HAPPY FRIDAY, P.O.U.!

CONISTON MASSACRE

Northern Territory, Australia

August 14 – October 18 1928

The Coniston massacre, which took place from 14 August to 18 October 1928 near the Coniston cattle station in Northern Territory, Australia, was the last known massacre of Indigenous Australians and one of the last events of the Australian Frontier Wars. People of the Warlpiri, Anmatyerre and Kaytetye groups were killed. The massacre occurred in revenge for the death of dingo hunter Frederick Brooks, killed by Aborigines in August 1928 at a place now known as Yukurru, (also known as Brooks Soak).

Official records at the time stated that 31 people were killed. The owner of Coniston station, Randall Stafford, was a member of the punitive party for the first few days and estimated that at least twice that number were killed between 14 August and 1 September. Historians estimate that at least 60 and as many as 110 Aboriginal men, women and children were killed.[1] The Warlpiri, Anmatyerre and Kaytetye believe that up to 170 died between 14 August and 18 October.[2]

Background

For administrative reasons, from 1927 to 1931, the Federal Government divided the Northern Territory into North (population 4,000) and Central Australia (population <500). By July of 1928 (mid-winter), Central Australia was in its fourth year of a particularly severe drought with fewer than 25 millimetres (0.98 in) of rain falling in the previous seven months. Overgrazing by stock had denuded the country of its vegetation, leaving little feed for wildlife. Waterholes were drying up and even the most experienced Aborigines were finding game and water almost unobtainable. Almost all the permanent waterholes and soaks were on station properties and as Aborigines began to die from thirst and hunger they moved to the stations for the water where they became an “aggravation” by begging for food and spearing cattle. The pastoralists chased the Aborigines away from their water to ensure the survival of their cattle.[3]

Sixty-seven-year-old Fred Brooks had worked as a station hand on Randall Stafford’s Coniston station, 240 mi (390 km) north-west of Alice Springs, since the end of World War I, but due to the drought had not been paid for some time. In July 1928 he bought two camels and on 2 August, left with two 12 year-old Aboriginal children, Skipper and Dodger, to trap dingoes for the 10s (2011:A$35.65) bounty on their scalps. Approaching a soak 14 mi (23 km) from the homestead, he found around 30 Ngalia-Warlpiri people camped. Brooks knew some and decided to camp with them. The first two days were uneventful and Brooks caught several dingoes. On 4 August, Charlton Young and a companion who were exploring the area for a mining company, stopped by and warned Brooks that the Aborigines had been getting “cheeky” lately by visiting the mining camps heavily armed, demanding food and tobacco. Brooks had been approached several times to trade but had so far refused. On 6 August, Bullfrog with his wife Marungali asked him to trade and Brooks offered some food in exchange for Marungali washing his clothes. Bullfrog camped nearby but Brooks neither paid him the promised food nor did he return his wife. In the morning Bullfrog became enraged when he found his wife in bed with Brooks and attacked him, severing an artery in his throat with his boomerang. Bullfrog, his uncle Padirrka and Marungali then beat Brooks to death. Aboriginal elders fearfully banished Bullfrog and Padirrka and ordered Brooks’ two boys to return to the homestead and say that he had died of natural causes.[notes 1] The following day an Aborigine named Alex Wilson camped at the now deserted soak and finding the body rode back to the station, where he described hysterically how Brooks had been “chopped up” by 40 Aborigines and the parts stuffed in a rabbit burrow.[3]

Randall Stafford had been in Alice Springs requesting police to attend to prevent the spearing of his cattle. He returned to be told of the murder and “dismemberment” of Brooks but chose to wait for the police. No one returned to the soak and no one attempted to retrieve the body. On 11 August, the Government Resident J. C. Cawood sent Constable William Murray, the officer in charge at Barrow Creek who also held the post of Chief Protector of Aborigines,[notes 2] to Coniston to investigate the complaints of cattle spearing. Told of the murder, Murray drove back to Alice Springs and telephoned Cawood who refused to send reinforcements, telling Murray to deal with the Aborigines as he saw fit. Returning to Coniston, Murray questioned Dodger and Skipper who described the circumstances of the murder and named Bullfrog, Padirrka and Marungali as the killers. According to his own report, Murray also obtained the names of 20 accomplices (he never recorded the names, or explained how his informants, who were not eye-witnesses, knew them; nor were these inconsistencies ever questioned at later proceedings). Murray organised a posse consisting of tracker Paddy, Alex Wilson, Dodger, tracker Major (elder brother of Brooks’ boy Skipper), Randall Stafford and two white itinerants Jack Saxby and Billie Brisco.[notes 3][4]

Massacre

Brooks was killed on or about 7 August 1928, and his body was partly buried in a rabbit hole in the Northern Territory. No eyewitnesses to the actual murder were ever identified, and there are conflicting accounts of the discovery of the body and subsequent events.

On 15 August, dingo trapper Bruce Chapman arrived at Coniston and Murray sent Chapman, Paddy and Alex Wilson to the soak to find out what happened. The three buried Brooks on the bank of the soak.[notes 4] In the afternoon two Warlpiri, Padygar and Woolingar arrived at Coniston to trade dingo scalps. Believing them to be involved with the murder Paddy arrested them but Woolingar slipped his chains and attempted to escape. Murray fired at Woolingar and he fell with a bullet wound to the head. Stafford then kicked him in the chest breaking a rib. Woolingaar was then chained to a tree for the next 18 hours. The next morning the posse, with Padygar and Woolingar following on foot in chains, set out for the Lander River where they found a camp of 23 Warlpiri at Ngundaru. With the posse encircling the camp, Murray rode in and was surrounded by Aborigines yelling, Brisco started shooting with Saxby and Murray joining in. Three men and a woman, Bullfrog’s wife Marungali, were killed with another woman dying from her wounds an hour later, a search of the camp turned up articles belonging to Brooks. Stafford was furious with Murray over the shooting and the next morning returned to Coniston alone.[4]

During the night, Murray captured three young boys who had been sent by their tribe to find what the police party was doing. Murray had the boys beaten to force them to lead the party to the rest of the Warlpiri but had they done so, they would have been punished by their tribe. To resolve the dilemma, the three boys smashed their own feet with rocks. Despite the injuries Murray forced the now crippled boys to lead the party.[5] By nightfall they reached Cockatoo Creek where they sighted four Aborigines on a ridge. Paddy and Murray captured two but one ran with Murray firing several shots at him which missed, Paddy then knelt and fired a single shot hitting the fleeing man in the back and killing him instantly. After questioning the other three and finding they had no connection with the murder Murray released them. The next two days saw no contact with Aborigines at all as word had spread with many Aborigines heading into the desert, preferring to risk dying of thirst, rather than face the police patrol. Returning to Coniston, Murray left Padygar, Woolingar and one of the three boys, 11 year-old Lolorrbra (known as Lala, he became a chief witness at the enquiry), whose crushed feet had become infected, in Stafford’s custody before heading north to continue the search.[4]

Following tracks, the patrol came upon a camp of 20 Warlpiri, mostly women and children. Approaching the camp Murray ordered the men to drop their weapons, not understanding English the women and children fled while the men stood their ground to protect them. The patrol opened fire killing three men; three injured died later of their wounds and an unknown number of wounded escaped. By Murray’s account, he met four separate groups of Warlpiri, and in each case was obliged to shoot in self-defense – a total of 17 casualties. He later testified under oath that each one of the dead was a murderer of Brooks. The Warlpiri themselves estimated between 60 and 70 people had been killed by the patrol.[4]

On 24 August, Murray captured an Aborigine named Arkirkra and returned to Coniston where he collected Padygar (Woolingar had died that night still chained to the tree) and then marched the two 240 mi (390 km) to Alice Springs. Arriving on 1 September, Arkirkra and Padygar were charged with the murder of Brooks while Murray was hailed as a hero.[4] On 3 September, Murray set off for Pine Hill station to investigate complaints of cattle spearing. Nothing has been recorded about this patrol, but he returned on 13 September with two prisoners. On 16 September, Henry Tilmouth of Napperby station shot and killed an Aborigine he was chasing away from the homestead, this incident was included in the later enquiry. On the 19th, Murray again departed, this time under orders to investigate a non-fatal attack on the person of a settler, William Nuggett Morton, at Broadmeadows Station by what Morton described as a group of 15 Myall Warlpiri people who were also in the same area.

Morton, a former circus wrestler, had a reputation for his sexual exploitation of Aboriginal women and violence against both his white employees and Aborigines.[4] On 27 August, he left his camp to punish Aborigines for spearing his cattle.[4] At Boomerang waterhole he found a large Warlpiri camp, what happened here is unknown but the Warlpiri decided to kill Morton. During the night they surrounded his camp and at dawn 15 men armed with boomerangs and yam sticks rushed Morton. His dogs attacked the Aborigines and after breaking free Morton shot one and the rest fled. Morton returned to his main camp and was taken to the Ti Tree Well mission where a nurse removed 17 splinters from his head and treated him for a serious skull fracture.[4]

From the station, on 24 September, a party consisting of Murray, Morton and half-castes Alex Wilson and Jack Cusack, embarked on a series of encounters (three incidents were later described by Murray in which 14 more Aborigines were killed, but it is likely there were more). At Tomahawk waterhole four were killed, while at Circle Well one was shot dead and Murray killed another with an axe. They then moved east to the Hanson River where another eight were shot. Morton identified all of them as his attackers. The party now returned to Broadmeadows to replenish their supplies before travelling north. No records of this patrol were kept. According to the Warlpiri, this patrol encountered Aborigines at Dingo Hole where they killed four men and 11 women and children. The Warlpiri also recount how the patrol charged a corroboree at Tippinba, rounding up a large number of Aborigines like cattle before cutting out the women and children and shooting all the men.[6] There is anecdotal evidence that there were up to 100 killed in total at the five sites.[4]

Constable Murray was back in Alice Springs on 18 October where he was asked to write an official report on the police actions. The report was only several lines long, he wrote: “….incidents occurred on an expedition with William John Morton, unfortunately drastic action had to be taken and resulted in a number of male natives being shot.” No mention was made of the number killed, the circumstances of the shootings or where they occurred.[7]

Trial of two Aborigines

The trial of Arkirkra and Padygar for Brooks murder took place in Darwin on 7 and 8 November before Justice Mallen.

The first witness was 12 year-old Lolorrbra (known as Lala) who testified in detail that he saw Arkirkra, Padygar and Marungali kill Brooks. He also testified that all the Aborigines that had helped them were now dead. Constable Murray took the stand next, his evidence becoming so involved in justifying his own actions in killing suspects that Justice Mallen reminded him that he himself was not on trial and to avoid facts not relevant to the guilt of the accused. The court then adjourned for lunch. The verdict was a foregone conclusion as all that remained was the reading of the confessions made by the accused in Alice Springs. Despite lunch for the jurors being provided by the local hotel, two of the jurors went home to eat. A furious Justice Mallen dismissed the jury, ordered a new jury be empanelled and a new trial to be convened the following day. The new trial began with Lolorrbra being asked to repeat his evidence. This time his evidence, although still maintaining that the accused were the murderers, was completely contradictory. Under cross examination it became apparent within minutes that he had been coached on what to say. When the prosecution tried to introduce the written confessions of the accused, Justice Mallen pointed out that as the accused had been charged by a South Australian rather than Central Australian magistrate he would disallow the statements. The prosecution declined to call the accused to testify. Murray took the stand next, angering Justice Mallen when he repeated his justifications for killing suspects. The judge remarked “It appears impossible for all those bands of natives to be associated with the murder of Brooks. It looks as if they were shot down at different places just to teach them and other aborigines a lesson.”[8] With no evidence of guilt presented, Justice Mallen ordered the jury to acquit the accused.[9]

During his testimony, Murray said that the group had “shot to kill”:

Justice Mallen: Constable Murray, was it really necessary to shoot to kill in every case? Could you not have occasionally shot to wound?

Murray: No your honour, what is the use of a wounded blackfellow hundreds of miles from civilization?

Justice Mallen: How many did you kill?

Murray: Seventeen your honour.

Justice Mallen: You mean you mowed them down wholesale!—The Northern Territory Times, 9 November 1928[4]

In the courtroom to hear this and other evidence of massacre was Athol McGregor, a Central Australian missionary. He passed on his concern to church leaders, and eventually to William Morley, outspoken and influential advocate of the Association for the Protection of Native Races, who did the most to secure a judicial enquiry. The Federal government was also under considerable pressure to act. The British media had been reporting on Australia’s treatment of Aborigines (Australia was in financial difficulties at the time and an economic mission from London was considering financial assistance), a federal election was due on 17 November and the League of Nations had publicly criticized the case.[10]

During the trial Murray was billeted with the Northern Territory police. Although Murray officially admitted to only 17 deaths, Constable Victor Hall said he was shocked with Murray’s “freely expressed opinions of what was good enough for a blackfellow”, and claimed he bragged to fellow officers that he had killed “closer to 70 than 17”.[4][11]

Board of Inquiry

The Board of Inquiry was presided over by police magistrate A. H. O’Kelly and was deeply compromised from the start – its three members being hand-picked to maximise damage control; J. C. Cawood, Government Resident in Central Australia, and Murray’s immediate superior, being one of them. Cawood revealed his own disposition in a letter to his departmental secretary shortly after the massacre: “…trouble has been brewing for some time, and the safety of the white man could only be assured by drastic action on the part of the authorities … I am firmly of the opinion that the result of the recent action by the police will have the right effect upon the natives.”[12]

The board sat for 18 days in January 1929 to consider three incidents (Brooks, Morton and Tilmouth) that resulted in the deaths of Aborigines, and in one more day, finished its report, finding that 31 Aborigines had been killed and that in each case the death was justified.

The hearing decided, in the face of indubitable evidence to the contrary, that there had been no drought in Central Australia, evidence of ample native food and water supplies and thus no mitigation for cattle spearing. A journalist for the Adelaide Register-News who travelled with the board during its tour of Central Australia to determine the claims of drought reported; “Five years of drought have burnt every blade of grass from the plains and left a wilderness of red sand…the wonder is that any living thing survives. Every settler visited by the Board had lost between 60 to 80 percent of his stock [to the drought] this year alone.” The day after this report was published, a settler replied in the letters to the editor that the drought made the life of one ewe worth more to Australia than “all the blacks that were ever here”.[13]

Cawood expressed his satisfaction with the outcome in his annual report for 1929, writing: “The evidence of all the witnesses was conclusive … the Board found that the shooting was justified, and that the natives killed were all members of the Walmulla (sic) tribe from Western Australia, who were on a marauding expedition, with the avowed object of wiping out the white settlers…”[14]

Following his appointment, O’Kelly had stated his intention that the enquiry would not be a whitewash and it is speculated he had been “got at.” To take up his appointment, O’Kelly travelled by train from Canberra to Melbourne with Prime Minister Stanley Bruce, who was campaigning for the upcoming election with the White Australia policy as his party’s main platform, accompanying him. O’Kelly later said that had he known how the enquiry would turn out, he would have refused the appointment, stating that if the same circumstances happened again someone would be hanged for the killings.[15]

Reporting on the inquiry, the Adelaide Register-News wrote: “he [Murray] is the hero of Central Australia. He is the policeman of fiction. He rides alone and always gets his man.”[4] The Northern Territory Times announced that the police were wholly exonerated, and that “there was not a scintilla of evidence” to support the view that the police had conducted a reprisal or punitive expedition.[16]

Aftermath

Constable Murray was quietly removed from his position and moved to Adelaide where he died in the 1960s. William Morton moved out of the area several years after the massacre. Bullfrog was never arrested and moved to Yuendumu where he died of old age in the 1970s.[4]

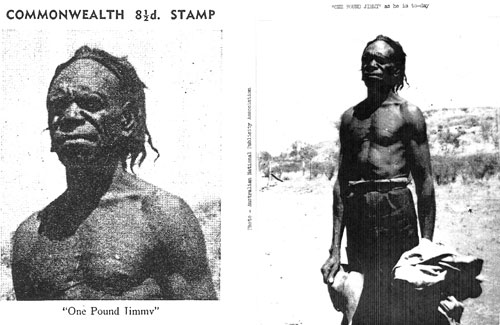

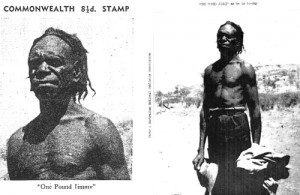

One of the few survivors was Gwoya Jungarai, who left the area after the massacre destroyed his family. A later picture of him as One Pound Jimmy became an iconic Australian postage stamp.

Billy Stockman Tjapaltjarri, a prominent Papunya Tula painter, was a survivor of the massacre. His father was away hunting and survived while his mother had hidden him in a coolamon under a bush before being shot and killed.[17] The strong oral history established after the massacre is recorded in paintings by some indigenous artists and the Warlpiri, Anmatyerre and Kaytetye refer to the period as The Killing Times. Similarly, other massacres that have occurred in the Ord River region have been recorded by Warmun artists such as Rover Thomas.

Seventy-fifth anniversary

Member of the Northern Territory Legislative Assembly, John Ah Kit in an adjournment debate on 9 October 2003 stated:[18]

It must be remembered that the late 1920s was a time of major drought and therefore, in the context of what was still very much the frontier of black/white relations in Australia, the conflict over resources was intense. It was a conflict between the land and its people; and the cattle, and those who had brought with them the guns and diseases that followed. What is often misunderstood is that the Coniston Massacre was no single event, but a series of punitive raids that occurred over a number of weeks as police parties killed indiscriminately. Even Keith Windschuttle, one of the great deniers of frontier violence, acknowledges the savagery and disproportionate nature of the Coniston reprisals. Even he, albeit based only on the unsubstantiated writings of a journalist, agrees that many more died than the official record will admit.

The seventy-fifth anniversary of the massacre was commemorated on 24 September 2003 near Yuendumu organised by the Central Land Council.[19]

Documentary film

In 2012, a docu-drama film titled Coniston was released by PAW Productions and Screen Australia. It presented oral history and recollections of elderly Aborigines, including descendants of massacred victims. Directed by David Batty and Francis Jupurrurla Kelly, it was aired throughout Australia by ABC1 on 14 January 2013.[20]