GOOD MORNING, P.O.U.!

This week we’ll revisit the African American Resorts series.

IDLEWILD

Idlewild, Michigan

Idlewild is a vacation and retirement community in Yates Township, located just east of Baldwin in in southeast Lake County, a rural part of northwestern lower Michigan. During the first half of the 20th century, it was one of the few resorts in the country where African-Americans were allowed to vacation and purchase property, before such discrimination became illegal in 1964. It surrounds Idlewild Lake, and the headwaters of the Pere Marquette River run through the area. Much of the surrounding area is within Manistee National Forest.

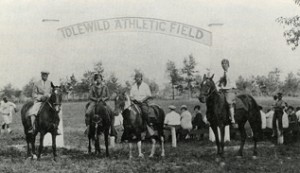

Called the “Black Eden”, from 1912 through the mid-1960s, Idlewild was an active year-round community and was visited by well-known entertainers and professionals from throughout the country. At its peak it was the most popular resort in the Midwest and as many as 25,000 would come to Idlewild in the height of the summer season to enjoy camping, swimming, boating, fishing, hunting, horseback riding, roller skating, and night-time entertainment. When the 1964 Civil Rights Act opened up other resorts to African-Americans, Idlewild’s boomtown period subsided, but the community continues to serve as a vacation destination and retirement community, and as a landmark of African-American heritage. The Idlewild African American Chamber of Commerce was founded in the summer of 2000 for the purpose of promoting existing local businesses and for attracting newer ones to the Lake County area.

Establishment (1912 – 1920s)

Idlewild was founded in 1912. During this period, a small yet clearly distinguishable African American middle class – largely composed of professionals and small business owners – had been established in many urban centers, including several in the American Midwest. Despite having the financial means for leisure travel, racial segregation prevented them from recreational pursuits in most resort destinations in the region.

(Photo: BlackPast.org/Ronald Stephens Collection)

Seeing an opportunity, four white land developers and their wives organized the Idlewild Resort Company (IRC). Erastus and Flora Branch, Adelbert and Isabelle Branch (from nearby White Cloud, Michigan), Wilbur M. and Mayme Lemon, and A.E. and Modolin Wright (of Chicago), organized IRC during the pre-World War I era. To secure land rights, Erastus Branch built a cabin, homesteaded the land for three years, and eventually obtained the title to the land through his Branch, Anderson & Tyrrell Real Estate Company, which became the central focus of the resort community.

One folk saying suggests that the community’s name refers to “idle men and wild women”. Current residents embrace this version of the story by selling playful t-shirts with this phrase at the annual Idlewilders summer festivals.

IRC organized excursions to attract middle class African American professionals from Detroit, Chicago, and other Midwestern cities, taking them on tours of the rustic community, and selling lots. A 1919 pamphlet used by IRC to promote the community, entitled “Beautiful Idlewild”, describes it as “the hunter’s paradise” renowned “for its beautiful lakes of pure spring water” and “its myriads of game fish”. One prominent personality to relocate to Idlewild was Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, who in 1893 was the first surgeon in the United States to perform open-heart surgery. Williams, Herman O. and Lela G. Wilson of Chicago, three of Williams’ associates from Chicago and Cleveland, and twenty others were among the first group of African American professionals to join IRC’s excursion. Later, tours were conducted by train from Chicago, Indiana, Detroit, Grand Rapids, St. Louis, and other cities.

IRC had acquired over 2,700 acres (11 km2) of land. The company sold a good deal of that land, and then turned the island in Idlewild Lake over to Williams and Louis B. Anderson of Chicago, and Robert Riffe and William Green of Cleveland, who collaboratively formed the Idlewild Improvement Association (IIA) and helped build the clubhouse. IIA sold property to such notables as NAACP co-founder W.E.B. Du Bois, cosmetic entrepreneur Madam C.J. Walker, Fisk University president Lemuel L. Foster, Albert B. Cleage Sr. of Detroit, Fannie Emanuel of Chicago, and novelist Charles Waddell Chesnutt.

IIA was also responsible for recruiting other middle-class  professionals, such as NAACP field secretary William Pickens, H. Franklin and Virginia Bray (a missionary and his wife who together founded the first formal church in Idlewild), and the Reverend Robert L. Bradby, Sr. of Second Baptist Church of Detroit (who contributed to the development of the Idlewild Lot Owners Association). IIA encouraged this new influx of community leaders to foster racial pride, economic development, decency, and respect to Idlewild.

professionals, such as NAACP field secretary William Pickens, H. Franklin and Virginia Bray (a missionary and his wife who together founded the first formal church in Idlewild), and the Reverend Robert L. Bradby, Sr. of Second Baptist Church of Detroit (who contributed to the development of the Idlewild Lot Owners Association). IIA encouraged this new influx of community leaders to foster racial pride, economic development, decency, and respect to Idlewild.

The annual Idlewild Chautauqua was organized by Reverend buy viagra netherlands Bradby. These week-long events added an intellectual favor to the recreational life in the community, attracted people from across the country, and were praised by Michigan Republican Governor Fred W. Green.

The height of popularity (1920s – 1964)

Idlewild became known as the “Black Eden of Michigan”. As this new black intelligentsia began to settle in the community, some relocated as activists and members of Marcus Mosiah Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), some as followers of Du Bois’ National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), others as believers of the late Booker T. Washington’s political machine, and others as potential investors. For the majority of these professionals who brought their families, the idea of land ownership conveyed black social status and membership in this community.

Idlewild gained national stature among African Americans during the period between the World Wars. For example, the Idlewild Land Owners Association had members from over thirty-four states in the country. In addition, the Purple Palace, Paradise Clubhouse, Idlewild Clubhouse, Rosanna Tavern, and Pearl’s Bar provided summer entertainment for tourists and employment opportunities for seasonal and year-round residents in the community. The Pere Marquette Railroad built a branch line to the area by 1923. A post office opened that same year. The Idlewild Fire Department was established, and a host of new entrepreneurs began entering the community. Paradise Palace became McKnight’s Convalescent Home.

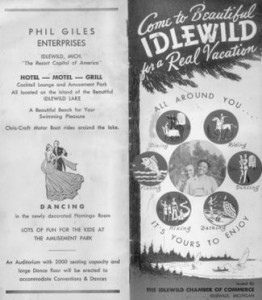

Following World War II, Idlewild attracted what some sociologists have labeled the new African American “working” middle class. With the construction of a few paved roads in Idlewild, a reinvestment in the township’s only post office, and greater availability of electricity, a new generation of entrepreneurs began to invest in Idlewild. Phil Giles, Arthur “Big Daddy” Braggs, and a host of other African American businessmen and women took advantage of the market by purchasing property on Williams Island and Paradise Gardens, and began developing these areas into an elaborate nightspot and business center. The cottage started by Albert Cleage in the 1940s was expanded by his sons Louis, Hugh, and Henry.

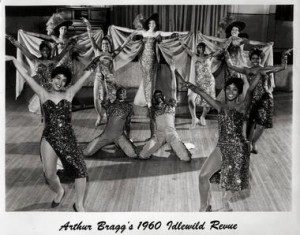

Many African American entertainers of the period performed in Idlewild. Della Reese, Al Hibbler, Bill Doggett, Jackie Wilson, T-Bone Walker, George Kirby, The Four Tops, Roy Hamilton, Brook Benton, Choker Campbell, Lottie “the Body” Graves, the Rhythm Kings, Sarah Vaughan, Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong, Dinah Washington, B.B. King, Aretha Franklin, Fats Waller, and Billy Eckstein, and many other performers, entertained both Idlewilders and white citizens in neighboring Lake County townships throughout the 1950s and early 1960s. Arthur Braggs produced singers, dancers, showgirls, and entertainers, which helped Idlewild to become the “Summer Apollo of Michigan”. Braggs produced the famous “Arthur Braggs Idlewild Revue” which not only performed in Idlewild but was also taken on the road to Montreal, Boston, Kansas City, Chicago, New York, and other cities. Braggs’ show helped Idlewild become a major entertainment center and contributed to the financial prosperity of the area.

Decline and redevelopment efforts (1964 – present)

Following the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, business in Idlewild declined. Other vacation resorts were beginning to accommodate African American visitors, and with federal law requiring that they be accepted anywhere, African Americans began taking advantage of this opportunity. The national recession in the early 1970s further contributed to an economic downturn in Idlewild, which led to a population decline as local employment options dwindled. Idlewild became a lesser-known family vacation and retirement community, primarily attracting retirees who remembered it from its boom period.

In the 1970s township officials organized a planning commission, zoning board, and other initiatives as a way to encourage community input and to offer specific practical solutions to improve the community. Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) were obtained for demolition, additional roadwork, and other structural changes, which resulted in a complete makeover of the island, renamed “Williams Island” in honor of early community leader Dr. Daniel Hale Williams. In the 1990s, with federal and state funding scarce, attention was turned away from building projects toward the renovation of existing township properties. The federal government designated Lake County as an “Enterprising Community”, which facilitated the development of sewer and natural gas systems. Businessman John O. Meeks purchased and renovated the Morton Motel, and founded organizations to develop and promote the community, including Mid-Michigan Idlewilders and the Idlewild African American Chamber of Commerce.

The National Idlewilders Club continues to organize annual events, including the Idlewild Jazz Festival. The National Idlewilders consists of local chapters in six cities, and Idlewild Lot Owners Association has local chapters in eight cities. Attendance at the annual summer festivals has steadily increased since 2000.

(SOURCE: Wikipedia)