Good Morning POU!! Today we highlight the man known as the best stagecoach driver in the West. He was also one of the first black Pony Express drivers.

The man who would become renowned for driving stagecoaches — and three U.S. presidents — into Yosemite Valley started life in Georgia and headed West at the age of 11.

In stagecoach days, drivers carried Wells Fargo treasure shipments and passengers across the frontier. It took skill to drive a coach and Wells Fargo added rigorous standards of its own: superior reinsmanship, self-reliance and upstanding character.

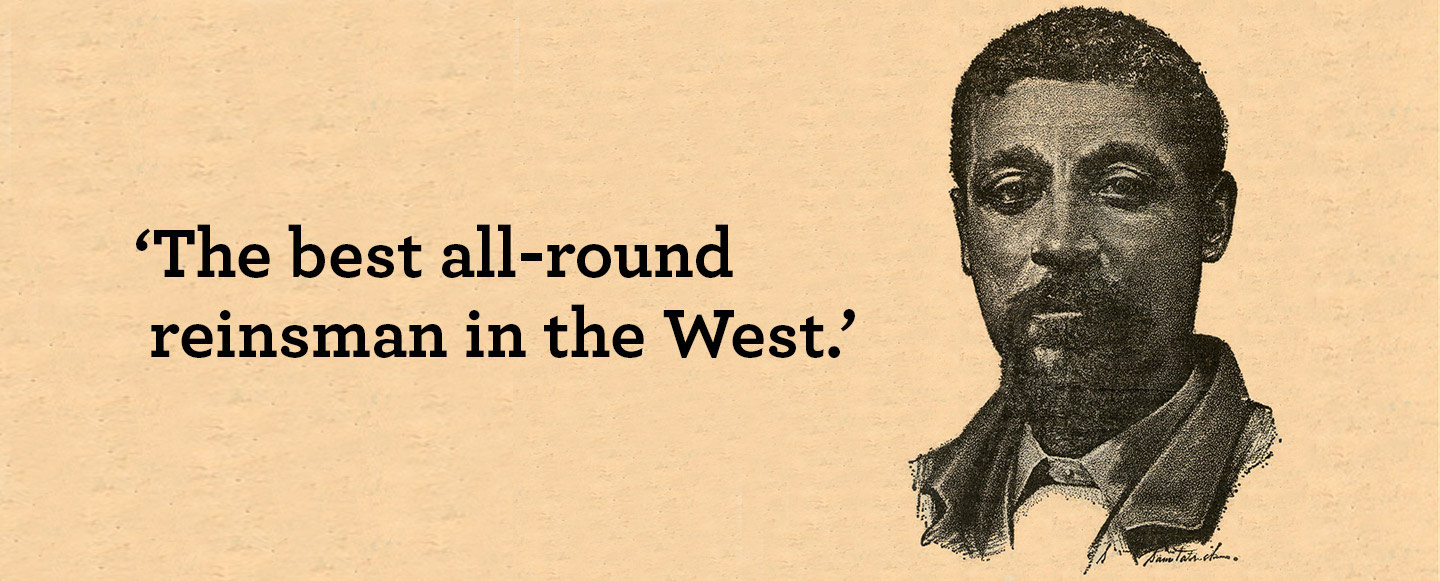

In 1855, 11-year-old George Monroe came west from Georgia. When Monroe had grown, he came to exemplify the greatness of fact and legend of the best stagecoach drivers. He was described by his employers as “the best all-round reinsman in the West.”

Early on, George Monroe exhibited a knack for training and driving horses. At age 22, he took a job driving for the A.H. Washburn and Company stage line into Yosemite. That stage line carried passengers and Wells Fargo & Co.’s Express into Yosemite Valley. Monroe expertly navigated the treacherous cliffside roads into the Valley and became the best driver around.

One time, the brakes of Monroe’s coach failed between Mariposa and Merced while full of passengers. Monroe stayed cool, and at an opportune moment drove his team into a clump of brush, bringing the stage to a safe halt. Grateful passengers passed the hat and presented Monroe with $70.

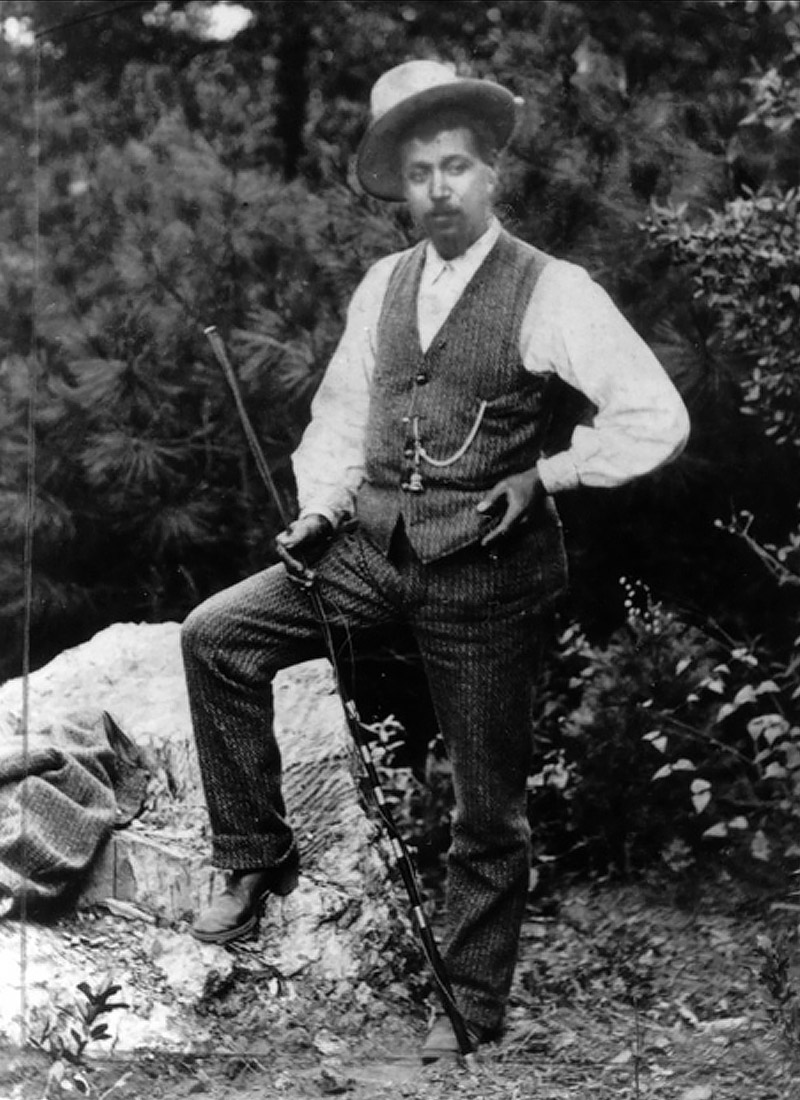

His expertise garnered him the nickname of “Knight of the Sierras.” He was described as alert, mild-mannered, and well-dressed, always wearing white gauntlets embroidered in silk, an expensive hat, and boots that shined like mirrors.

In 1879, the celebrated Monroe was asked to carry a fellow celebrity into Yosemite — Ulysses S. Grant, 18th President of the United States. Grant’s schedule took him and Mrs. Grant down the dangerous, 26-mile route into Yosemite Valley, with hairpin turns and fallen rocks and chuckholes. There was a stretch so narrow, the stagecoach’s wheels brushed against the granite walls of the cliff. Inches from the other wheels was a thousand-foot gorge.

The crusty general chose to sit next to the driver, a place of honor in those days. An expert horseman in his own right, Grant’s assessment of Monroe’s skills would make or break his reputation as a stagecoach driver. Monroe did his magic and Grant was duly impressed: “He would throw those six animals from one side to the other,” the president marveled, “to avoid a stone or a chuckhole as if they were a single horse.”

As for his role on the Pony Express, it was said that George F. Monroe was hired by Division Superintendent Bolivar Roberts. His route would Merced to Mariposa that ran for 140 miles. According to one account, Monroe had to run a judicial order to Mariposa to keep the sheriff from releasing outlaw Johnny Edmonds. It appears that Edmonds had murdered a bank teller and was to be held for trial.

The route ran through treacherous territory and a known gang was on the prowl waylaying dispatchers. Just 25 miles shy of Mariposa he ran into the Edmonds gang yet managed to escape.

By 1885, Monroe had driven two more Presidents to Yosemite: James A. Garfield and Rutherford B. Hayes, as well as Gen. William T. Sherman. George Monroe died in 1886 when a stagecoach overturned and mortally injured him. Ironically, Monroe was not the driver, but a passenger — it’s a good bet he’d have avoided the accident entirely if he had been “in the box” as driver.

Fort Monroe in Yosemite National Park was named after George Monroe.