Happy Friday POU! Today we look at some of the most significant pieces of African art that remains in the hands of European museums as a result of looting and colonization.

The Benin Bronzes

The Benin Bronzes, which are actually made of brass, are a collection of delicately made sculptures and plaques that adorned the royal palace of the Oba, Ovonramwen Nogbaisi, in the Kingdom of Benin, which was incorporated into British-ruled Nigeria.

They were carved out of ivory, brass, ceramic and wood. Many of the pieces were cast for the ancestral altars of past kings and queen mothers.

In 1897, the British launched a punitive expedition against Benin, in response to an attack on a British diplomatic expedition. Apart from bronze sculptures and plaques, innumerable royal objects were taken as a result of the mission and are scattered all over the world.

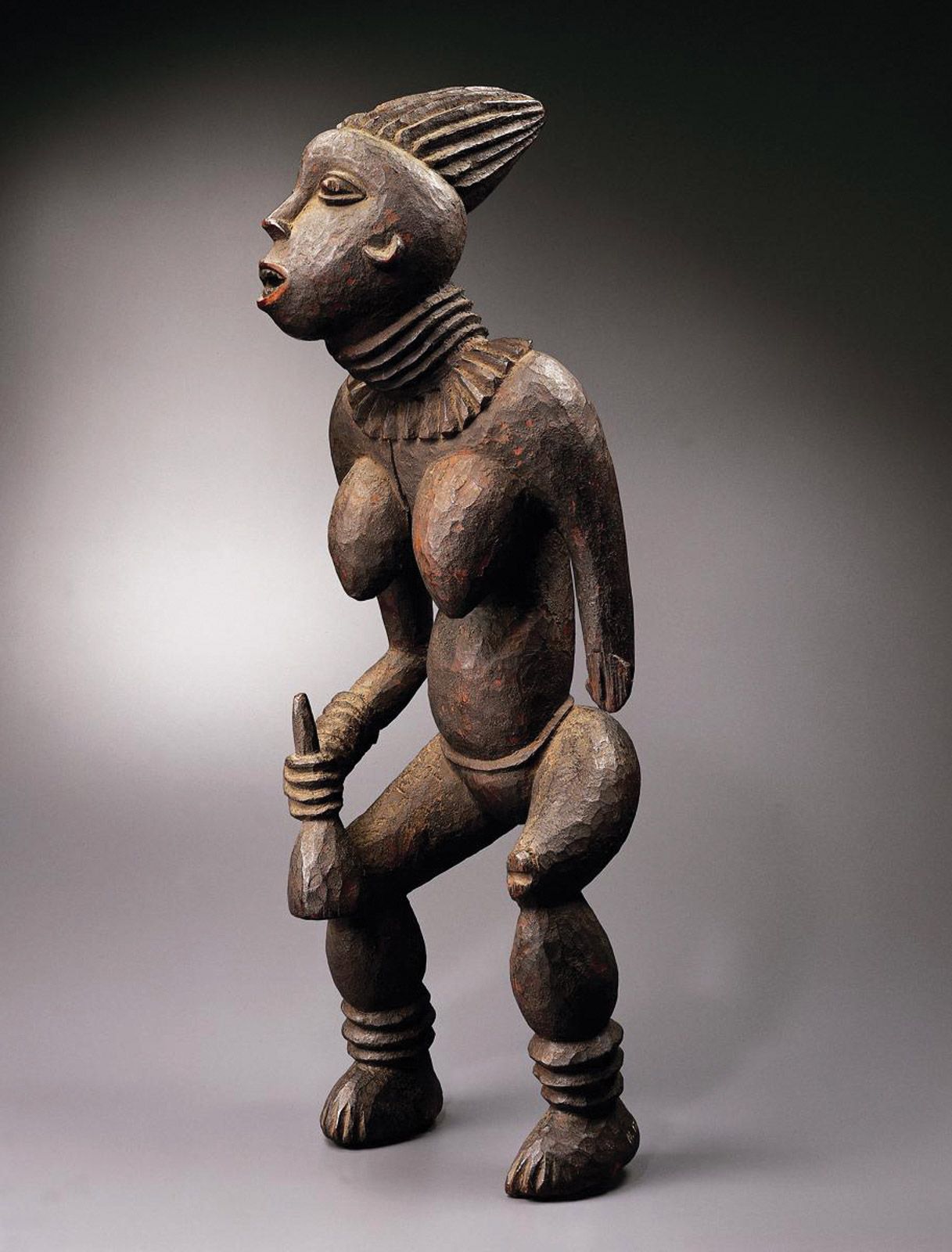

Bangwa Queen

The 32in (81cm) tall Bangwa Queen is a wooden carving from Cameroon, representing the power and health of the Bangwa people.

It is one of the world’s most famous pieces of African art and has huge sacred significance for Cameroonians.

Sculptures were made of titled royal wives or princesses and would be referred to as Bangwa Queens in the Bangwa land of present-day Lebialem district of Cameroon’s South-West region.

The Bangwa Queen was either given to or looted by the German colonial agent Gustav Conrau in around 1899 before the territory was colonised.

It ended up in the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin and was then bought by an art collector in 1926.

According to the New York Times, US art collector Harry A Franklin bought the carving in 1966 for $29,000 and after his death it sold at a Sotheby’s auction for $3.4m.

Surrealist portrait photographer Man Ray also included the Queen of Bangwa in a 1937 portrait of a nude model – in what the New York Times says became one of his famous images.

The Dapper Foundation in Paris, France now owns the Bangwa Queen sculpture – and it was on display at the Musée Dapper until 2017 when the museum that focused on African art closed because of low attendance and high maintenance costs.

Traditional leaders of the Bangwa have been corresponding with the foundation, requesting its return to Cameroon.

Authors of the report commissioned by President Macron, Senegalese writer and economist Felwine Sarr and French Historian Bénédicte Savoy, have recommended that French law is changed to allow the return of the African art.

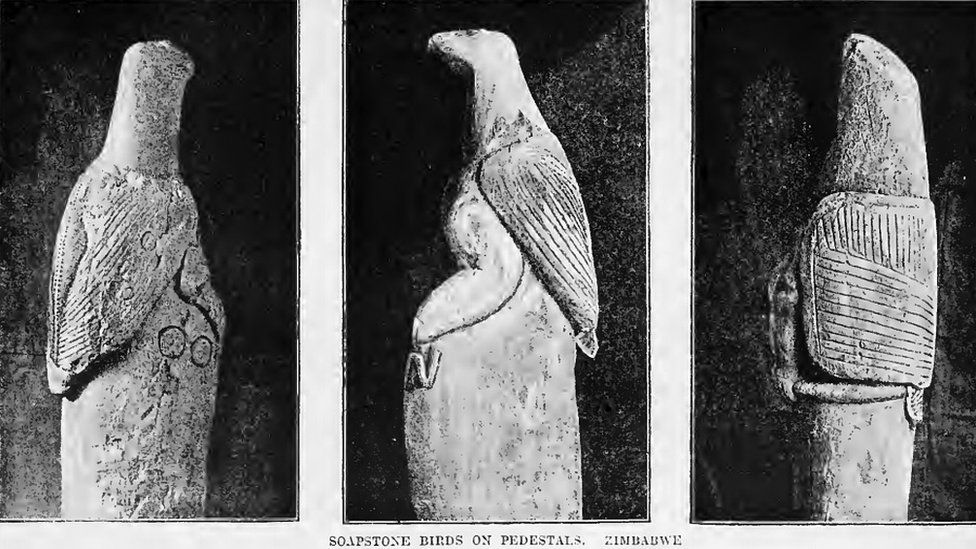

Zimbabwe bird

A soapstone sculpture of a fish eagle is Zimbabwe’s main national emblem. Eight of the Zimbabwe Birds were looted from the ruins of an ancient city.

Only eight of the birds were ever recovered. They stood on the walls and monoliths of the ancient city built between the 12th and 15th Centuries by the ancestors of the Shona people.

Seven of the carvings are in Zimbabwe since 2003 when the bottom section of one was returned by Germany.

It had ended up in the hands of a German missionary who sold it to the Ethnological Museum in Berlin in 1907.

Then after Soviet troops invaded Germany at the end of the World War Two, it was moved from Berlin to Leningrad and remained there to the end of the Cold War and then returned to Germany.

The eighth remains in the old bedroom of 19th Century British imperialist Cecil Rhodes, whose home in the South African city of Cape Town is now a museum.

He had taken a number of birds from Great Zimbabwe to South Africa in 1906. South Africa returned four of them in 1981, a year after Zimbabwe gained its independence.

The Bust of Nefertiti

The bust of Nefertiti was created around 1340 BC by the court sculptor Thutmose, in whose studio in Amarna she stood as a sculptor’s model.

The bust of Nefertiti, a Queen of the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, was discovered in 1912 by a German team led by archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt in Minya governorate. Borchdart illegally smuggled the sculpture out of Egypt in 1913, in breach of conventions on archaeological finds.

At the time, foreign archaeologists were required to hand over antiquties regarded to be of significant importance. Other smaller finds would be shared between the foreign teams and the Egyptian Museum.

Having been discovered in the workshop of Thutmose, who was also known as ‘The King’s Favourite and Master of Works, the Sculptor Thutmose’, the work is highly regarded both for its aesthetic value and the prominence of its maker.

Germany, however, disputes that the bust was taken illegally and says that it was acquired as part of Borchardt’s share of the finds.

Egypt has attempted since the early 1920s to retrieve the bust from the Germans without success, according to a recent report by Al-Monitor.

In 2009, the refurbished Neues Museum in Berlin celebrated its reopening, with the bust of Nefertiti prominently displayed as one of its main attractions. The celebration coincided with one of the Egyptian government’s repeated pleas for the official return of the bust to Egypt. The museum has staunchly refused to give up the sculpture, asserting that the bust was acquired legally by the German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt in 1912. Borchardt had excavated it along with several other objects from the studio of the ancient Egyptian sculptor Thutmose, and had brought his finds to Germany as part of an agreement with the Egyptian Antiquities Service. While there is no proof that Borchardt’s dealings were explicitly illegal, as early as 1925, the Egyptian government began to take issue with Germany’s possession of valuable antiquities by imposing sanctions, and the bust has been the source of tension between the two nations ever since.