A Wife’s Pain

Maevella Moore, now 75, is like any doting mama and grandma. She beams with pride when she talks about her grandchildren, about how the kids and grandkids have gone to college and married, and how one grandchild is in law school. She’ll say how she’s even a great-grandma now to a 7-year-old.

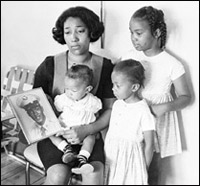

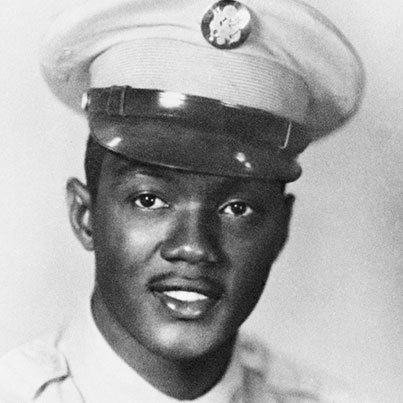

And like a proud wife, she talks about her husband. She’ll tell you about how O’Neal Moore worked the late shift as one of the first black deputies of the Washington Parish (La.) Sheriff’s Office. She remembers how he’d be quiet when he got home at 2 a.m. so as not to wake their young daughters, then ages 9, 7, 4, and 9 months. She laughs when she talks about how the next day, the children “would run and jump on him, calling out, ‘Daddy!’ …He loved those four little girls,” she says.

But the laughter quiets and the voice fades when she talks of that terrible night 45 years ago.

On June 2, 1965, Dep. O’Neal Moore and Dep. David “Creed” Rogers were patrolling near their homes in Varnado, a very small town on the Mississippi border. The deputies were driving on Main Street, crossing railroad tracks, heading for a stop at the Moores’ house, where Maevella had cooked catfish.

They never tasted Maevella’s dinner.

A dark pickup truck with a Confederate flag decal on the front bumper passed them. It would be the last thing Dep. Moore saw. Three suspects in the truck unleashed a hail of gunfire, ambushing the two black deputies.

When the spray of bullets from rifles and shotguns ended, 34-year-old Moore lay dead, the back of his head blown out, slumped over his partner Rogers. He had served for exactly one year.

Rogers was hit in the shoulder and lost an eye. He continued serving the Sheriff’s office and died in 2007 at 84.

Arrest But No Trial

The attack on the two deputies brought nationwide attention to Varnado and nearby Bogalusa. FBI agents, Louisiana State Police, and student civil rights workers swarmed the parish.

It wasn’t long before police in Tylertown, Miss., stopped a truck fitting the description. Officers found pistols in the truck but no shotgun or rifles.

The driver was Ernest Ray McElveen, a paper mill worker from Bogalusa. McElveen was a member of the White Citizens Council, the National States Rights Party, and an honorary member of the Louisiana State Police. He was arrested and charged with murder, but within several days, friends bailed him out, putting up $25,000.

McElveen was never tried. Officials said they lacked enough evidence to pursue the case.

Retired FBI agent Frank Sass-who died last November-discussed the case in 2002. “If we in the Bureau could have gotten to McElveen before they turned him over…we might have gotten something out of him,” Sass told a reporter from the Los Angeles Times.

Sass told the Times that when agents tried to interview other suspects, they didn’t succeed. “They were all provided alibis, for themselves and everybody else they knew.”

The case has been reopened several times, as new information was brought forth.

But that seems unlikely, given how Washington Parish has managed to live with its secret for so long. Some shop owners won’t even put up the reward posters.

Varnado sits in the northeast corner of Washington Parish, a lumber and paper mill town just off the Pearl River where Louisiana meets Mississippi, an hour north of New Orleans. The hamlet is still little more than a mix of gas stations, a beauty salon, a takeout pizza place and a smattering of churches. The old Gulf, Mobile & Ohio railroad tracks, now the Illinois Central Railroad, still cut through town.

It is not a community where new ideas readily take hold. As soon as the case was reopened, Moore’s widow, Maevella, got another death threat. Even Rogers, now 80, who with a glass eye went on to complete a long career as a local deputy, said: “I’ve pretty well learned not to think about it too much anymore. I’ve made up my mind I’m never going to find out who did this to us.”

David “Creed” Rogers died in 2007 never knowing who killed his partner and shot him.

Said Frank Sass, a retired FBI agent who worked the case at the time: “You’re whistling in the dark about anything to do with that case now. I just don’t think it will go anywhere. Once McElveen and everybody else stopped talking, this whole thing came to a screeching halt.”

“Over the years, we’ve had promising leads. The FBI went to elaborate means. We have run down every lead and fully investigated. We’re asking now for someone [to come forward],” says Howard Schwartz, assistant special agent in charge in the New Orleans division of the FBI.

In 2003, McElveen died at age 79 in Washington Parish. But that didn’t close the case. Authorities believe two other suspects may have been involved in the shooting, and it’s these accomplices that the FBI still seeks.

A Dark and Deadly Time

Many in Louisiana believe the Moore shooting was a Ku Klux Klan operation. The Klan was very powerful in the region at the time, with an estimated 3,000 members.

“The KKK killed that officer, that’s definite,” says Washington Parish Sheriff Robert Crowe, son of Sheriff Dorman Crowe, the man who hired Moore and Rogers as the department’s first black deputies.

Authorities believe the Klan was involved in Dep. Moore’s murder because it was just one of many violent incidents in the Bogalusa region at the time and the Klan was behind many of the others. “Bogalusa was one of the worst areas during the Civil Rights Movement. That was a terrifying place,” says Mark Potok of the Southern Poverty Law Center. Potok’s assertion is backed up by records that reveal Bogalusa’s streets were the setting for confrontations between Klansmen and the Deacons of Defense and Justice, armed black vigilantes.

“There had been shootings and the people were defending themselves. Men were organizing to protect their homes, families, and the civil rights workers that were in town,” says Marvin Austin, a retired two-term city councilman, Vietnam veteran, and president of the Bogalusa Voters League.

Maevella Moore says it was the Deacons who protected her after she received a telephone death threat following the murder of her husband. “These were men of quality, the Deacons. They were by my side and took me to where I needed to go,” she says.

Retired FBI agent Alan Ouimet, who was sent to Bogalusa on temporary assignment in the Civil Rights Era, remembers what it was like to investigate cases in such a tense environment. “There was this umbrella of violence that caused fear on both sides,” he says. “It wasn’t unusual to knock on the door of a black person or a white person and see fear on their faces. Then I would turn around and see a car with two Klansmen in it watching our movements.”

Ouimet says that it was very hard to gather information on the Moore murder in that climate and that even police officers were not keen on investigating the cop killing. “Various things were at work,” he says. “The tempo of the times would preclude interest on the part of a lot of police officers and civilians who were against the Civil Rights Movement.”

Ouimet also believes there were Klansmen within the Bogalusa PD. And statistically that’s likely.

According to Mississippi’s Jackson Clarion-Ledger, Washington Parish had more Klansmen per capita than any other place in the U.S. during the era. Black residents told of night-riders who shot up cars and homes. Whites who got in the Klan’s way were also attacked. The home of Dep. Doyle Holliday-who helped lead the investigation into the Moore murder-was fired on right after the incident.

Doug Holliday, Doyle’s son who was “10 or 12 at the time,” remembers. “I had gone to bed, and Mother had made sandwiches and was waiting up for Daddy. I heard Daddy drive up. I remember hearing the shots, him telling Mother to get down, and then he took off shooting at them. I was scared to death.”

Breaking the Barrier

Washington Parish Sheriff Robert Crowe was 18 in 1965. And he remembers his father hiring Moore and Rogers. “He needed help,” Sheriff Crowe says. “We caught a lot of negative remarks for hiring the first two [black officers].” But he adds that his father was willing to take the heat in order to fill a need. “[He realized that] you need the different ethnic groups otherwise you’re missing out on lots of information.”

Moore’s widow says the sheriff hired Moore and Rogers in order to appease the black community. “The sheriff’s department hired them just to shut people up,” says Maevella Moore. The hiring made black citizens happy. But it enraged some in the white community. “There was a lot of pressure, but my husband was not afraid of anything. He was not a scaredy-cat.”

Ouimet says that Moore knew he was in danger. “Through informants, O’Neal was warned that he was a target for assassination. He could have left the Sheriff’s office but refused to do so.”

Ouimet remembers Moore fondly. “The limited amount of time I spent with him, he appeared to be a very gentle, soft-spoken soul, who loved his job as a deputy. I am sure he was proud to be the first [black man] in the parish to attain such a position. He was proud of his color and his position.”

If Moore knew the Klan planned to kill him, he didn’t let on to his wife, knowing she was a worrier.

“As far as what he did [on the job], my husband didn’t talk to me [about it]. He would always say he was having a good day… He never discussed his job,” Maevella says.

A Tough Case

From the beginning, the Moore murder was a difficult case to crack. It won’t be any easier for today’s investigators.

“Most of the people are deceased. It’s a very tough case to solve,” Sheriff Crowe says. “They were on the verge of breaking the case back then-within 12 months of the shooting-but could never get quite enough to put it together.”

Marvin Austin says he wouldn’t be surprised if law enforcement officers were involved. “Somebody had to know [Moore and Rogers] were patrolling.”

Despite his suspicions, Austin says he can’t identify any specific suspects. But he believes the key to the case lies in the soul of an uninvolved officer who knew the culprits and has kept his secrets for 40 years. And he has a plea for that officer: “Think about your family; if this happened to you, you would want justice…for your family. Just put yourself in the shoes of Moore’s and Rogers’ families,” Austin says, addressing that retired officer.

FBI assistant special agent in charge Schwartz isn’t as sure as Austin that law enforcement officers were involved in the murder, but he believes it’s possible some retired local officer may know something about the case. “This case shouldn’t be looked on as simply a racial matter; it’s the murder of a law enforcement officer,” he says. “Every officer in the U.S. should be outraged and want to do everything to bring this to justice.

“To anyone who was former law enforcement in 1965 and has long since retired-you swore an oath to the badge… Do the right thing and report it,” Schwartz says.

In the tiny rural town of Varnado, population 342, Maevella Moore still lives in the house she shared with O’Neal. She raised her children and was married again from 1983 to 1998. She worked as a nurse, retiring in 1999. She still wanted to be with people, so she has toiled at the fabric and art department at the local Wal-mart.

Maevella has kept Dep. Moore’s picture on her wall. She wonders who murdered her husband, a man who gave his life for public safety at a time when many people in his local community did not appreciate his courage nor desire his service. And she waits for someone to step up and do the right thing.