Happy Friday POU!

Destination Freedom premiered on June 27, 1948 on Chicago radio WMAQ and consisted of 91 different scripts produced solely by Richard Durham. Destination Freedom was a provocative half-hour show that showcased the lives and accomplishments of prominent African Americans. Destination Freedom demonstrated personalities that were in the words of the author “rebellious, biting, scornful, angry and cocky.” Durham once told an interviewer that the goal of his program was to cut through the false images of black life propagated through the popular arts.

As they have related historically to black Americans, the popular arts in the United States have been marked by two discernible patterns of behavior: heavy reliance on negative racial stereotypes and chronic discrimination against participation by African Americans. In the various media—literature, motion pictures, music, radio, television—racist impediments against equitable black depiction and involvement led to gross physical distortions, persistent typologies that one media historian summarized as “toms, coons, mulattoes, mammies, and bucks,”‘ as well as gross underrepresentation of blacks in the creative and business aspects of the mass-culture industry.

This was the pop culture of a society tolerant of racial discrimination, a society that found in such imagery a justification for public and private manifestations of racism. This was also entertainment for profit, produced by an arts business that systematically barred blacks from participation, except within the bounds of those restrictive and demeaning stereotypes.

Of all the media, however, the pattern of derision and exclusion was most keenly felt in network radio during its so-called Golden Age from the early 1930s to the early 1950s. Where there were viable if small minority-oriented literary forums, musical productions, and motion picture companies, radio was dominated by three or four national broadcasting networks. Although television has been controlled largely by those same networks, TV has been more temperate because it matured and flourished in an era of profound challenges to traditional racist attitudes. There were no similar circumstances militating against the abuse of African Americans in network radio.

Certainly, there were black radio performers like Eddie Anderson, Lillian and Amanda Randolph, Eddie Green, Hattie McDaniel, Ruby Dandridge, and Juano Hernandez, but their roles were either stereotypically comedic or insubstantial. And there were so many areas where African Americans never participated: No black men or women reported the news; there were no black sportscasters, no black soap operas; and no substantial black roles appeared in romances or dramas or Westerns or detective shows. Further, there were no black network executives, producers, directors, or writers. Radio was a lily-white medium, an industry that in its years of optimal influence did little to alter the racial peculiarities of the United States.

In light of such traditions, the appearance in the late 1940s of the radio series Destination Freedom constitutes a striking incongruity. A local show that for more than two years appeared on WMAQ, the owned-and-operated station of the National Broadcasting Company in Chicago, Destination Freedom was a provocative half-hour Sunday feature that probed with remarkable candor the accomplishments of prominent African Americans. Through dramatic sketches culled from black history, this series maturely illustrated the methods by which black achievers, such as Benjamin Banneker, Sojourner Truth, Booker T. Washington, Marian Anderson, Langston Hughes, and Joe Louis, managed to succeed despite confrontations with systemic racism. In contrast to the roles as maids, cooks, butlers, and buffoons in which radio usually cast blacks, the principals of Destination Freedom demonstrated personalities that were, in the words of the program’s author, “rebellious, biting, scornful, angry, cocky, as the occasion calls for—not forever humble, meek, etc., as some would like to imagine it.”‘

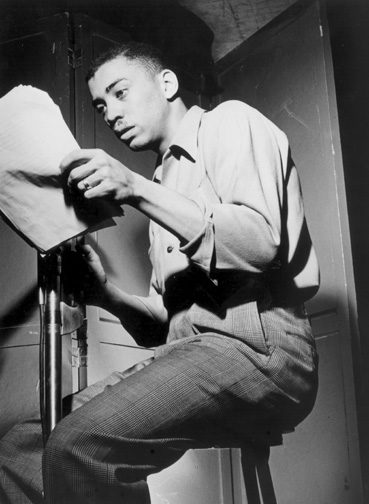

Destination Freedom premiered on June 27, 1948, and until it was altered in format in August 1950, the ninety-one different scripts produced for the program were the product of one man, Richard Durham. He was born September 6, 1917, in Raymond, Mississippi; but he was raised in Chicago. He died April 24, 1984. Durham learned his radio craft during the Depression as a young dramatist with the Writers Project of the WPA. Before undertaking Destination Freedom, he had studied at Northwestern University and had been an editor at the prestigious African American newspaper, the Chicago Defender. His first major radio experience came in Chicago with the quarter-hour series, Democracy U.S.A., which he wrote from 1946 to 1948 for the local CBS station, WBBM. In that period he also wrote the radio series Here Comes Tomorrow, a black soap opera which was produced only in Chicago for station WJJD.

In Destination Freedom, Durham’s writing skills and social philosophy blossomed. Complemented by young minority actors like Oscar Brown, Jr., Janice Kingslow, Wezlyn Tilden, and Fred Pinkard, he brought to the program a sense of crusade. According to him, “at that time you were running with the wind in your face [so] there was that thing of a crusading spirit—of a drive to get the story over.” More explicitly, Durham told an interviewer at the time that the goal of his program was to cut through the false images of black life propagated through the popular arts. With Destination Freedom he hoped to expose “the camouflage of crackpots and hypocrites—false liberals and false leaders—of radio’s Beulahs and Amos and Andy’s, and Hollywood Stepin Fetchit’s and its masturbation with self-flattering dreams of passing for white such as Pinky and Imitation of Life.”

The success of Destination Freedom was underscored in several ways. Although Durham was paid only $125 per script and the series was without an underwriter for most of its tenure on WMAQ—the Chicago Defender paid part of its costs for the first thirteen weeks, and in early 1950 the Urban League of’ Chicago helped to sponsor several broadcasts—Destination Freedom was recognized for its singular contribution to public education and the enhancement of race relations. In 1949 it was cited by the South Central Association of Chicago as “one of the finest programs of its kind” and as “a splendid contribution…toward the achievement of democracy in our time.” The same year the series awarded a first-place commendation by the prestigious Institute for Education by Radio at Ohio State University for its “vital, compelling use of radio technique in presenting contributions of Negroes to the development of democratic traditions and the American way of life.”

Appropriately, on the first anniversary broadcast of Destination Freedom, Governor Adlai Stevenson appeared by transcription to laud the series for its promotion of “understanding an tolerance among the American people” and for doing so much “to familiarize us with the many contributions which Negroes have made to American life.”‘

Reading the scripts forty years after they were written, the perceptive and powerful import ofDestination Freedom remains apparent. A decade before the appearance of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the black social movement he energized, Richard Durham’s program enunciated

the social and political goals of the civil rights movement. All of Durham’s central characters were achievers. Heroes like Crispus Attucks, confident in the validity of their inner convictions, preferred to confront bigotry and live or perish by their values. Others like Henry Armstrong were forced by adversity to adapt, turning to an outstanding career in boxing when racist barriers prevented him from enrolling in a medical college in St. Louis. In the case of business executive William Nickerson, Jr., prejudice in the insurance industry led directly to his creation of the successful Golden State Life Insurance Company.

Despite their victories over discrimination, Durham’s principals were never able to forget the fragile nature of their triumphs. Whether it was singer-actress Lena Horne being refused service in a southern restaurant, or world-renowned Mary Church Terrell being ejected from a public bus in Washington, D.C., because she would not sit in the rear, Durham poignantly illustrated that all blacks must be prepared to encounter racist challenges at any point in their lives.

In preparing the scripts for Destination Freedom, Durham worked usually in historical materials—monographs, encyclopedias, biographies, and autobiographies. Oscar Brown, Jr., recalled the long hours Durham spent in the local public library piecing together fragmented historical accounts to produce a final script. Black history was not widely researched in the late 1940s, yet Durham’s vigorous fascination with the subject is obvious. Ranging from Aesop, the Ethiopian bard of fable to contemporary leaders of African American society, his heroes were strong actors who influenced their times. Writing in 1949 to Homer Heck, the first producer and director of Destination Freedom, Durham summarized his view of black men or women in history, and of their relationship to his radio series.

A good many white people have cushioned themselves into dreaming that Negroes are not self-assertive, confident, and never leave the realm of fear and subservience—to portray them as they are will give a greater education (to the audience) than a dozen lectures…. His role in society and history has been so distorted—so much based on illusion, chauvinism and conjecture—so much a part of the psychological need of a good many whites for some excuse to carry on untenable attitudes—that the first point in the series was to bring up some little known facts of history which would give the audience a new insight on people in general.

Durham was not an academic historian, and Destination Freedom never purported to be historiographical. However, the program offered stories drawn from historical reality but fictionalized in terms of conversation and dramatic pace. Durham was a student of history—particularly that which encompassed the black experience—and his series presented fiction crafted from careful research.

Richard Durham understood that as a radio dramatist he was composing a popularized form of history, sharing the story of blacks with a public for the most part familiar only with the pejorative stereotypes of his race that were propagated through the mass media. His was a cause he felt himself sharing with all those associated with Destination Freedom. In 1949 he explained his challenge: “To break through the stereotype—shatter the conventions and traditions which have prevented us from dramatizing the infinite store of material from the history and current struggles for freedom—is the job cut out for writers, actors and directors working with Negro material.”

In view of the conservative nature of radio programming, the revolutionary message of Destination Freedom was striking. Except for wartime propagandizing, commercial broadcasting was unfamiliar with suggestions of revolt. Certainly, patriotic dramas utilized the utterances of colonial leaders like Thomas Jefferson and Patrick Henry, but it was a major departure to broadcast the fiery appeals, even historical ones, of black radicals—and to declare that as far as people of color were concerned the American revolution remained incomplete.

Needless to say, the series received complaints from the public. Durham recalled civic groups such as the American Legion and the Knights of Columbus protesting specific programs . He encountered resistance from WMAQ—which had to approve all his scripts—when he proposed dramas based on the lives of black leaders, like Nat Turner and Paul Robeson, who were considered too controversial. And editing done at the studio occasionally toned down the anger in Durham’s message. For example, in the script for “Segregation, Incorporated”—a stinging critique of racial segregation in Washington, D.C.—Durham asserted that such practices were promoting a “master race” philosophy in the United States. This allegation was deleted from the actual broadcast.

Nonetheless, references to Nat Turner appeared in several programs, and the bite of Destination Freedom was unmistakable, even with occasional edits. Moreover, the series was sustained by WMAQ until the summer of 1950 when pressures from the new war in Korea and the swelling tide of anticommunism did much to blunt all liberal creativity in the popular arts. At that juncture, Destination Freedom became a patriotic series hosted by “Paul Revere” and featuring dramas of traditional white heroes like Dwight D. Eisenhower, and “average people” whose stories offered lessons in Americanism.

Richard Durham’s social and political concepts were singularly progressive. Although egalitarian ideals were advanced in film and literature in the late 1940s, Destination Freedom was the most consistent and prolonged protest against injustice in all the popular arts. In the two years of the program no one wrote more pointedly or more prolifically on the subject of racial prejudice than Richard Durham.