TGIF POU!

Sadly, today’s feature in our series, has had very little written about her historic role in the Negro Leagues. There isn’t even a photo of her. Before Effa Manley, there was another woman that would own a Negro League team.

Olivia Taylor

In 2006, the Baseball Hall of Fame’s Negro Leagues Committee selected Newark Eagles’ owner Effa Manley for induction into the hallowed hardball shrine.

The move made Manley — who is widely known in the community of Negro League fans and historians as a precedent-setting, trailblazing, hard-nosed woman in a man’s business — the first and so far only female elected to the Hall. From the mid-1930s to the late 1940s, states Manley’s entry on the Hall of Fame website, Manley used her position to push for African-American civil rights and racial equality.

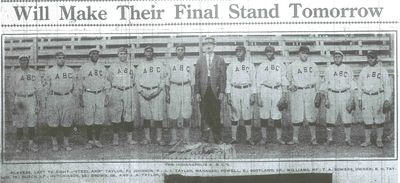

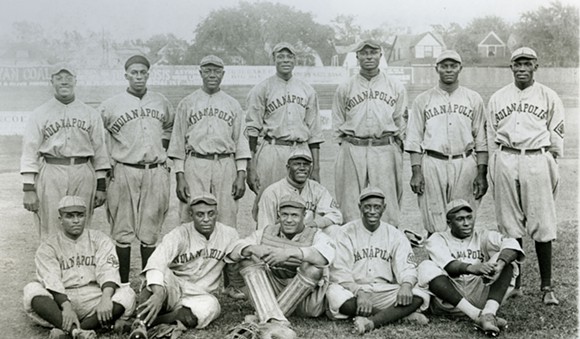

But more than a decade before Manley piloted the Eagles, Olivia Taylor took over ownership of the Indianapolis ABCs after the sudden death of her husband, C.I. Taylor, a beloved pillar of the nascent Negro National League. The unfortunate happenstance made Taylor, not Manley, the first woman to own a top-level Negro Leagues team.

But while Manley received a plaque in Cooperstown, Taylor was buried in an unmarked grave in Indianapolis’ Crown Hill Cemetery. Effa Manley has become a baseball legend; Olivia Taylor an overlooked, forgotten historical footnote, a fact symbolized by Taylor’s undignified final resting place.

“Olivia was a fearless woman, cut in the mold of Madame CJ Walker,” says Negro Leagues researcher Paul Debono, who authored a book about the history of the ABCs “Olivia stepped into her widow’s role after C.I.’s premature death … unafraid [of] the rowdy raucous world of black baseball. She stood her ground with the bosses of the Negro League including the big man, [Negro National League founder] Rube Foster.

“Olivia has been overlooked in local lore,” Debono adds. “Her role in local baseball history has been mostly unknown, underestimated and forgotten.”

The Rise of the ABCs

The woman who would become a baseball trailblazer was born Olivia Harris in about 1884, the first child of James and Pollie Harris of Birmingham, Ala.

It was in Birmingham where, in all likelihood, Olivia met Charles Isham Taylor, a South Carolina native and rising star in the black baseball community who founded and owned the Birmingham Giants team in 1904.

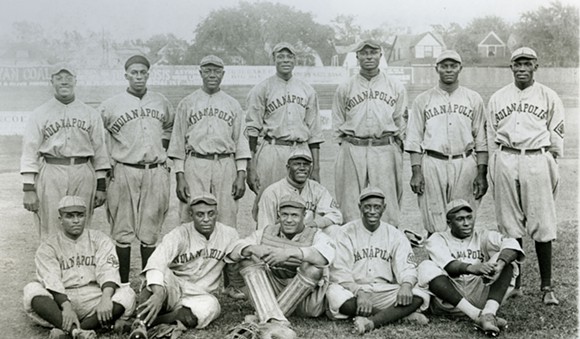

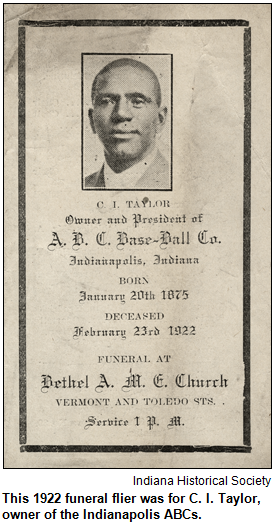

It’s unclear when exactly Olivia Harris married C.I. Taylor, but newspaper accounts peg the date around 1910.C.I. built the ABCs into a hardball powerhouse, after taking ownership in 1914 and in 1920 he helped Andrew “Rube” Foster found the Negro National League, the first sustained, long-term circuit of black baseball teams in history. At the time, the couple was living at 446 Indiana Ave. with their son and four lodgers, including ABCs pitcher William “Dizzy” Dismukes.

In February 1922, C.I. died suddenly at the age of 47, thrusting Olivia into the role of team owner. Conflict between her and ABCs manager Ben Taylor, C.I.’s brother, began almost immediately, with Ben chafing at his sister-in-law’s ownership of his brother’s life passion.

Along with Ben, Olivia attended the annual NNL league meeting in December 1922 in Chicago; media reports listed Olivia as “Mrs. C.I. Taylor.” She returned home to Birmingham for a visit a month or two later, and the 1923 baseball season seems to have more or less passed uneventfully.

It was before the 1924 season that Taylor’s troubles began, in the form of player dissent and the raiding of her squad’s roster by clubs in the eastern part of the country. She was accused of underpaying the squad’s members, and Taylor and Dismukes traded vitriolic, sarcastic letters to the editor in the national black press.

A spate of early-season rain damaged the ABCs’ financial status, forcing the cancellation of numerous buy viagra gold games, and several players left the club. While Taylor was visiting family in Alabama, Dismukes attempted to piece together a decent team.

But even those efforts proved futile, and the whole operation came crashing down later in June, when NNL officials booted the Indianapolis franchise from the league under the argument that the raiding of Taylor’s club by independent teams decimated the ABCs’ roster to the point that the franchise was putting a terrible product on the diamond.

Taylor and the ABCs were allowed to remain associate members of the league and could play exhibition games, but the tone of the league’s announcement was decidedly negative and tacitly suggested that Taylor had ruined C.I.’s great legacy.

In a statement, Taylor asserted the ABCs books were actually in quite good shape, contrary to the league’s claims. She accused Foster — without specifically mentioning his name — of being the ringleader of a cadre of NNL executives who targeted the ABCs for dismantling in order to snap up the franchise’s best players for their own teams. She additionally charged that Foster intentionally fudged the league’s financials to make the ABCs look bad.

“After all, the one big aim was to disorganize the club and prevent them from playing any more games this season,” Taylor’s statement claimed. She then boldly charged Foster and his friends with betraying their own race for the sake of greed.

“The sooner it is realized that all Negroes will not ‘sell out’ for a morsel of bread the nearer we will come to getting what a thing is worth,” she said.

But Olivia Taylor’s three-year run as the owner of a top-level Negro Leagues team was over. While baseball pundits debated both the cause and significance of the ABCs’ demise, Taylor quietly faded from the big-time hardball scene.

After baseball

Now, nearly 90 years later, it remains unclear whether Taylor was either a victim of sexist, jealous male businessmen or simply a paranoid, ill-equipped team owner who was in over her head. The he-said-she-said between her and Foster exists as a matter of perspective and personal opinion. What or who was the exact source of Taylors’s downfall will perhaps never be determined.

Fortunately, Taylor’s story doesn’t end there. As Debono noted in his book, her dealings in the baseball world earned her the respect of the Circle City’s African-American business community; indeed, during her time as ABCs owner, she received letters of support from entities called the Better Indianapolis League and the Indianapolis Negro Business League.

And in 1925, she was elected president of the Indianapolis chapter of the NAACP.

Taylor spearheaded the group’s preparation for hosting the national NAACP’s 18th annual spring conference in Indianapolis in June 1927. With that, she became the first woman to head up the influential and historic NAACP’s national convention.

On April 24, 1935, Taylor’s story came to an end when she died suddenly at the age of 50. Her death received scant attention in the national media.

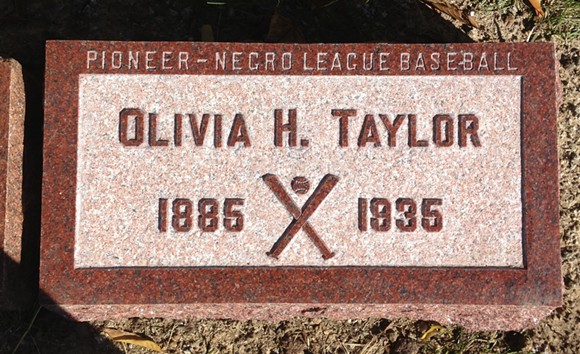

Taylor was buried in the same plot in Crown Hill Cemetery as her husband. Though the baseball community managed to raise funds for a headstone for C.I. in 1922, there was no such effort for his widow, who was interred in an unmarked grave.

But that injustice has just changed. The nationally known Negro Leagues Baseball Grave Marker Project, which has raised funds to place stones at the unmarked graves of dozens of Negro Leagues players, has placed a marker at Olivia Taylor’s final resting place. The development makes Taylor the first owner and first woman to benefit from the NLBGMP’s tireless efforts, and, organizers hope, will set in motion the much deserved recognition Taylor has yet to receive.