Although the “Nadir of African American History” is defined around the institutionalized racism embedded into each level of government, specifically to erase any gains made by the children of slaves immediately following the Civil War, there were actual gains made during this time.

Black literacy levels, which rose during Reconstruction, continued to increase through this period. The NAACP was established in 1909, and by 1920 the group won a few important anti-discrimination lawsuits. African Americans, such as Du Bois and Wells-Barnett, continued the tradition of advocacy, organizing, and journalism which helped spur abolitionism, and also developed new tactics that helped to spur the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. The Harlem Renaissance and the popularity of jazz music during the early part of the 20th century made many Americans more aware of black culture and more accepting of black celebrities.

The years between 1877 and 1915, as UC Irvine Prof. Dickson D. Bruce Jr. points out in his book, however, was a period of such rancorous white racism that it was labeled the “nadir” of black American history.

The period from the end of Reconstruction to World War I was a time that witnessed the disfranchisement of black voters throughout the South, the rise of legislation in the South designed to segregate blacks in everything from housing to transportation and an increase in racial violence against black people (nearly 200 lynchings a year throughout the 1890s). Such practices were supported by a racist ideology fueled by blatant stereotypes in American popular culture of black inferiority and dependency and an alleged tendency among blacks for criminality, sexual brutality and violence.

But from this low point in American race relations arose black voices: poets, novelists and short-story writers whose work confronted the conditions of an increasingly racist society.

As Bruce writes in “Black American Writing from the Nadir: The Evolution of a Literary Tradition, 1877–1915” (Louisiana State University Press):

The virulence of white racism was a powerful spur to literary activity as black writers sought to use their pens to fight against racist practices and ideas.”

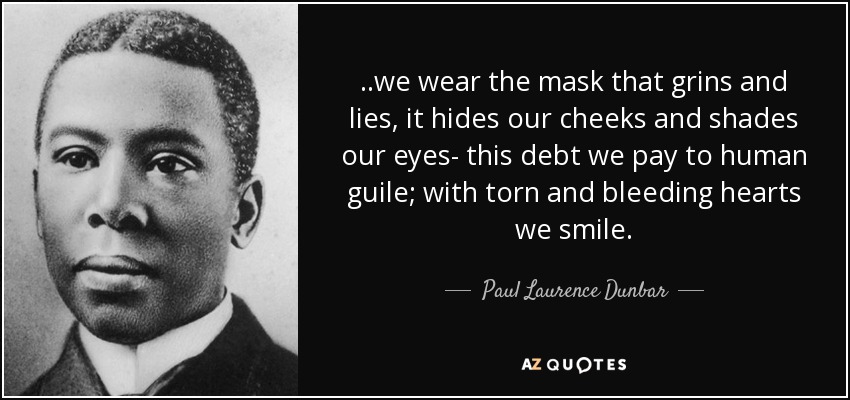

Among the significant black writers to emerge during this period were Charles W. Chesnutt, Paul Laurence Dunbar, James Weldon Johnson, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, W.E.B Du Bois and dozens of obscure minor authors.

Mostly members of a small but growing black professional class–teachers, ministers, lawyers, doctors and businessmen–these writers not only challenged racist attitudes but used their writing to, as Bruce says, “educate people about the character and accomplishments of blacks in America.”

“They were showing the rest of American society that they were good Americans: They themselves were like other people in American society and therefore they shouldn’t be excluded from American institutions and American life,” said Bruce, 43, a professor of comparative culture.

Bruce, whose book grew out of his work in dealing with race relations and racial ideologies, said “Black American Writing from the Nadir” is aimed primarily at an academic readership, “although other people could certainly read it.”

By examining black literature of this period, Bruce said he thinks it “helps to tell us more about how American race relations have developed, and I think that it provides a useful background for understanding what the nature of race relations continues to be.”

Bruce, who has taught at UCI for 18 years, began working on “Black American Writing From the Nadir” in 1983. The majority of his years of research was conducted at the Library of Congress and Howard University in Washington.

“One of the things that surprised me was how much writing there was,” said Bruce, who turned up nearly 100 volumes of poetry and about 50 works of fiction written by black writers between 1877 and 1915. He said that doesn’t include all the fiction and poetry written in periodicals and newspapers, which he also examined for his study.

In looking at the work of black writers during this period, Bruce said, “you see changes in the literature that corresponded to changes in American society itself.”

“You could see a growing sense that the kinds of stereotypes that whites had and the kind of segregated society whites wanted to create was going to be hard to oppose,” he said. “If you look fairly early on a lot of the black writers were optimistic and tended to believe, by their achievements and arguments, that they could have some effect on white society and fight these stereotypes. As the years went on, you saw less optimism that whites could be persuaded to change these attitudes.”

“And that’s not surprising given the kind of world these writers were living in,” he said.

Although many of the black writers were relatively unknown outside their local areas, Bruce said Chesnutt, Dunbar and several others had wide audiences.

“In fact,” he said, “some people claimed that Dunbar was probably among the most popular writers in poetry in the United States during this period in terms of the kind of audience he reached.”

Bruce, whose three previous books dealt with the pre-Civil War South, is currently working on a biography of one the writers he examined in “Black American Writing From the Nadir”: attorney Archibald Grimke, a political figure and diplomat who was one of the early leaders of the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People.