the accession of King Pedro II, it was determined that he should go to Rome to procure the revision of the sentence, which still hung over him though the penalties had been removed. During a six years’ residence in the Eternal City, Vieira won his greatest triumphs. Pope Clement X invited him to preach before the College of Cardinals, and he became confessor to Queen Christina of Sweden and a member of her literary academy.

At the request of the pope he drew up a report of two hundred pages on the Inquisition in Portugal, with the result that after a judicial inquiry Pope Innocent XI suspended it in Portugal for seven years (1674–81). Ultimately Vieira returned to Portugal with a papal bull exempting him from the jurisdiction of the grand inquisitor, and in January 1681 he embarked for Brazil. He resided in Bahia and occupied himself in revising his sermons for publication, and in 1687 he became superior of the province. A false accusation of complicity in an assassination, and the intrigues of members of his own Company, clouded his last months, and on July 18, 1697 he died in Salvador, Bahia.

His works form perhaps the greatest monument of Portuguese prose. Two hundred discourses exist to prove his fecundity, while his versatility is shown by the fact that he could treat the same subject differently on half a dozen occasions. His letters, simple and conversational in style, have a deep historical and political interest, and form documents of the first value for the history of the period.