Good Morning POU! We continue looking at the “Nadir of African American History” (also referred to as the Nadir of American Race Relations) historical period.

Remember the poem by William Frank Fonvielle after his travels across the south in 1893 to provide a first hand account of the state of black people during this period:

“Somewhere.”

Is there a place that hides from sight

Where daytime never turns to night?

Somewhere, somewhere?

There must be, else we could not bear

The pain, the anguish we have here.

Tell me! Tell me! Is it not true?

A place exists where we’re made anew,

Somewhere, somewhere?

Well, for two million black southerners, that “somewhere” was in northern cities. Roughly 25% of the South’s black population left in two decades (the first Great Migration) rather than submit to Jim Crow’s dangers.

They then participated in local and national politics a safe distance from the South in the hopes that some day they would bring national political pressure against Jim Crow back home.

Many blacks voted with their feet and left the South to seek better conditions. In 1879, Logan notes, “some 40,000 Negroes virtually stampeded from Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, and Georgia for the Midwest.” More significantly, beginning about 1915, many blacks moved to Northern cities in what became known as the Great Migration. Through the 1930s, more than 1.5 million blacks would leave the South for lives in the North, seeking work and the chance to escape lynchings and legal segregation. While they faced difficulties, overall they had better chances there. They had to make great cultural changes, as most went from rural areas to major industrial cities, and had to adjust from being rural workers to being urban workers. As an example, in its years of expansion, the Pennsylvania Railroad recruited tens of thousands of workers from the South. In the South, alarmed whites, worried that their labor force was leaving, often tried to block black migration.

During the nadir, Northern areas struggled with upheaval and hostility. In the Midwest and West, many towns posted “sundown” warnings, threatening to kill African Americans who remained overnight. These “Sundown” towns also expelled African-Americans who had settled in those towns during Reconstruction and before. Monuments to Confederate War dead were erected across the nation – in Montana, for example.

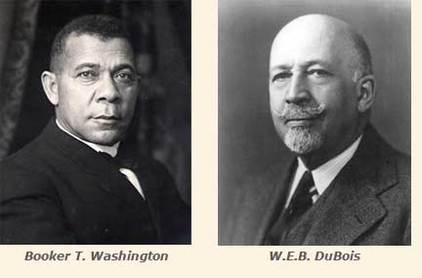

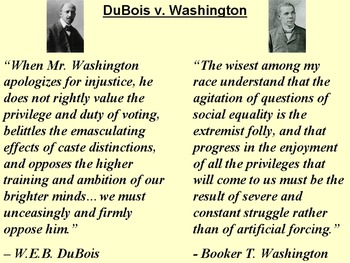

Those African Americans who stayed behind in the south, found themselves virtually banished from local elections by 1905, but that didn’t mean that they weren’t political actors. While we tend to think of Booker T. Washington as an accommodationist because he acceded to segregation in his famous Atlanta Exposition Speech, he remained active in national Republican Party politics until his death. He fought against disfranchisement whenever he could, albeit behind the scenes. Washington relinquished the right to a classical education in that speech, but he coupled that concession with the demand that black people be hired in new southern factories. His white listeners heard and heeded only his concessions. Washington had to plot behind the scenes against the spread of white supremacy. His stealthy politics, meant to be invisible to white southerners, earned him the nickname “the Wizard of Tuskegee.”

Washington’s campaign to fight white supremacy involved what he, and historians since, have called “uplift.” If southern African Americans obtained practical educations, they could support themselves and lead sober lives marked by achievement. They would practice “uplift”—or betterment—first for themselves, then for their less fortunate black neighbors. Surely, they hoped, white southerners would recognize their contributions and capabilities. Gradually robust white supremacy would wither. Washington founded the National Negro Business League to promote and publicize black commerce and self-help.

Northern-born black sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois positioned himself as Washington’s opposite. Du Bois had graduated from Fisk University in Tennessee and earned a Ph.D. at Harvard. By 1902, Du Bois believed that Washington had conceded too much. Any man should be able to have a classical education. Moreover, to accept segregation would be to give up all civil rights since accepting separation acknowledged that black people were not equal. Du Bois founded the Niagara Movement in 1905, the forerunner of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

While it works well in the classroom to set Washington and Du Bois against one another in a debate, it is important to understand that they were never really the polar opposites that they (and white journalists) made themselves out to be. Indeed Washington’s “uplift” philosophy is virtually the same idea as Du Bois “talented tenth” philosophy in ideal outcomes. Each man’s strategy must be contextualized chronologically and by its applicability to the South or the North. Moreover, African American opinion ranged widely between the two men’s positions.

The Great Migration resulted in a blossoming of black culture in northern and mid-Western cities, and African Americans began to speak of the “New Negro.” He or she was born after slavery, well-educated, independent, and proud of his or her African background. The New Negro saw World War I as the “Great War for civil rights.” When it ended, Du Bois announced: “We return from fighting. We return fighting. Make Way for Democracy.” African Americans had fought “the savage Hun;” now they returned to fight “the treacherous Cracker.” Across the nation, whites met those demands with violence. Twenty-six full-fledged racial massacres occurred in the summer of 1919.

Suffrage for me, not for thee

Many white male politicians and some white southern women fought woman suffrage after World War I because they feared that it would bring African Americans back into the electoral process. One white Congressman who opposed it remarked, “My cook would vote while my wife would not.” But many southern white women supported woman suffrage; a very few supported black women’s right to vote.

When the Nineteenth Amendment granting woman suffrage became law in the fall of 1920, black women across the South attempted to register and vote, with varying degrees of success. They acted as a wedge to bring African Americans back into public life. After 1919, black and white southerners of both sexes forged tentative coalitions to prevent a recurrence of such violence. Called Commissions on Interracial Cooperation, black and white members worked to put an end to racial massacres and lynching and toward better “race relations.”

Black housing was often segregated in the North. There was competition for jobs and housing, as blacks entered cities which were also the destination of millions of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe. As more blacks moved north, they encountered racism where they had to battle over territory, often against ethnic Irish, who were defending their power base. In some regions, blacks could not serve on juries. Blackface shows, in which whites dressed as blacks portrayed African Americans as ignorant clowns, were popular in North and South. The Supreme Court reflected conservative tendencies and did not overrule southern constitutional changes resulting in disfranchisement. In 1896, the Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that “separate but equal” facilities for blacks were constitutional; the Court was made up almost entirely of Northerners.

While there were critics in the scientific community such as Franz Boas, eugenics and scientific racism were promoted in academia by scientists Lothrop Stoddard and Madison Grant, who argued “scientific evidence” for the racial superiority of whites and thereby worked to justify racial segregation and second-class citizenship for blacks.

Numerous blacks had voted for Democrat Woodrow Wilson in the 1912 election, based on his promise to work for them. Instead, he introduced the re-segregation of government workplaces and employment in some agencies. The first feature length-film, The Birth of a Nation (1915), which celebrated the rise of the first Ku Klux Klan, was viewed by President Wilson at the White House.

In 1920, virtually all white southerners believed that segregation and white supremacy would last for another thousand years. They thought that they had found a permanent solution to the “race problem.” But their permanent solution barely lasted another decade.

By 1933 black southerners began to challenge southern disfranchisement and segregation on the ground, in the courts, and, even at the ballot box in Upper South cities. The federal government finally responded in a limited way to southern poverty and racism with some aspects of the New Deal, and northern black voters began to elect representatives to Congress who spoke for southern African Americans as well. Forty years after William Frank Fonvielle tracked the spreading stain of white supremacy across the South, it began to recede ever so slightly.