Good Morning POU!

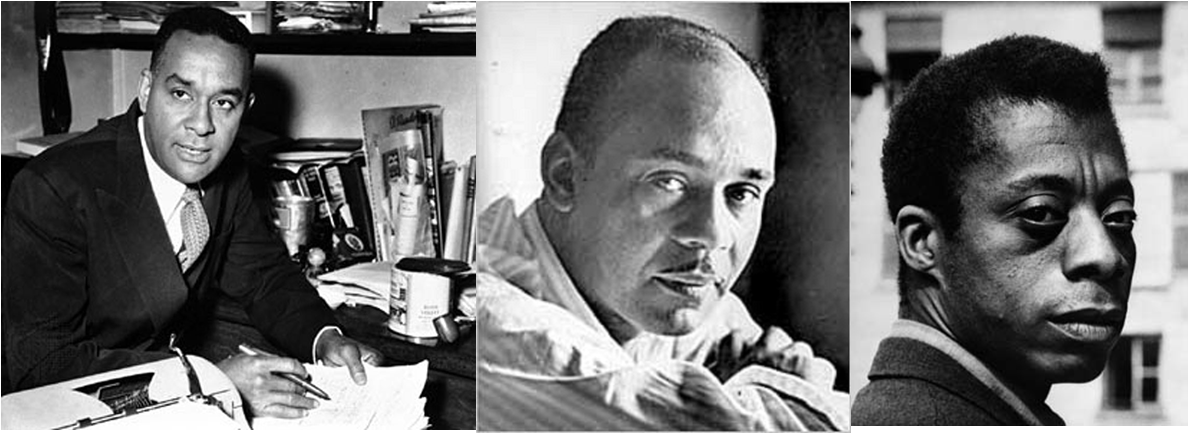

The Indignant Generation is the neglected but essential period of African American literature between the Harlem Renaissance and the Black Arts Movement that began in the 1960s. The years between these two indispensable epochs saw the communal rise of writers such as Richard Wright, Gwendolyn Brooks, Ralph Ellison, Lorraine Hansberry, James Baldwin, Julian Mayfield and many other influential black writers. While these individuals have been duly celebrated, little attention has been paid to the political and artistic milieu in which they produced their greatest works. This generation of African American writers were shaped by Jim Crow segregation, the Great Depression, the growth of American communism, and an international wave of decolonization. Many of them were influenced by Marxism and tended to “see the racial problem in economic terms.”

Author and Professor Lawrence Patrick Jackson researched and chronicled this generation of black writers and critics and the influence of radical political associations, pan-Africanism and the “Black Bank” in Paris on the literature produced during that era. This week, we’ll take a look at his research and explore the rich legacy of The Indignant Generation.

The Chicago Black Renaissance

Although the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s has gained greater prominence, the black aesthetic movement in mid-twentieth-century Chicago also produced an influential flowering in the arts. Indeed, Chicago was the true center of The Indignant Generation.

The “Great Migration” brought tens of thousands of southern African Americans to the city, where they contributed to the development of an urban culture reflected in the visual and performing arts, literature, and music. Chicago became a pioneering center for recording and performing music. The Chicago Defender promoted black fine arts and publicized the works of artists and the institutions that supported and nurtured their creativity. The South Side Community Art Center and the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration nourished artistic creativity and organized art workshops for black citizens.

Chicago was at the center of this era between the Harlem Renaissance and the Black Arts Movement. One of the most renowned novels of the day was set in the South Side centering around the infamous protagonist, Bigger Thomas. Richard Wright’s Native Son captured the anguish, turmoil, and depths of racism during this time like no other.

The Chicago Black Renaissance literary movement emerged from broad social and cultural changes that accompanied the unprecedented expansion of the African-American community on Chicago’s South Side, beginning with the Great Migration of 1916-1918 and continuing with successive migrations throughout the 1950s that brought blacks from the Deep South to the urban North. The inception of the Chicago Black Renaissance literary movement coincides with the onset of the Great Depression of 1929 and the resulting collapse of the “Black Metropolis,” the center of the city’s African-American political, social, economic, and cultural life that developed in the 1910s around 35th and State Streets. Many blacks migrating to Chicago found that the North could be as hostile as the South, especially when it came to issues such as membership in trade unions, access to employment, and lending, insurance and housing restrictions that confined the black population to portions of the West Side and to the “Black buy viagra danmark Belt,” the overcrowded chain of neighborhoods on the city’s South Side. Their response was one of demonstrated urgency to improve conditions for their own and future generations.

By the 1930s, the Black Belt, euphemistically renamed the “Black Metropolis” existed as a narrow 40- block-long corridor running along both sides of State Street on Chicago’s South Side. African-American residential settlement was predominately confined to this enclave which was almost completely segregated. Its oldest northernmost section which encompassed the once-thriving Black Metropolis was characterized by extreme overcrowding, dilapidated tenements, high rents, and cramped “kitchenette” apartments. African-Americans fortunate enough to purchase homes often settled in the southern portions of the Black Belt or nearer the lake as they found their choices limited by discriminatory practices including housing covenants, redlining tactics, and violent protests in nearby white neighborhoods. Wide-spread unemployment, inadequate housing options, poverty, crime, and over-crowded conditions contributed to a palpable sense of frustration with the denial of citizenship rights throughout the African-American community in Chicago during the 1940s and 1950s. Despite the gravity of these problems, African-Americans promoted solidarity within their community and its institutions.

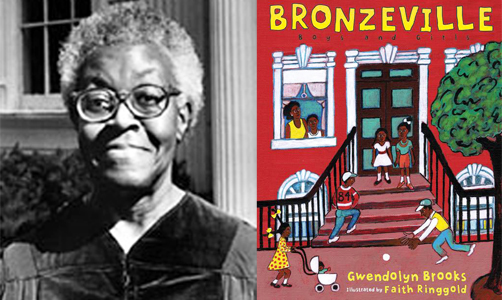

Bronzeville, one of the largest black communities in the United States, became the center of African-American culture in Chicago. Its important institutions sought to uplift the community during the 4 time by encouraging intellectual discourse and artistic expression celebrating African-American culture and a pan-African identity that sought to unify people of African descent throughout the world. Since its opening in 1932, the George Cleveland Hall Branch Library at 4801 S. Michigan Avenue

The struggle to succeed in the face of discrimination, the tension between hope and frustration, and the outrage over the escalating violence in the South are themes that anchor the novels, poems, and plays of such acclaimed Chicago Black Renaissance writers as Richard Wright, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Lorraine Hansberry (who, respectively, can be said to represent the beginning, middle, and final phases of the Chicago Black Renaissance literary movement). Through their works, the writers of the Chicago Black Renaissance literary movement gave a voice to the injustices that would culminate in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. For example, the eloquent novels and essays of internationally-acclaimed author Richard Wright were shaped, in large part, by his experiences during the years that he lived and worked in Chicago. During his time in Chicago, Wright was viewed as the galvanizing force of the Chicago Black Renaissance literary movement. In Chicago’s highly charged literary atmosphere of the 1930s and 1940s, Wright participated in the Illinois Writers’ Project of the WPA and organized the South Side Writers Group to encourage other aspiring African-American authors. Despite relocating to New York, Wright often returned to Chicago throughout the 1940s to research and lecture; maintaining a close association with the African-American cultural community in the city and mentoring emerging writers of the Black Renaissance movement. Richard Wright’s influential books, Native Son (1940), and his autobiography, Black Boy (1945), established him as one of the greatest writers of his generation and propelled him to international fame.

The lost history of the Chicago Black Renaissance