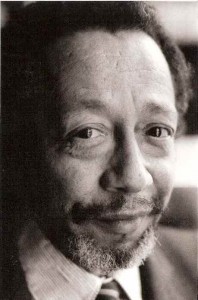

The bebop musician I am highlighting today, had a very interesting story. Nii-lante Augustus Kwamlah Quaye, better known as Cab Kaye ( September 3, 1921, London – March 13, 2000, Amsterdam), was an English-born Ghanaian-Dutch jazz singer, pianist, bandleader, entertainer, drummer, guitarist and songwriter who was influenced by Billie Holiday and often accompanied himself on piano with a graceful, rhythmic style. He effortlessly combined blues, bebop,stride and scat with the music of his African and Ghanaian musical heritage.

Don’t You Go Away

Cab Kaye, also known as Cab Quay, Cab Quaye and Kwamlah Quaye, was born on St. Giles High Street in Camden, London to a musical family. His Ghanaian great-grandfather was an asafo warrior drummer and his grandfather, Henry Quaye, was an organist for the Methodist Mission church in the former Gold Coast, now called Ghana. Cab’s mother, Doris Balderson, sang in English music halls and his father, Caleb Jonas Quaye (born 1895 in Accra, Ghana), performed under the name Ernest Mope Desmond as musician, band leader, pianist and percussionist. With his blues piano style, Caleb Jonas Quaye became popular around 1920 in London and Brighton with his band “The Five Musical Dragons” in Murray’s Club with, among others, Arthur Briggs, Sidney Bechetand George “Bobo” Hines.

When Cab Kaye was only four months old, his father was killed in a railroad accident in January 1922, on his way to perform in a concert. Cab, his mother and his sister, Norma, moved to Portsmouth, where a life insurance policy provided temporary financial support. Between the ages of nine and twelve he spent three years in hospital while a tumor in his neck was irradiated. British radiation therapy was still in its infancy and Kaye’s treatment was experimental. A permanent scar remained on the left side of his neck.

His first instrument was the timpani; a Canadian soldier introduced him to this instrument and taught him how to count and use the mallets. At fourteen, Kaye began to visit nightclubs where coloured musicians were welcome, for example the “Shim Sham” and “The Nest”; he eventually won first prize in a song contest, a tour with the Billy Cotton band. During this tour, he met the African-American trombonist and tap dancer Ellis Jackson. Jackson convinced Cotton to engage Cab as an assistant, and as a singer in his band. Originally engaged as a tap dancer with Billy Cotton’s show band in 1936, Cab recorded his first song, “Shoe Shine Boy” under the name Cab Quay.

Everything is Go

In 1937 Cab Kaye played drums and percussion with Doug Swallow and his band in April, the Hal Swain Band in the summer and Alan Green’s band in September in Hastings, England. Until 1940 he sang and drummed with the Ivor Kirchin Band, with Steve Race on piano, in the Paramount Dance Hall (on Tottenham Court Road), where he was one of the only Africans around. When a guest was refused entrance because of skin colour, Kaye refused to perform. The incident led to the regular acceptance of people of colour and the Paramount Dance Hall grew into a sort of “Harlem of London”. After a short period with Britain’s first black swing bandleader, Ken “Snakehips” Johnson and His Rhythm Swingers, Kaye played in several radio broadcasts. Shortly thereafter, he joined the British Merchant Navy, which was required to sail and provided support services to the allies during World War II. On 8 March 1941, three days after Kaye enlisted, Ken “Snakehips” Johnson and saxophonist David Williams were killed when a bomb fell on the Café de Paris nightclub in London’s West End, where they were performing. Around this time Kaye’s mother was also killed when her house in Portsmouth was the only house on her street to be hit by a bomb.

While on leave from the Merchant Navy, Kaye sang with Don Mario Barretto in London. In 1942, his ship was hit by a torpedo in the Pacific Ocean. Kaye was saved, but his convoy continued to be attacked by enemy ships. During the following three nights, two other ships were sunk. These experiences stayed with Cab for the rest of his life and explain his constant fear of fireworks. But the adventure was not over. En route to an Army hospital in New York he was badly hurt as his plane crashed just before landing. While recuperating in New York, he went to concerts and played in clubs in Harlem and Greenwich Village with the trumpet player Roy Eldridge, trombonist Sandy Williams, Slam Stewart, Pete Brown, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Willie “The Lion” Smith.

Sweet Lorraine

In 1946, Cab Kaye sang for the British troops in Egypt and India with Leslie “Jiver” Hutchinson’s “All Colored Band”. After that, he performed as a singer and entertainer in Belgium. In 1947, he returned to London to sing in the bands of guitarist Vic Lewis, trombonist and bandleader Ted Heath, the bebop accordionist Tito Burns and the band “Jazz in the Town Hall”. From 1948 he performed mainly as orchestra leader of his own bands, such as “The Ministers of Swing”. For the new wave of London musicians from the West Indies, as well as the English musicians, Kaye was an inspiration as bandleader.

In this period he also led “Cab Kaye and his Coloured Orchestra” and co-led “The Cabinettes” with Ronnie Ball, featuring “blues singer” Mona Baptiste from Trinidad. Both of these bands played regularly in the Fabulous Feldman Club (100 Oxford Street, London), featuring Kaye on electric guitar. Kaye’s band was, in 1948, the first musical ensemble featuring people of colour to play in Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw. In Paris at the end of the 1940’s early 1950’s, Kaye met Tadd Dameron, who was then playing with Miles Davis. Dameron gave Kaye his first and only piano lesson. In the Club St. Germain, Kaye played with guitarist Django Reinhardt, who had become more interested in bebop.

Between December 1950 and May 1951, Cab Kaye’s Latin American Band, booked by Lou van Rees, toured France, Germany and The Netherlands (where Kaye met Charlie Parker, among other notables). In the Netherlands, Kaye played in the newly opened “Avifauna” in Alphen aan den Rijn, the world’s first bird park. In a turn of fate, he first met his later wife Jeannette at Avifauna when she was a little girl. The reprise came 30 years later when Cab and Jeannette married.

Meanwhile, Kaye led various multi-ethnic bands, usually consisting of musicians from British, African and West Indian origin. Later that year, he was in the revue entitled “Memories of Jolson”, a musical based on the life of Al Jolson, featuring sixteen-year-old Shirley Bassey. The show toured Scotland but Kaye pulled out after the first performance on the grounds of its racism. Kaye decided to focus increasingly on variety shows and he founded the theatre booking agency Black and White Productions Ltd, to book small theatre and film roles for himself and other musicians. His career as a businessman did not last long and he soon concentrated again on making music.

A July 1953 flyer from Jephson Gardens Pavilion announced Cab Kaye and his orchestra with a special attraction: “America’s Queen of the Ivories”, Mary Lou Williams. In this band he accompanied the jitterbug and tap dancer Josephine (Josie) Woods, Dizzy Reece (trumpet), Pat Burke (tenor sax), Dennis Rose (piano), Denny Coffey (bass) and Dave Smallman (bongo & conga) in “Cab Kaye’s jazz septet” among others at the London Palladium in 1953. Several different types of appearances followed, including performances with “Old Black Magic” singer Billy Daniels and pianist Benny Payne.

In March 1957, the Gold Coast became Ghana, the first sub-Saharan African country to gain its independence. Three years later, in March 1960, Kwame Nkrumah became president of the republic. For Cab Kaye, Ghana’s independence was an important political symbol. Two family members in high government positions, Tawia Adamafio and C. T. Nylander, had brought Kaye into contact with Ghanaian politics. After Independence, during Nkrumah’s reign, Kaye was appointed the Government Entertainments Officer and from 1961 worked at the Ghana High Commission in London as protocol officer. As such he played a role in getting a Ghana passport for Miriam Makeba, whose South African passport had been revoked under the country’s apartheid regime.

Probably partly influenced by both racist experiences and euphoria over Ghana’s Independence, he discarded with the anglicised version of his name (Cab Kaye) and called himself Kwamlah Quaye (some newspapers forgot the “h” in Kwamlah).