Good Morning POU!

![]()

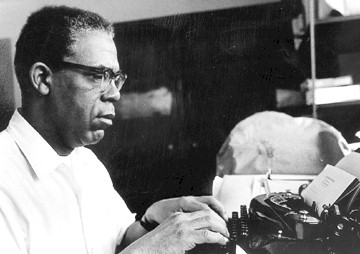

Today we feature perhaps, the single most important person that provided black poets and authors an avenue for their works during the Black Arts Movement. Some of the most influential and powerful works of the era would not have been published if not for Dudley Randall and Broadside Press.

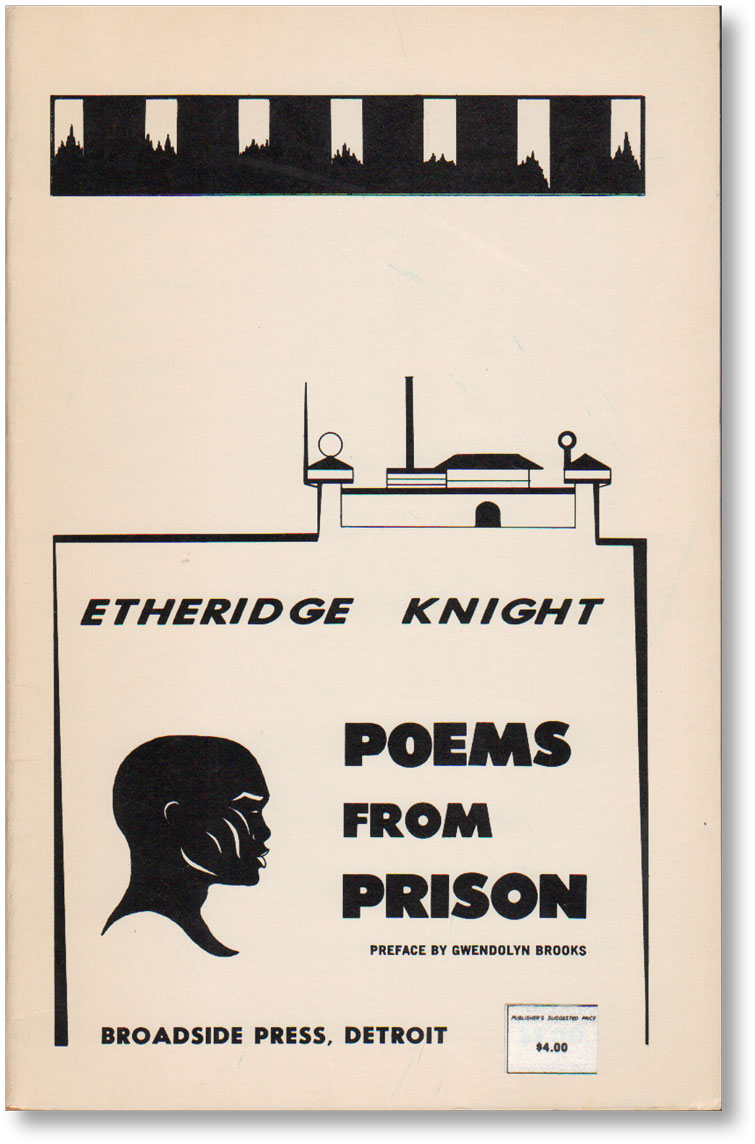

Dudley Randall (January 14, 1914 – August 5, 2000) was an African-American poet and poetry publisher from Detroit, Michigan. He founded the pioneering publishing company Broadside Press in 1965, which published many leading African-American writers, among them Melvin Tolson, Sonia Sanchez, Audre Lorde, Gwendolyn Brooks, Ethredige Knight, Margaret Walker and many more. Randall’s most famous poem is “The Ballad of Birmingham,” written in response to the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, in which four girls were killed. Randall’s poetry is characterized by simplicity, realism, and what one critic has called the “liberation aesthetic”.

Randall was born in Washington D.C.,the son of Arthur George Clyde (a Congressional Minister) and Ada Viola Randall (a teacher). His family moved to Detroit in 1920, and he married Ruby Hudson in 1935, however, this marriage dissolved. Randall married Mildred Pinckney in 1942, but this marriage did not last either. In 1957, he married Vivian Spencer.

Randall developed an interest in poetry during his school years. At the age of thirteen, his first published poem appeared in the Detroit Free Press. He attended Wayne State University in Detroit, where he earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in English in 1949. Randall then completed his master’s degree in Library Science at the University of Michigan in 1951. He worked as a librarian at Lincoln University and also Morgan State College in Baltimore. In 1956, he returned to Detroit to work at the Wayne County Federated Library System as head of the reference-inter loan department. From 1969-1976 Mr. Randall was a reference librarian at the University of Detroit (now the University of Detroit Mercy), and served also as the University’s Poet-in-Residence.

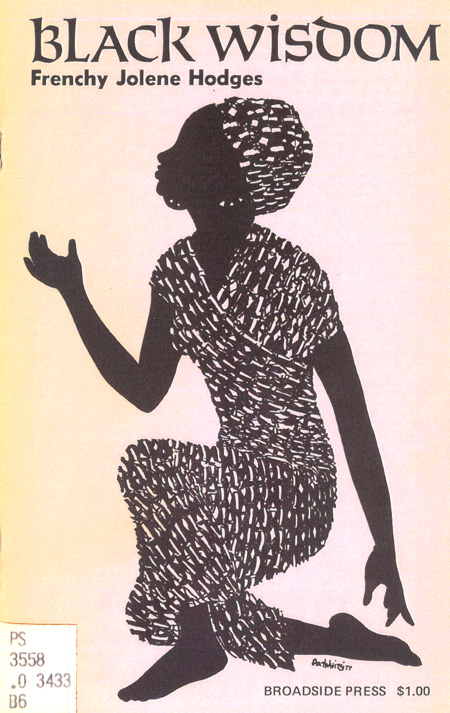

It was in 1965 that Randall founded Broadside Press. The press was run out of his home, with limited funds, but managed to publish the major African-American poetry of the time. The list of new and established poets published by Broadside Press is impressive and exposed Black Americans to artists and poets that are now household names. Randall founded Broadside Press to publish his own poetry but soon expanded to include other poets with focus on producing inexpensive but quality broadsides and books. All profits from the sales were put back into the company as Randall supported himself with his position as librarian at the University of Detroit. In 1978 Black Enterprise magazine called Randall, “The father of the black poetry movement.”

Broadside Press really took off when, during the 1965 Writer’s Conference at Fisk University, Randall saw Margaret Walker practicing her recitation of a poem about Malcolm X she was going to perform. When Randall commented on the quantity of poems being published about Malcolm, Margaret Burroughs suggested the idea of an anthology. Randall and Burroughs communicated their intentions to edit a book of poetry on Malcolm X at the conference, and their fellow poets and publishers responded enthusiastically, some even refusing to be paid for their work.

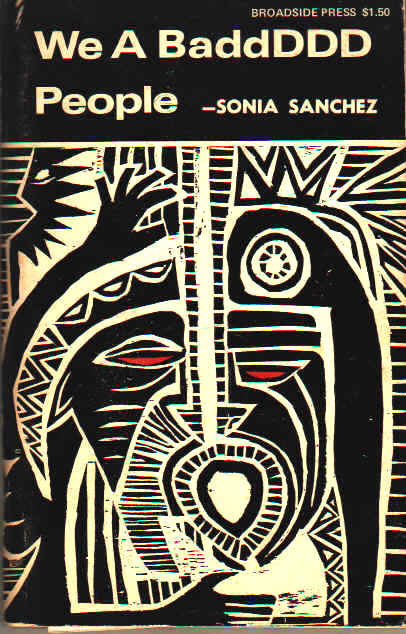

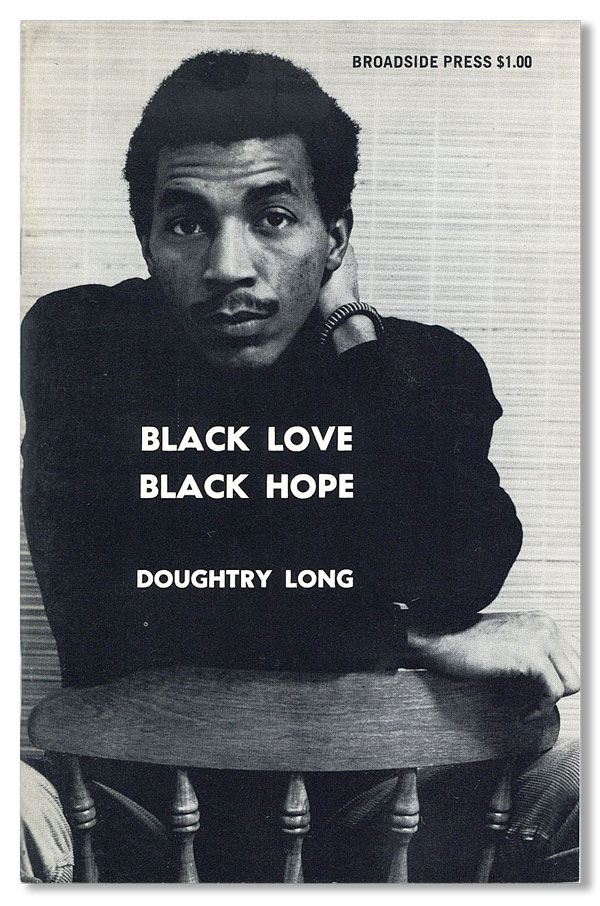

Broadside Press published poetry almost exclusively, with more than 400 poets represented and more than 100 books and recordings released. The press has the distinction of being one of the most important literary avenues of the Black Arts Movement, as well as presenting older black poets (like Gwendolyn Brooks) and emerging voices (like Nikki Giovanni and Sonia Sanchez) to new readers.

As editor of the Broadside Press, Randall was key to the power of the Black Arts Movement as well as the freedom of black poets to express themselves in whatever way they were moved. The aesthetic counterpart of the political drive inherent in the Black Power movement, BAM rejected assimilation in favor of artistic and political freedom. Part of the movements doctrine was a belief in the necessity of militant armed self-defense and the beauty and goodness of Blackness. BAM poets were known for an innovative use of language, particularly focusing on orality and the use of Black English, music, and performance for a full-bodied, authentic“black experience” that rejected white literary standards.

Although Randall was a proponent of the freedom BAM offered black poets, particularly up-and-coming artists, he was not afraid to question what he saw as inherent paradoxes within the movement. For Randall, both the overtly militant aesthetic and the desire to purify poetry of white characteristics were restrictive to the expression of black artistry. Randall viewed himself as the “guardian of a poetic space out of which black poets may create without restriction.”

Dudley Randall died in 2001 and his impact is still felt today. Poets from across the country came to honor the man who gifted so many black writers with the chance to showcase their talents to the world.

Most of all, people remembered him as the man who built a publishing company that helped lay the foundation for much of the success of today’s African-American writers.

“Broadside Press was bigger in terms of impact than just the specific books,” said Melba Boyd, a Broadside Press poet and head of Wayne State University’s Africana Studies department. “As an independent press that was successful but small compared to mainstream (publishers), it opened up the literary canon, and now mainstream publishers began publishing poetry and black writers and other minority writers. It … changed the whole character of American literature.”

Randall was the other Berry Gordy, the one who never left the west side of Detroit, never made millions and never became a glitter-sprinkled celebrity. Yet he, too, beamed black voices around the world, receiving a Lifetime Achievement Award in 1996 from the National Endowment for the Arts.

His stars weren’t slinky singers or coordinated crooners. Randall showcased previously unpublished poets and national figures such as Nikki Giovanni, Sonia Sanchez, LeRoi Jones, Alice Walker and Haki Madhubuti.

Pulitzer-prize-winning poet Gwendolyn Brooks left Harper and Row to become a Broadside poet. And Audre Lorde’s 1973 Broadside book, From a Land Where Other People Live, was nominated for a National Book Award.

Like Berry Gordy, who boxed and worked on an assembly line before founding Motown, Randall didn’t become a legend overnight. He worked for Ford, and labored at the post office while earning degrees in English and library science. According to the often-told story, Gordy set up Motown with an $800 loan from his family. Randall began his publishing career with $12.

However, Randall became a publisher by chance. In response to a 1963 church bombing in Alabama, he wrote”The Ballad of Birmingham,” and his poem was set to music and recorded by a folk singer. To protect his rights, Randall had it printed on a single sheet, or broadside, in 1965. That was the start of Broadside Press.

The Press grew “by hunches, intuitions, trial and error,” Randall once wrote, until it had published 90 titles of poetry and had printed 500,000 books. In his spare bedroom, Randall licked stamps and envelopes, packed books, read manuscripts, wrote ads and planned and designed books.