Happy Friday POU! This week we have highlighted the relationship between the African-American and Jewish communities throughout different periods of time. Today, we will continue to highlight relations through the Civil Rights and Labor movements.

Black power movement

From 1966, the collaboration between Jews and blacks unraveled. Jews were increasingly transitioning to middle-class and upper-class status, creating a gap in relations between Jews and blacks. Many black leaders, including some from the Black Power movement, became outspoken in their demands for greater equality, often criticizing Jews along with other white targets.

In 1966, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) voted to exclude whites from its leadership, a decision that resulted in the expulsion of several Jewish leaders.

In 1967, black academic Harold Cruse attacked Jewish activism in his 1967 volume The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual in which he argued that Jews had become a problem for blacks precisely because they had so identified with the Black struggle. Cruse insisted that Jewish involvement in interracial politics impeded the emergence of “Afro-American ethnic consciousness”. For Cruse, and for other black activists, the role of American Jews as political mediators between Blacks and whites was “fraught with serious dangers to all concerned” and must be “terminated by Negroes themselves.”

Black Hebrew Israelites

Black Hebrew Israelites are groups of people, mostly of Black American ancestry, situated mainly in the Americas who claim to be descendants of the ancient Israelites. To varying degrees, Black Hebrews adhere to the religious beliefs and practices of both mainstream Judaism and Christianity, though they mostly get their doctrines from Christian resources. They are generally not accepted as Jews by Orthodox or Conservative Jews, nor are they accepted by the greater Jewish community, because of their divergence from mainstream Judaism, and their frequent hostility to Jews.

Many Black Hebrews consider themselves—and not Jews—to be the only authentic descendants of the ancient Israelites. Some groups identify themselves as Hebrew Israelites, other groups identify themselves as Black Hebrews, and other groups identify themselves as Jews. Dozens of Black Hebrew groups were founded in the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Labor movement

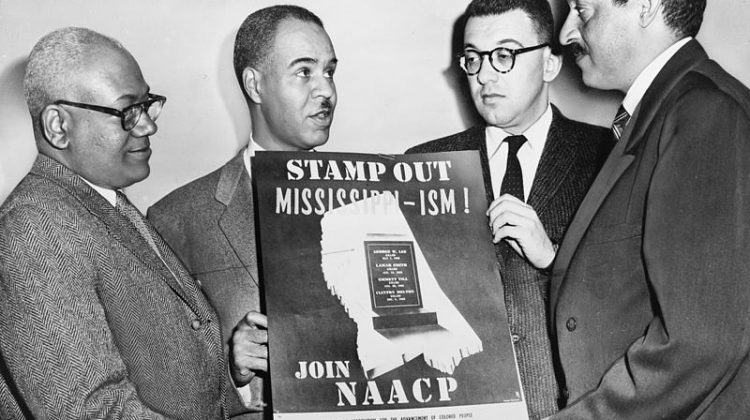

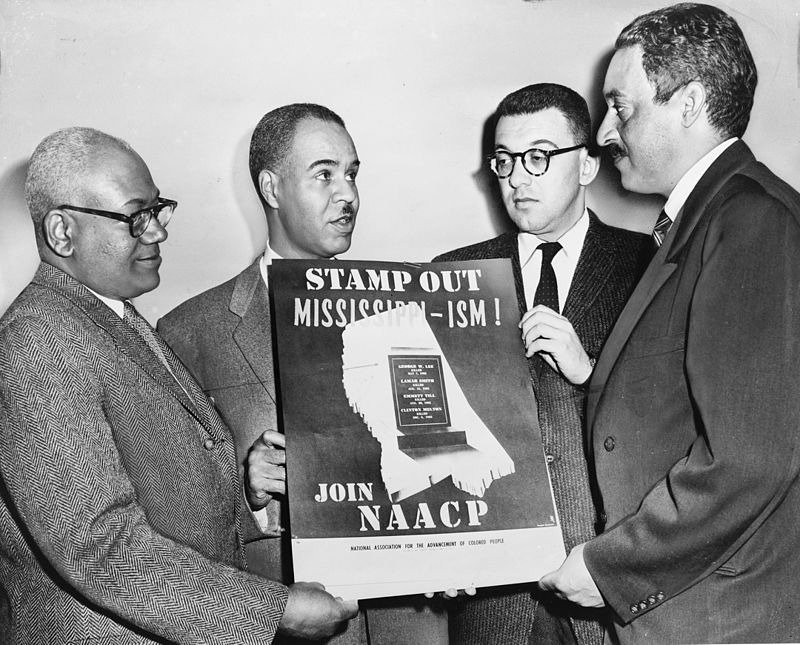

Herbert Hill (second from right), labor director of NAACP, with Thurgood Marshall (second from left)

The labor movement was another area of the relationship that flourished before WWII but ended in conflict afterward. In the early 20th century, one important area of cooperation was attempts to increase minority representation in the leadership of the United Automobile Workers (UAW). In 1943, Jews and blacks joined to request the creation of a new department within the UAW dedicated UAW leaders refused to minorities, but that request.

In the immediate post-World War II period, the Jewish Labor Committee (JLC), which was founded in February 1934 to oppose the rise of Nazism in Germany, formed approximately two dozen local committees to combat racial intolerance in the U. S and Canada. The JLC, which had local offices in several communities in North America, helped found the United Farm Workers and campaigned for passaging California’s Fair Employment Practices Act, and provided staffing and support for the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom led by Martin Luther King Jr, A. Philip Randolph, and Bayard Rustin.

Beginning in early 1962, NAACP labor director Herbert Hill made allegations that since the 1940s, the JLC had also defended the anti-black discriminatory practices of unions in both the garment and building industries. Hill claimed that the JLC changed “a black, white conflict into a Black-Jewish conflict”. He said the JLC defended the Jewish leaders of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) against charges of anti-black racial discrimination, distorted government reports about discrimination, failed to tell union members the truth, and when union members complained, the JLC labeled them antisemites. ILGWU leaders denounced Black members for demanding equal treatment and access to leadership positions.

The New York City teachers’ strike of 1968 also signaled the decline of black-Jewish relations: the Jewish president of the United Federation of Teachers, Albert Shanker, made statements that were seen by some as straining black-Jewish relations by accusing black teachers of antisemitism.