Imagine former slaves organizing a convention after the Civil War, with delegates from former confederate states. Each traveling to New Orleans, to convene and discuss their futures. No telephones, no telegraphs…NO MONEY. But a will to survive and live their lives.

Historial Nell Irvin Painter talks about “The Colonization Council” in her book on The Exodusters.

Kansas Vs. Liberia

Before the Exodus of 1879 to Kansas, southern blacks convened to discuss the option of emigration both formally and informally. Delegates from Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Texas, Arkansas, and Georgia met at a New Orleans conference in 1875 and discussed black emigration to western territories and Liberia. Black settlement outside of the South as a result of emigration was termed “colonization,” and the New Orleans committee meeting became a full-fledged organization dubbed, “The Colonization Council.” The Council held its first public meetings in 1877. Council meetings consisted of speechmaking and petition writing and signing, with some 98,000 men, women, and children from Louisiana signed onto emigration lists.

Liberia proved an unrealistic destination for Black refugees financially and logistically. As the land of John Brown, Kansas had fought bitterly for its Free State status, and took its fair treatment of black immigrants as a point of pride. Kansas did not actively encourage the Exodusters; rather, its equal opportunity stance was more welcoming in comparison to most of the country.

Very little is written at all about this historic meeting. One of the organizers was former slave Henry Adams.

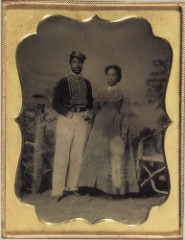

Henry and Malinda Adams

Henry Adams was a Louisiana leader who advocated the emigration of southern freed blacks to Liberia after emancipation. Born a slave in Newton County, Georgia on March 16, 1843, Henry Adams was originally born as Henry Houston but changed his name at the age of seven. His enslaved family was relocated to Louisiana in 1850 and lived there until 1861.

Adams married a woman named Malinda during his enslavement and the couple had four children. Unlike most enslaved people, Adams and his wife were able to acquire property during the Civil War.

After the war Adams moved to DeSoto Parish in Louisiana where he started a successful peddling business. Adams eventually became a merchant but in 1866 at the age of 23 he enlisted in the U.S. Army. Adams was discharged in September 1869 after rising to the rank of quartermaster sergeant. Adams learned to read and write in the Army, providing him a measure of self-confidence that encouraged his leadership of other ex-slaves once he returned to civilian life.

In 1870 Adams organized black Louisiana veterans in the Shreveport area into a group known as “the Committee.” Numbering about 500 men — including 150 who traveled across northwest Louisiana working with Republican politicians and encouraged black men to vote — the Committee worked for full political rights for African Americans. Adams lost jobs because of his involvment with the organization but he continued to press for political reforms.

In the summer of 1874, the Louisiana Governor William Pitt Kellogg, a Republican, and the Committee made a request for federal troops to intervene in areas of northwest Louisiana where the White League, a terrorist organization, had taken control. President Ulysses S. Grant responded by sending the U.S. Seventh Cavalry to Shreveport. While the Seventh Cavalry operated in Shreveport, Adams gained employment as an undercover scout in 1875.

During this period Adams also traveled to New Orleans to meet with black delegates who advocated emigration from the United States to Liberia. These leaders, who called themselves the Colonization Council, were convinced that African Americans would never have full citizenship rights. Persuaded by their ideas, Adams joined the organization.

The end of Reconstruction in Louisiana, following the Presidential Election compromise of 1876, brought the Democrats back into power in the state. It also presented the Colonization Council with a new political environment that made their goals more attractive to Louisiana blacks.

In 1877, during one of the Council’s meetings, Adams made his first public speech advocating the emigration of African Americans from the South. The Colonization Council then drew up a petition and circulated it at their subsequent meetings. According to Adams, over 98,000 men, women, and children signed the petitions. In September 1877, Adams sent the petition to President Hayes, but was denied federal funds to help the migration. Support for the movement began to wane as members of the Colonization Council lost interest, fell into deeper poverty, and returned to their farming jobs.

In the Spring of 1879 the Kansas Exodus swept across Louisiana and Mississippi. Adams quickly shifted the focus of the Colonization Council to Kansas and encouraged blacks to migrate there. Adams never visted Kansas. However, in 1880 he traveled to Washington, D.C. to give testimony before a U.S. Senate Committee on the migration and continuing emigration sentiment, both of which he blamed on anti-black terror in the South.

Henry Adams dropped out of sight in 1884. The efforts of Adams and the Colonization Council were not unrewarded. Over the next three decades, more than 11,000 southern blacks settled in Liberia. It is unclear if Henry Adams was among them.

“Testimony of Henry Adams regarding the Negro Exodus.” From Herbert Aptheker, editor, A Documentary History of the Negro People in the United States (New York, 1951), p. 715.

In the spring of 1879, thousands of colored people, unable longer to endure the intolerable hardships, injustice, and suffering inflicted upon them by a class of Democrats in the South, had, in utter despair, fled panic-stricken from their homes and sought protection among strangers in a strange land. Homeless, penniless, and in rags, these poor people were thronging the wharves of Saint Louis, crowding the steamers on the Mississippi River, and in pitiable destitution throwing themselves upon the charity of Kansas. Thousands more were congregating along the banks of the Mississippi River, hailing the passing steamers, and imploring them for a passage to the land of freedom, where the rights of citizens are respected and honest toil rewarded by honest compensation. The newspapers were filled with accounts of their destitution, and the very air was burdened with the cry of distress from a class of American citizens flying from persecutions which they could no longer endure.1

This quotation is from the minority report of an 1880 Senate committee appointed to investigate the causes of a mass black migration from the South during the 1870s. For African Americans, the “redemption” of the South by former Confederates after the 1876 presidential election resulted in political disfranchisement, economic repression, and relentless terror. The joyful exuberance and hope evident among the “freedmen” at the end of the Civil War—and during the heady days of Reconstruction and African American political participation—had been dashed. Many black southerners sought to escape this predicament by leaving the region and migrating to states in the North and Midwest. Chief among these destinations was Kansas. Henry Adams testified before the US Senate on behalf of the former slaves. This is his recorded testimony.

Question:

Now tell us, Mr. Adams, what, if anything, you know about the exodus of the colored people from the Southern to the Northern and Western States; and be good enough to tell us in the first place what you know about the organization of any committee or society among the colored people themselves for the purpose of bettering their condition, and why it was organized. Just give us a history of that as you understand it.

Henry Adams:

Well, in 1870, I believe it was, or about that year, after I had left the Army—I went into the Army in 1866 and came out the last of 1869—and went right back home again where I went from, Shreveport; I enlisted there, and went back there. I enlisted in the Regular Army, and then I went back after I came out of the Army. After we had come out a parcel of we men that was in the Army and other men thought that the way our people had been treated during the time we was in service—we heard so much talk of how they had been treated and opposed so much and there was no help for it—that caused me to go into the Army at first, the way our people was opposed. There was so much going on that I went off and left it; when I came back it was still going on, part of it, not quite so bad as at first. So a parcel of us got together and said that we would organize ourselves into a committee and look into affairs and see the true condition of our race, to see whether it was possible we could stay under a people who had held us under bondage or not. Then we did so and organized a committee.

Question:

What did you call your committee?

Henry Adams:

We just called it a committee, that is all we called it, and it remained so; it increased to a large extent, and remained so. Some of the members of the committee was ordered by the committee to go into every State in the South where we had been slaves there, and post one another from time to time about the true condition of our race, and nothing but the truth.

Question:

You mean some members of your committee?

Henry Adams:

That committee; yes, sir.

Question:

They traveled over the other States?

Henry Adams:

Yes, sir; and we worked some of us, worked our way from place to place and went from State to State and worked—some of them did—amongst our people in the fields, everywhere, to see what sort of living our people lived; whether we could remain in the South amongst the people who had held us as slaves or not. We continued that on till 1874.

Question:

Now, before you come to 1874, let me ask you how extensive was the operation of your committee? Did they go into almost all the Southern States?

Henry Adams:

Nearly all of the States we could get reports from as to how our race was living there.

Question:

Whom did you report to?

Henry Adams:

To the committee; we reported to the Committee there.

Question:

To the committee at Shreveport?

Henry Adams:

Yes. The reports were sent, and our committee met, so that they would be read at the meeting.

Question:

Were they addressed to the committee or to some individual?

Henry Adams:

They were addressed to some individual of the committee—just addressed to the members or ones that we knowed belonged to the committee, and knowed would get the letters we would write to them.

Question:

Was the object of that committee at that time to remove your people from the South, or what was it?

Henry Adams:

O, no, sir; not then; we just wanted to see whether there was any State in the South where we could get a living and enjoy our rights.

Question:

The object, then, was to find out the best places in the South where you, could live?

Henry Adams:

Yes, sir; where we could live and get along well there and tow investigate our affairs—not to go nowhere till we saw whether we could stand it.

Question:

How were the expenses of these men paid?

Henry Adams:

Every one paid his own expenses, except the one we sent to Louisiana and Mississippi. We took money out of our pockets and sent him, and said to him you must now go to work. You can’t find out anything till you get amongst them. You can talk as. much as you please, but you have got to go right into the field and work with them and sleep with them to know all about them.

Question:

Have you any idea how many of your people went out in that way?

Henry Adams:

At one time there was five hundred of us.

Question:

Do you mean five hundred belonging to your committee?

Henry Adams:

Yes, sir.

Question:

I want to know how many traveled in that way to get at the condition of your people in the Southern States?

Henry Adams:

I think about one hundred or one hundred and fifty went from one place or another.

Question:

And they went from one place to another, working their way and paying their expenses and reporting to the common center at Shreveport, do you mean?

Henry Adams:

Yes, sir.

Question:

What was the character of the information that they gave you?

Henry Adams:

Well, the character of the information they brought to us was very bad, sir.

Question:

In what respect?

Henry Adams:

They said that in other parts of the country where they traveled through, and what they saw they was comparing with what we saw and what we had seen in the part where we lived; we knowed what that was; and they cited several things that they saw in their travels; it was very bad.

Question:

Do you remember any of these reports that you get from members of your committee?

Henry Adams:

Yes, sir; they said in several parts where they was that the land rent was still higher there in that part of the country than it was where we first organized it, and the people was still being whipped, some of them, by the old owners, the men that had owned them as slaves, and some of them was being cheated out of their crops just the same as they was there.

Question:

Was anything said about their personal and political rights in these reports, as to how they were treated about these?

Henry Adams:

Yes, some of them stated that in some parts of the country where they voted they would be shot. Some of them stated that if they voted the Democratic ticket they would not be injured.

Question:

But that they would be shot, or might be shot, if they voted the Republican ticket?

Henry Adams:

Yes, sir.

Question:

State what was the general character of these reports—I have not yet got down to your organization of 1874—whether what you have given was the general character; were there some safer places found that seemed a little better?

Henry Adams:

Some of the places, of course, were a little better than others. Some men that owned some of the plantations would treat the people pretty well in some parts. We found that they would try to pay what they had promised from time to time; some they didn’t pay near what they had promised; and in some places the families—some families—would make from five to a hundred bales of cotton to the family; then at the end of the year they would pay the owner of the land out of that amount at the end of the year, maybe one hundred dollars. Cotton was selling then at twenty-five cents a pound, and at the end of the year when they came to settle up with the owner of the land, they would not get a dollar sometimes, and sometimes they would get thirty dollars, and sometimes a hundred dollars out of a hundred bales of cotton.

Question:

What were the best localities that you heard from, if you remember, where they were treated the best?

Henry Adams:

In Virginia was what they stated was the State that treated them best in the South; Virginia and Missouri, and Kentucky, and Tennessee.

Question:

There the treatment was better was it?

Henry Adams:

Yes, sir; it was better there.

Question:

Had you any reports from North Carolina?

Henry Adams:

Some few from North Carolina.

Question:

Do you remember anything about them; or is your knowledge of that State only general?

Henry Adams:

Well, they reported that some parts of North Carolina was very bad and other parts was very good….

Question:

I am speaking now of the period from 1870 to 1874, and you have given us the general character of the reports that you got from the South; what did you do in 1874?

Henry Adams:

Well, along in August sometime in 1874, after the white league sprung up, they organized and said this is a white man’s government, and the colored men should not hold any offices; they were no good but to work in the fields and take what they would give them and vote the Democratic ticket. That’s what they would make public speeches and say to us, and we would hear them. We then organized an organization called the colonization council.

Question:

What was the difference between that organization and your committee, as to its objects?

Henry Adams:

Well, the committee was to investigate the condition of our race.

Question:

And this organization was then to better your condition after you had found out what that condition was?

Henry Adams:

Yes, sir.

Question:

The result of this investigation during these four years by your committee was the organization of this colonization council. Is that the way you wish, me to understand it?

Henry Adams:

It caused it to be organized.

Question:

It caused it to be organized. Now, what was the purpose of this colonization council?

Henry Adams:

Well, it was to better our condition.

Question:

In what way did you propose to do it?

Henry Adams:

We first organized and adopted a plan to appeal to the President of the United States and to Congress to help us out of our distress, or protect us in our rights and privileges.

Question:

Well, what other plan had you?

Henry Adams:

And if that failed our idea was then to, ask them to set apart a territory in the United States for us, somewhere, where we could go and live with our families.

Question:

You preferred to go off somewhere by yourselves?

Henry Adams:

Yes.

Question:

Well, what then?

Henry Adams:

If that failed, our other object was to ask for an appropriation of money to ship us all to Liberia, in Africa; somewhere where we could live in peace and quiet.

Question:

Well, and what after that?

Henry Adams:

When that failed then our idea was to appeal to other governments outside of the United States to help us to get away from the United States and go there and live under their flag.

Question:

Well, what did your council do now under these various modes of relief which they had marked out for themselves?

Henry Adams:

Well, we appealed, as we promised.

Question:

Did you make any appeal to Congress and to the President?

Henry Adams:

Yes, sir.

Question:

Who, in your association, authorized that appeal; how was it gotten up?

Henry Adams:

It was gotten up by resolution.

Question:

By resolution?

Henry Adams:

Yes, sir; and just passed by the organization.

Question:

Well, by “the organization,” what do you mean?

Henry Adams:

I mean the members. of it.

Question:

Did they have meetings?

Henry Adams:

Yes, sir.

Question:

How were these meetings held and where did they hold them?

Henry Adams:

We held them in rooms and houses.

Question:

Were they secret meetings or public?

Henry Adams:

We didn’t allow nobody in there but our friends. If he was not a member he couldn’t get in until we came out in public. When we called a public meeting we came out to the park or anywhere, and didn’t care who heard. Then anybody could participate who believed in our movement.

Question:

Now, let us understand, before we go any further, the kind of people who composed that association. The committee, as I understand you, was composed entirely of laboring people?

Henry Adams:

Yes, sir.

Question:

Did it include any politicians of either color, white or black?

Henry Adams:

No politicianers didn’t belong to it, because we didn’t allow them to know nothing about it … we didn’t trust any of them …

Question:

Now, when you organized the council what kind of people were taken into it?

Henry Adams:

Nobody but laboring men … When we met in committee there was not any of us allowed to tell our name … We first appealed to President Grant … That was in September, 1874 … at other times we sent to Congress … We told them our condition, and asked Congress to help us out of our distress and protect us in our lives and property, and pass some law or provide some way that we might get our rights in the South, and so forth … After the appeal in 1874, we appealed when the time got so hot down there they stopped our churches from having meetings after nine o’clock at night. They stopped them from sitting up and singing over the dead, and so forth, right in the little town where we lived, in Shreveport. I know that to be a fact; and after they did all this, and we saw it was getting so warm—killing our people all over the whole country—there was several of them killed right down in our parish—we appealed … We had much rather staid there [South] if we could have had our rights … In 1877 we lost all hopes … we found ourselves in such condition that we looked around and we seed that there was no way on earth, it seemed, that we could better our condition there, and we discussed that thoroughly in our organization along in May. We said that the whole South—every State in the South—had got into the hands of the very men that held us slaves—from one thing to another and we thought that the men that held us slaves was holding the reins of government over our heads in every respect almost, even the constable up to the governor. We felt we had almost as well be slaves under these men. In regard to the whole matter that was discussed, it came up in every council. Then we said there was no hope for us and we had better go … Then, in 1877 we appealed to President Hayes and to Congress, to both Houses. I am certain we sent papers there; if they didn’t get them that is not our fault; we sent them … . Mighty few ministers would allow us to have their churches [for meetings]; some few would in some of the parishes … When we held our meetings we would not allow the politicians to speak … . it is not exactly five hundred men belonging to the council … they have now got at this time 98,000 names enrolled … men and women, and none under twelve years .old … some in Louisiana—the majority of them in Louisiana, and some in Texas, and some in Arkansas … a few in Mississippi … a few in Alabama [and] in a great many of the others …

Question:

Now, Mr. Adams, you know, probably, more about the causes of the exodus from that country than any other man, from your connection with it; tell us in a few words what you believe to be the causes of these people going away?

Henry Adams:

Well, the cause is, in my judgment, and from what information I have received, and what I have seen with my own eyes—it is because the largest majority of the people, of the white people, that held us as slaves treats our people so bad in many respects that it is impossible for them to stand it. Now, in a great many parts of that country there our people most as well be slaves as to be free; because, in the first place, I will state this: that in some times, in times of politics, if they have any idea that the Republicans will carry a parish or ward, or something of that kind, why, they would do anything on God’s earth. There ain’t nothing too mean for them to do to prevent it; nothing I can make mention of is too mean for them to do … .

Senate Report 693, 46th Cong., 2nd Sess., part 2, pp. 101-111.