Good Morning POU!

The desire to be free is, of course, human and universal. In America, enslaved people had tried to escape through the Underground Railroad. Later, once freed on paper, thousands more, known as Exodusters, fled the violent white backlash following Reconstruction in a short-lived migration to Kansas in 1879.

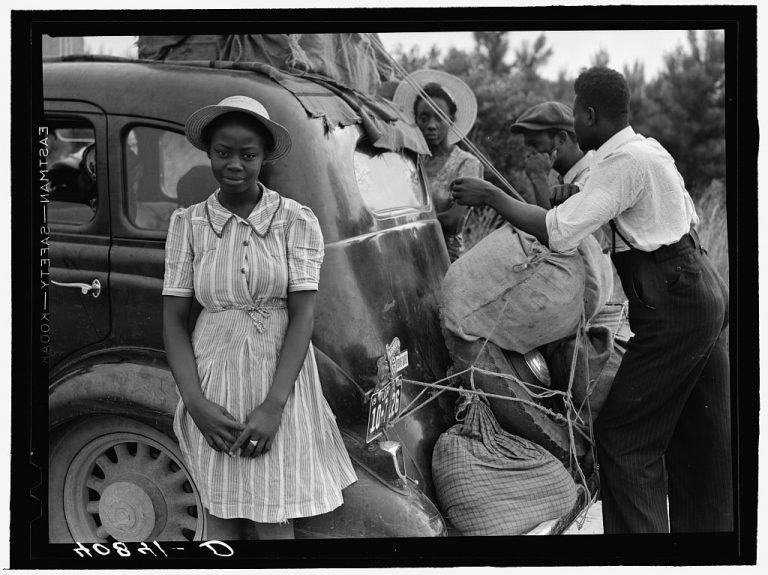

But concentrated in the South as they were, held captive by the virtual slavery of sharecropping and debt peonage and isolated from the rest of the country in the era before airlines and interstates, many African-Americans had no ready means of making a go of it in what were then faraway alien lands.

By the opening of the 20th century, the optimism of the Reconstruction era had long turned into the terror of Jim Crow. In 1902, one black woman in Alabama seemed to speak for the agitated hearts that would ultimately propel the coming migration: “In our homes, in our churches, wherever two or three are gathered together,” she said, “there is a discussion of what is best to do. Must we remain in the South or go elsewhere? Where can we go to feel that security which other people feel? Is it best to go in great numbers or only in several families? These and many other things are discussed over and over.”

The door of escape opened during World War I, when slowing immigration from Europe created a labor shortage in the North. To fill the assembly lines, companies began recruiting black Southerners to work the steel mills, railroads and factories. Resistance in the South to the loss of its cheap black labor meant that recruiters often had to act in secret or face fines and imprisonment. In Macon, Georgia, for example, a recruiter’s license required a $25,000 fee plus the unlikely recommendations of 25 local businessmen, ten ministers and ten manufacturers. But word soon spread among black Southerners that the North had opened up, and people began devising ways to get out on their own.

As migrants filled Northern factories, groups offering social services handed out advertising cards. (University of Illinois at Chicago, The University Library, Special Collections Department, Arthur and Graham Aldis Papers)

Southern authorities then tried to keep African-Americans from leaving by arresting them at the railroad platforms on grounds of “vagrancy” or tearing up their tickets in scenes that presaged tragically thwarted escapes from behind the Iron Curtain during the Cold War. And still they left.

On one of the early trains out of the South was a sharecropper named Mallie Robinson, whose husband had left her to care for their young family under the rule of a harsh plantation owner in Cairo, Georgia. In 1920, she gathered up her five children, including a baby still in diapers, and, with her sister and brother-in-law and their children and three friends, boarded a Jim Crow train, and another, and another, and didn’t get off until they reached California.

They settled in Pasadena. When the family moved into an all-white neighborhood, a cross was burned on their front lawn. But here Mallie’s children would go to integrated schools for the full year instead of segregated classrooms in between laborious hours chopping and picking cotton. The youngest, the one she had carried in her arms on the train out of Georgia, was named Jackie, who would go on to earn four letters in athletics in a single year at UCLA. Later, in 1947, he became the first African-American to play Major League Baseball.

Had Mallie not persevered in the face of hostility, raising a family of six alone in the new world she had traveled to, we might not have ever known his name. “My mother never lost her composure,” Jackie Robinson once recalled. “As I grew older, I often thought about the courage it took for my mother to break away from the South.”

Mallie was extraordinary in another way. Most people, when they left the South, followed three main tributaries: the first was up the East Coast from Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas and Virginia to Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York and Boston; the second, up the country’s central spine, from Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee and Arkansas to St. Louis, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit and the entire Midwest; the third, from Louisiana and Texas to California and the Western states. But Mallie took one of the farthest routes in the continental U.S. to get to freedom, a westward journey of more than 2,200 miles.

Zora Neale Hurston arrived in the North along the East Coast stream from Florida, although, as was her way, she broke convention in how she got there. She had grown up as the willful younger daughter of an exacting preacher and his long-suffering wife in the all-black town of Eatonville. After her mother died, when she was 13, Hurston bounced between siblings and neighbors until she was hired as a maid with a traveling theater troupe that got her north, dropping her off in Baltimore in 1917. From there, she made her way to Howard University in Washington, where she got her first story published in the literary magazine Stylus while working odd jobs as a waitress, maid and manicurist.

She continued on to New York in 1925 with $1.50 to her name. She would become the first black student known to graduate from Barnard College. There, she majored in English and studied anthropology, but was barred from living in the dormitories. She never complained. In her landmark 1928 essay “How It Feels to Be Colored Me,” she mocked the absurdity: “Sometimes, I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me angry,” she wrote. “It merely astonishes me. How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company? It’s beyond me.”

She arrived in New York when the Harlem Renaissance, an artistic and cultural flowering in the early years of the Great Migration, was in full bloom. The influx to the New York region would extend well beyond the Harlem Renaissance and draw the parents or grandparents of, among so many others, Denzel Washington (Virginia and Georgia), Ella Fitzgerald (Newport News, Virginia), the artist Romare Bearden (Charlotte, North Carolina), Whitney Houston (Blakeley, Georgia), the rapper Tupac Shakur (Lumberton, North Carolina), Sarah Vaughan (Virginia) and Althea Gibson (Clarendon County, South Carolina), the tennis champion who, in 1957, became the first black player to win at Wimbledon.

From Aiken, South Carolina, and Bladenboro, North Carolina, the migration drew the parents of Diahann Carroll, who would become the first black woman to win a Tony Award for best actress and, in 1968, to star in her own television show in a role other than a domestic. It was in New York that the mother of Jacob Lawrence settled after a winding journey from Virginia to Atlantic City to Philadelphia and then on to Harlem. Once there, to keep teenage Jacob safe from the streets, she enrolled her eldest son in an after-school arts program that would set the course of his life.

The trains that spirited the people away, and set the course for those who would come by bus or car or foot, acquired names and legends of their own. Perhaps the most celebrated were those that rumbled along the Illinois Central Railroad, for which Abraham Lincoln had worked as a lawyer before his election to the White House, and from which Pullman porters distributed copies of the Chicago Defender in secret to black Southerners hungry for information about the North. The Illinois Central was the main route for those fleeing Mississippi for Chicago, people like Muddy Waters, the blues legend who made the journey in 1943 and whose music helped define the genre and pave the way for rock ’n’ roll, and Richard Wright, a sharecropper’s son from Natchez, Mississippi, who got on a train in 1927 at the age of 19 to feel what he called “the warmth of other suns.”

In Chicago, Wright worked washing dishes and sweeping streets before landing a job at the post office and pursuing his dream as a writer. He began to visit the library: a right and pleasure that would have been unthinkable in his home state of Mississippi. In 1940, having made it to New York, he published Native Son to national acclaim, and, through this and other works, became a kind of poet laureate of the Great Migration. He seemed never to have forgotten the heartbreak of leaving his homeland and the courage he mustered to step into the unknown. “We look up at the high Southern sky,” Wright wrote in 12 Million Black Voices. “We scan the kind, black faces we have looked upon since we first saw the light of day, and, though pain is in our hearts, we are leaving.”

Richard Wright relocated several times in his quest for other suns, fleeing Mississippi for Memphis and Memphis for Chicago and Chicago for New York, where, living in Greenwich Village, barbers refused to serve him and some restaurants refused to seat him. In 1946, near the height of the Great Migration, he came to the disheartening recognition that, wherever he went, he faced hostility. So he went to France. Similarly, African-Americans today must navigate the social fault lines exposed by the Great Migration and the country’s reactions to it: white flight, police brutality, systemic ills flowing from government policy restricting fair access to safe housing and good schools. In recent years, the North, which never had to confront its own injustices, has moved toward a crisis that seems to have reached a boiling point in our current day: a catalog of videotaped assaults and killings of unarmed black people, from Rodney King in Los Angeles in 1991, Eric Garner in New York in 2014, Philando Castile outside St. Paul, Minnesota, this summer, and beyond.

Thus the eternal question is: Where can African-Americans go? It is the same question their ancestors asked and answered, only to discover upon arriving that the racial caste system was not Southern but American.