Good Morning POU.

We continue to look at some of the murder cases that remain unsolved from the Civil Rights Era. Today’s case is about two very brave men that sadly made history as firsts and were brutalized for it.

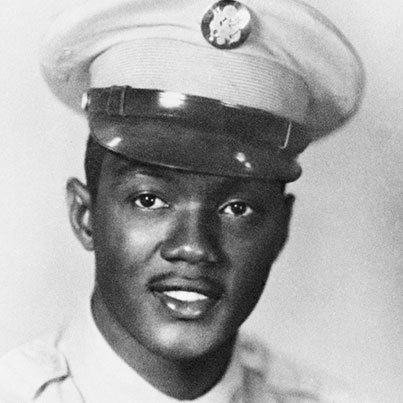

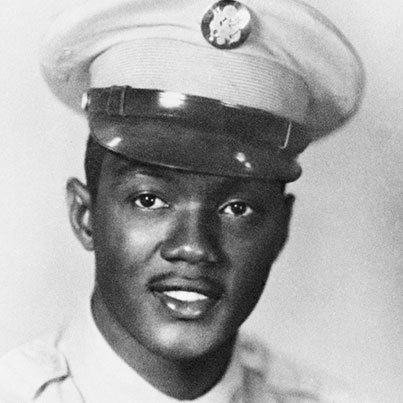

On June 2, 1965, in a horrifying display of the ongoing racial tension in the area, one of the two first African American deputy sheriffs of Washington Parish, Louisiana, was shot and killed while on patrol.

Deputy O’Neal Moore and Deputy David “Creed” Rogers had been on the force for one year and one day when they—the two first African American sheriffs on the force—were ambushed by a group of white men driving a truck with a Confederate flag decal. Gunfire killed Moore instantly; Rogers was shot in the shoulder and lost an eye, but survived.

Although suspects were arrested, no charges were filed, and the case lay dormant for decades. It has been reopened three times, beginning in 1990. Prime suspect Ernest Ray McElveen, a known white supremacist, died in 2003 without ever being tried; while law enforcement officers believe there were two other men involved who may still be alive, they have so far been unable to move ahead with the case.

The shocking display of racial hatred brought to the nation’s attention the discrimination and violence African Americans faced in their daily life in Louisiana and other parts of the South, further mobilizing civil rights activists to fight for equality (and, on a more basic level, safety). Moore’s courage in remaining on the force amidst threats of violence for a full year before he was killed remains an inspiration to this day. (And in fact, Rogers completed a full career in law enforcement, despite his partner’s murder.)

They buried Moore a week after the shooting, on a stifling hot June afternoon, the New Zion Missionary Baptist Church so chock-full of mourners that those who could not fit inside gathered under spreading trees in the churchyard. He was married in that church, and he sang in the choir.

Seven women fainted at the funeral, including the widow, the newspapers reported. “I can’t go on without him,” she cried. Her four daughters, the oldest 9, the youngest 9 months, sat silently up front.

Maevella Moore, widow of slain black Deputy Sheriff O’Neal Moore, weeps at her husband’s funeral near Bogalusa, June 9, 1965. At left is Stephen Moore, father of the victim.

When the mourners marched with the coffin down Jones Creek Road to the black cemetery, a sudden rain and hailstorm drenched them.

The streets were flooded in Bogalusa, Washington Parish’s largest city, seven miles south of Varnado, where that evening the black activist James Farmer, national director of the Congress of Racial Equality, spoke at a rally. He proclaimed that the shooting was “the Klan’s bloody answer” to a local voters’ league request that more blacks be hired as law enforcement officers.

He was speaking to the true believers. Black residents in Washington Parish for some time had been agitating for a greater role in their community: more jobs, fair housing, equal rights.

In the weeks leading to the shooting, they had staged rallies and marches, demanding that public facilities be desegregated. A large force of state troopers was brought in to quell any disturbances and try to keep the demonstrators safe. By the time the two officers were shot that night, about 50 whites had been rounded up for attacking or harassing blacks.

The local Ku Klux Klan was a potent force, so entrenched that many members seldom bothered to hide beneath hoods. Indeed, that year a Georgia congressman addressed the U.S. House of Representatives and named several hundred white men in Washington Parish that court records indicated belonged to the Klan or other white supremacy organizations.

“The Ku Klux Klan uses three basic techniques: secrecy, terror and intimidation,” said Rep. Charles L. Weltner, a white Democrat.

The Klan and members of the ultraconservative Anti-Communist Christian Assn. were particularly enraged at the sight of two black men in deputy uniforms, driving around the parish in a county patrol car. They denounced the white sheriff and accused him of “selling out.”

Lou Major Jr., today the white publisher of the community’s largest newspaper, the Daily News, a job he inherited from his father, can sometimes still feel the tension from those days.

“The Klan was pretty active,” he recalled. “They did quite a bit of cross burning in front of our newspaper. I can think of four that were burned at my dad’s home too. The radio station, which happened to be owned by a Jewish man for a time, it got hit.”

A Klan rally a month after the shooting drew 10,000 whites down to the riverfront, no small gathering for Bogalusa, population 26,000. They burned three crosses, and 50 Klan leaders paraded, not all in hoods and robes. Half a dozen speeches fired up the night.

“Look how far we’ve come now,” Grand Titan Saxon Farmer of Bogalusa told the crowd, boasting of the Klan’s growth in Washington Parish in recent years. Before, he said, “it was just me and the man they’re now charging with murder of the Negro deputy sheriff.”

Louisiana’s governor at the time, John McKeithen, a white man, came to Bogalusa and announced a $25,000 reward for information leading to the arrest of anyone else responsible for the slaying.

“We’re going to catch them,” the governor vowed. “We’re going to catch them all.”

An Unsure Witness

Daniel R. “Scrap” Fornea had just gotten home and was climbing the front porch steps when the patrol car drove by. He saw the pickup coming up behind it too, like it wanted to pass, and–he wasn’t sure–but “there could have been five, two, or one person in it. I just don’t know.”

He ran to where the patrol car had smashed into a tree. Deputy Moore lay dead, his body straddled over his partner. Deputy Rogers was making frantic radio calls to the dispatcher, describing the truck and the Rebel flag on the bumper.

“That’s about all I know,” Fornea recalled. “Except we thought of them deputies as good Negroes.”

The deputies had been headed to Moore’s home for a late dinner of fried catfish that Maevella was preparing. They were diverted at the last minute by a report of a suspicious brush fire. It might well have been a ruse, because moments later they were shot, every window of their cruiser blown out.

An hour later, McElveen, a paper mill employee and insurance salesman, a respected member of the community who was active in white power groups, was pulled over in Tylertown, Miss., an hour’s drive from the shooting.

(Click for Page 2 below)