GOOD MONDAY MORNING, P.O.U.!

This weeks series is about African American Hoteliers…

JAMES WORMLEY

(1819-1884)

Wormley Hotel

Lafayette Square in the 19th century was the epicenter of political, social and civic activity in Washington, D.C. Originally the area was known as the President’s Square and just a block from the northeast corner of this common stood an establishment known as Wormley’s Hotel, probably the most successful private enterprise of its time in that area. From the humble beginnings of an African American family which had lived and worked in the White House neighborhood since the earliest years of the century, the hotel’s founder, James Wormley, developed an internationally renowned hospitality business catering to the most prominent visitors and residents of the capital.

James Wormley’s parents arrived in the District of Columbia about 1815, at which time James’s father Lynch engaged the services of the prominent lawyer Francis Scott Key to sue Smith Cocke for his certificate of freedom. Such a document was necessary at that time for any free black to be in business within the District. In those early years the Wormley family earned its livelihood from one of the only pursuits available to free blacks: personal service to the burgeoning community of white residents of Washington. Lynch and his sons were experienced horsemen and began to develop a successful livery business as hack drivers to politicians, socialites and businessmen.

Early Life of James Wormley

James, born in 1819 in the square adjacent to the west side of the park, started his business career in his youth as a jockey at the race tracks around Washington and first developed his personal skills driving the leaders of government around town in his hack. That experience exposed him to the private discussions of these men while they rode. James Wormley soon became a favorite by virtue of his skills and ability to maintain the confidentiality of private conversations as customers were driven to their destinations. Thereafter he became a steward on steamships, learning the trade of being a host and catering to the needs of his patrons.

In the early 1850s Wormley was named as the steward for the Washington Club, located in what had been the Rodgers mansion on Madison Place facing the Square. As steward of the preeminent Washington, D.C. club of its time, Wormley nurtured his relationships with the most powerful people in the city. Members of the club included the residents around and near the Square such as William Corcoran, Jefferson Davis, George Riggs and almost all of the nation’s military and public leadership. While serving as steward of the club, he also developed his own restaurant and hotel business at his houses on I St. between 15th and 16th Streets, N.W. When the club closed in 1859 the members held meetings at Wormley’s restaurant on I Street to discuss winding up the affairs of the defunct organization.

Wormley’s Famous Hospitality

As a result of Wormley’s associations with these prominent men, his services became more and more in demand. In 1860 when the first Japanese Commission was sent to Washington, Wormley was engaged to cater their sailing trip up the coast from Norfolk to Washington and then on to Philadelphia. His services must have been highly regarded, because in 1867 Secretary of State William H. Seward commissioned Wormley to have the next Japanese Commission accommodated for their entire six weeks’ stay at his houses on I Street. It was a singular honor for Wormley to have such an important delegation lodged with him, rather than at some of the larger and more commonly known hotels of the time like the Willard and the National.

Wormley’s hospitality acquired an international reputation. In his 1861 book about his travels in the United States, North America Vol. I, British novelist Anthony Trollope described his stay thusly; “I am bound to say that my friend did well for me. I found myself put up at the house of one Wormley, a colored man in I Street…I conceived myself to be greatly in luck.”

Civil War and Reconstruction

Through the Civil War years Wormley prospered. His business not only hosted military and political

leaders such as General Winfield Scott, General George McClellan and Senator Charles Sumner, his catering business was engaged to feed Confederate prisoners and late evening dinner meetings at the War Department. In May of 1862 he catered a six-day boat excursion along the eastern seaboard hosted by Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, who was joined by Secretary Seward and Attorney General Edward Bates, stopping to examine the site of the scuttled ironclad Merrimac. At the same time Wormley and his family were actively engaged in abolitionism, and his sons served on active duty in both the navy and ultimately the army.

By 1869 Wormley’s fortunes had prospered to the extent that he elected to expand his hotel business by acquiring the building at the southwest corner of 15th and H Street, N.W. By 1871 he expanded that structure by another 90 feet south along 15th Street. This building became the flagship of his enterprises, which also included the original five houses on I Street (subsequently known as Wormley’s Annex and also the Branch Hotel) and his farm with three country residences and race track on the north side of Pierce Mill Road in Tenleytown. This farm produced much of the foodstuffs used at the hotel and the track was a favorite location for the wealthy to race their horses.

The “Wormley Compromise”

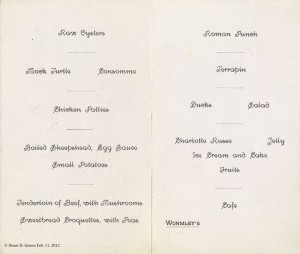

The main hotel building became one of the District’s cornerstones for politics, diplomacy and social elegance for the final decades of the 19th century. At this hotel the disputed Hayes-Tilden presidential election of 1876 was purportedly settled, coming to be known as the “Wormley Compromise.” The rooms were the residence of choice of many foreign legations from all over the Americas, Asia and Europe. In its grand dining rooms numerous private dinners were conducted wherein discussions of important matters of the day were regularly pursued. Banquets were held on a regular basis hosting presidents and their cabinets, members of Congress, justices of the Supreme Court, the military, business leaders and the diplomatic corps. These occasions were described in the nation’s newspapers as sumptuous affairs replete with large floral displays, beautiful crystal and silver services, delicious food and wines and courteous staff. In an article describing the beauty of the dinner held in honor of the marriage of the King of Spain the hotel was portrayed by the following: “On approaching Wormley’s last evening … the front entrance …an awning was arranged forming a covered way from the street to the front door. Within the hotel brilliant lights and the sounds of delicious music greeted the guests. Spacious dressing rooms for the ladies were provided in the parlors on the left of the hall, where several maids were in attendance to take care of the wrappings…The four deep broad parlors on the opposite sides were thrown together forming a magnificent salon,…”. Even the entertainment was superb, including, on occasion, the U.S. Marine Band conducted by John Phillip Sousa.

Confidante and Friend

Extending beyond the confines of the hotel and restaurants, Wormley had become the confidant, nurse and host for some of the most famous individuals of the 19th century. He was reportedly the nurse for famous men such as Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, John Calhoun, President Lincoln and family, William H. Seward, Vice President Henry Wilson and many others. After President James Garfield was shot and seriously wounded by an assassin in 1881, Wormley was retained to prepare special beef and chicken broths in an effort to nurse the suffering president back to health.

Wormley was an intimate of Frederick Douglass, John Mercer Langston, Charles Sumner and other civil rights leaders. His relationship with Sumner was so significant that Sumner gave James his personal souvenir copy of the 13th Amendment which contains over 150 original signatures. Wormley’s patrons included prominent citizens such as Louis Comfort Tiffany, John Jacob Astor, Jr., August Belmont, John Hay, Henry Adams, Henry James, Thomas Edison and others.

James Wormley died after a surgical procedure in Boston on October 18, 1884, and many of Washington’s major hotels lowered their flags to half-staff in tribute to his life. Under the leadership of his sons, the hotel continued its place at the pinnacle of Washington hospitality for another decade.

Donet D. Graves, Esq. ~ Author

(SOURCE: The White House Historical Association)

For more info, check out A Free Man of Color and His Hotel by Carol Gelderman.