The Costs of White Patronage

This extraordinarily rich cultural moment, the Harlem Renaissance, in which it seemed possible that African Americans would take the lead in creating the cosmopolitan America that progressive writer Randolph Bourne had called for in the 1910s, won the attention and admiration of a good many white critics and intellectuals. In particular, writer H .L. Mencken and previously featured Negrotarian, Carl Van Vechten, became champions of the Harlem Renaissance, devoting themselves to publicizing and defending the cultural and literary achievements of black writers, poets and novelists, whether asked or not.

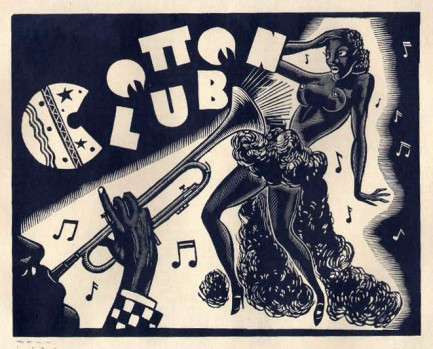

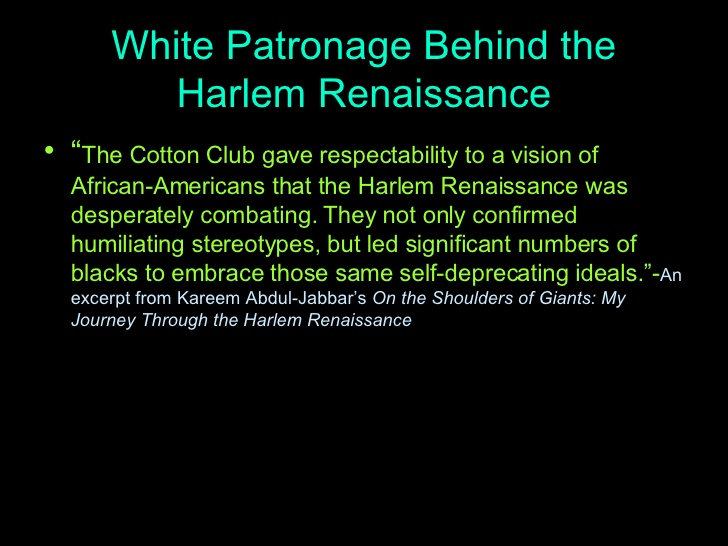

However, white support for the Harlem Renaissance came at a price. White patronage, white publicity for the black writers, musicians and artists, white interest in what was going on in Harlem, led white New Yorkers from downtown up to Harlem to attend jazz clubs that blacks themselves could not attend. It turned Harlem into a sensation, a phenomenon, an event—something that Americans elsewhere in the country read about in mass-produced newspapers and magazines. Such publicity and support increasingly made the Harlem Renaissance financially dependent on white patronage. Blacks lacked the economic institutions and simply the money to support a full-scale cultural renaissance of this kind. As the twenties wore on, more and more black artists and writers came to resent their reliance on white economic support and the patronizing attitudes they encountered in some of their supporters.

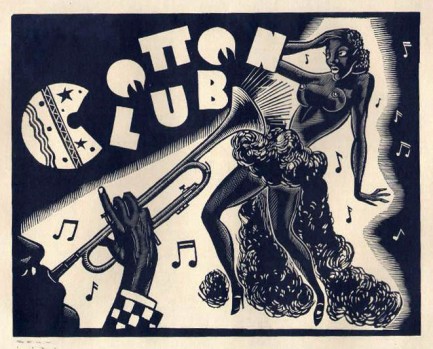

White writers and white popular culture as a whole mobilized African American music and culture in ways that reinforced racist stereotypes and opened the door to a new kind of popular culture that, ironically, was available to whites only. White critics such as Van Vechten and Mencken were genuinely enthusiastic about the Harlem Renaissance; they wanted to use the influence and power they had in journalism and in American intellectual circles to promote black culture. But their promotion came at a cost. They often presented the achievements of blacks as deriving from the inherent primitivism or emotionalism of African American culture, suggesting that whites should turn to black culture in order to free themselves from whatever remained of the Victorian constraints of their parents and grandparents.

This notion that black culture was to be admired primarily for its emotionalism and primitivism worked hand-in-glove with a consumer culture that promoted the immediate gratification of impulses and instincts as the way to live a good life. Moreover, such characterizations of African American culture did little to assist the political aspirations of activist intellectuals like W.E.B. Du Bois and other political figures in the African American community, who wanted to make the case for full citizenship for blacks on the grounds that African Americans were fully capable of rational self-government. Too much of the publicity about the Harlem Renaissance seemed to play into the worst assumptions of white people—even those whites who were willing to give jazz a listen.

White capital and influence were crucial, and the white presence, at least in the early years, hovered over this New Negro world of art and literature like a benevolent censor, politely but pervasively setting the outer limits of its creative boundaries.

Much attention has been paid to the many complex relations between white patrons and the leading lights of the Harlem Renaissance, the possible effects of financial and other types of sponsorship provided by these patrons on the representation of African American culture and identity, and even the success of the movement itself. For African American novelist Zora Neale Hurston, these Lost Generation “Negrotarians,” as she christened white patrons of African American art, fell into different categories: the earnest humanitarians with sincere interest in the work and careers of black writers, and those who, in David Levering Lewis’s words, “were drawn to Harlem … because it seemed to answer a need for personal nourishment and to confirm their vision of cultural salvation coming from the margins of civilization”. The demands of this latter group often led to artistic conflicts on the part of African American writers, as Ralph D. Story suggests:

For the Harlem Renaissance writers and painters, once they agreed to a patron-artist relationship-especially a financial one–it seemed to obligate them to produce a certain kind of product that would meet the patron(s)’ approval. Hence, it is difficult to imagine just what kind of art might have been produced had not the artists been under such covert pressure to please their supporters.

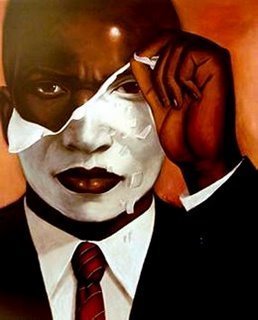

For Marcus Garvey, the influence such patrons wielded accounted for what he considered the denigrating representation of black culture in Harlem Renaissance texts such as Claude McKay’s Home to Harlem (1928). In a severe and unsympathetic review of this novel (as well as, among other works, Eric Walrond’s highly acclaimed Tropic Death, 1926), Garvey alleges this:

“The white people have these Negroes to write the kind of stuff that they desire to feed their public with so that the Negro can still be regarded as a monkey, or some imbecilic creature”.

In his judgment, Home to Harlem was a “veritable libel” against the Negro and writers like Walrond and McKay little more than “literary prostitutes” who had “done damaging harm to the morals and reputation of the black race.” He added,

“Whenever authors of the Negro race write good literature for publication the white publishers refuse to publish it, but wherever the Negro is sufficiently known to attract attention he is advised to write in the way that the white man wants”.

Garvey was not alone. Other critics accused the literary and musical revolutionaries of the Harlem Renaissance of tailoring their work to appeal to white audiences. The intent of the Renaissance was to create more equality for African Americans at white publishing houses, but this came with the cost of the inability to express themselves despite what white audiences thought. Also, only the African-American musicians that appealed to white audiences had access to mainstream popularity and success, which may have unduly influenced the musical genre.

In the aftermath of the era, critics have argued that the Harlem Renaissance helped to fuel further separation of the New Negro against the rural and uneducated African Americans in the south. After the Renaissance heyday, the Harlem neighborhood sunk back into poverty, leaving some to wonder if the Harlem Renaissance was more of a romantic era than a catalyst for change.